Influenza in pregnancy poses significant risks to pregnant women and their babies. In 2009, there were four maternal deaths due to influenza in New Zealand.1 Influenza is a potentially preventable disease with free vaccination available to pregnant women in Australia and New Zealand. In New Zealand there is a vocal anti-vaccination lobby and as health professionals it is our role not only to understand the disease process, understand the vulnerability of pregnant women and know how to recognise, diagnose and treat influenza but also to promote vaccination and enable women to easily access it.

Long ago

One hundred years ago, the Spanish Flu spread throughout the world. Commonly referred to as the black flu due to the bodies becoming so cyanosed, they would turn black upon death. It resulted in the deaths of nearly 60 million people, three times that of World War I.2

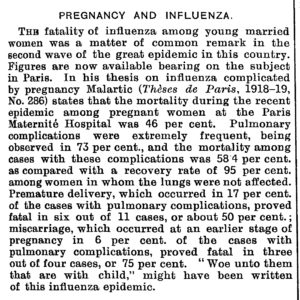

In the October of 1919, Marlartic reported in the Lancet on the maternity experience in Paris. Influenza in pregnant married women had resulted in a 46 per cent maternal mortality. In the 73 per cent of women that had pulmonary complications, 17 per cent resulted in premature delivery, with a perinatal mortality rate of 50 per cent. Simply summarised, ‘Woe unto them that are with child’.3

This was the first recognition that influenza complicated by pregnancy carried extra risk for mother and child.

Figure 1. Excerpt from Lancet, 1919.

Not so long ago

Ten years ago, in 2009, the H1N1 influenza spread throughout the world, requiring the World Health Organization to announce a maximum, level 6, Global Pandemic Alert.4

Data collected during this period furthered the knowledge that pregnant women were at increased risk of complications from influenza.

Pregnant women were three times more likely to be hospitalised than the general population and they accounted for 5 per cent of deaths, despite only representing 1 per cent of the population.5 Maternal mortality was estimated at 6.9 deaths per 100 000 maternities in New Zealand and Australia during this time.6

Babies of the mothers who were severely affected had an increased risk of fetal growth restriction, spontaneous abortion, preterm delivery and subsequent perinatal mortality.7

Prior to 2009, serious concern for pregnant women with influenza, was only considered if they also had another risk factor such as asthma, smoking, obesity or diabetes. After 2009, it was now recognised that pregnancy alone is a significant risk factor and prompt treatment should be initiated for all.8

Data collected during this period also showed pregnant women of Aboriginal, Torres Strait Islander, Māori and Pacific descent are at higher risk.9

Current day

New Zealand and Australia continue to see high numbers of pregnant women admitted to ICU with seasonal influenza during the months of May to October each year.

Complications include pneumonia, renal failure and encephalopathy, requiring admission to intensive care units (ICU), intubation and occasionally even extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Their ICU stays are usually longer than non-pregnant women and preterm surgical deliveries are performed to relieve the systemic burden and aid recovery.10

Increased risk to pregnant women

All medical personnel involved with the care of pregnant women need to be aware of the risk of influenza to all pregnant women.

The reason influenza is more severe in pregnancy is likely due to a combination of the immunological shift from a cell-mediated response to an antibody-mediated one and physiological cardiorespiratory changes (such as reduced functional residual capacity), which worsens throughout pregnancy.11

Given the length of the influenza season and that there is risk at all stages of pregnancy, these messages are relevant to every pregnancy.

Box 1. Increased risk of influenza in pregnancy.

- Pregnant women are at higher risk of hospitalisation from influenza

- Pregnant women with comorbidities such as asthma, diabetes and obesity are at further increased risk

of complications - Aboriginal, Torres Strait Islanders, Māori, and Pacific Islanders are at further increased risk of complications

- Influenza in pregnancy complicated by pneumonia is associated with significant risk to both mother

and fetus - Complications from influenza increases with gestation and continues into the postpartum period

- Maternal hyperthermia is associated with congenital anomalies, but can be mitigated by antipyretics

- Influenza does not cross the placenta

Safety and effectiveness of vaccination

Vaccination is well established to be safe and effective in pregnancy.12 Pregnant women in Australia who received an influenza vaccination in 2012 were 81 per cent less likely to attend an emergency department with an acute respiratory infection, and 65 per cent less likely to be hospitalised.

Most convincing may be the fact that maternal vaccination allows transplacental transfer of IgG, giving the newborn immunological protection for the first six months of life, at a time when they are too young to be immunised.

‘Not only for themselves, but also for their unborn child’. M Knight.13

Unfortunately, vaccination rates in Australia and New Zealand continue to be poor (Table 1).

Table 1. Influenza vaccination rates in pregnancy.

| Influenza vaccination rates in pregnancy | |

| USA (2017–2018) | 49.1% |

| England (2016–2017)

England (2017–2018) |

44.9%

47.2% |

| South Korea (2014) | 37.8% |

| Australia (Vic 2015–2017)9 | 39% |

| New Zealand | Not reported |

Influenza vaccination is free to all pregnant women in New Zealand and Australia, but the usual barriers to healthcare still exist (lack of awareness, information, time, language barriers or lack of adequate counselling).

In 2016, Waitakere Hospital, NZ, a vaccinator was situated in antenatal clinic. This significantly increased immunisation rates demonstrating that pregnant women are excepting of vaccination if given the opportunity. Obstetric departments should campaign to their managers to provide funding for an opportunistic vaccinator to be in antenatal clinic during these months of the year, as prevention is truly the best option.

The cost-benefit has been estimated to prevent one to two hospitalisations per 1000 women vaccinated during the second or third trimester.14

Box 2. Transmission of influenza.

Influenza

Contagious viral respiratory tract infection

Method of spread

Droplets and surface contamination

Incubation period

1–7 days (usually 1–3 days)

Infectious period

1 day prior to symptoms

until day 5 in adults

until day 7 in children (note: can be until day 21)

Safety and benefit of the use of antiviral treatment

Hospitalised pregnant women who receive a neuraminidase inhibitor within the first two days of onset of symptoms had 84 per cent reduction in ICU admission and were one fifth as likely to die than women who were treated later or not at all.15

Box 3. Influenza vaccination in pregnancy.

Influenza vaccine:

- Can be given at any gestation of pregnancy

- Takes 2 weeks to begin to be effective

- Is, at best, only 60% effective – if a woman has symptoms of influenza, she should present to a doctor, even if she has been vaccinated

- Gives immune benefit to the newborn for the first six months of life

General advice

Hand hygiene and cough etiquette should be reiterated. Breastfeeding should be encouraged given the immunological benefits passed on from the mother in her milk.

Box 4. Antivirals for influenza in pregnancy.

Neuraminidase inhibitors:

- Are safe in pregnancy

- Should be started before/despite lab results

- Are most effective in pregnancy when started within 48 hours of symptoms starting

- Still have benefit when given after 48 hours, therefore should be started anyway

- Should be given to women with influenza symptoms, even if she has been vaccinated, as vaccination is only 60% effective

- Will benefit women up to two weeks postpartum

- Has very low placental transfer of 1–14% of maternal concentration

- Rx: Oseltamivir 75 mg BD for five days

Call to action

Let us not be idle. We now live in a time where women are more frequently accessing medical advice from online social sources than from a health professional. We need to go to women with the health messages they need.

We need to get social media savvy; use our Twitter accounts, practice’s website and Facebook pages and share when the flu season has begun and the benefits of vaccination.

Prevention is where we are going to win the fight with influenza in pregnancy, and education of the public is how we are going to achieve it.

References

- PMMRC. 2012. Sixth Annual Report of the Perinatal and Maternal Mortality Review Committee: Reporting mortality 2010. Wellington: Health Quality & Safety Commission. Available from: www.hqsc.govt.nz/assets/PMMRC/Publications/PMMRC-6th-Report-2010-Lkd.pdf.

- Rice G. ‘That Terrible Time’ : Reflections on the 1918 Influenza Pandemic in New Zealand. NZMJ. 2018;131(1481):6-8.

- PREGNANCY AND INFLUENZA. Lancet. 1919;194(5016):699.

- Rasmussen SA, Jamieson DJ. 2009 H1N1 Influenza and Pregnancy — 5 Years Later. NEMJ. 2014;371(15):1373-5.

- Rasmussen SA, Jamieson DJ. Influenza and pregnancy in the United States: before, during, and after 2009 H1N1. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2012;55:487-97.

- Knight M, Pierce M, Seppelt I, et al. Critical Illness with AH1N1v Influenza in Pregnancy: A Comparison of Two Population-based Cohorts. BJOG. 2011;118(2)232-9.

- Rasmussen SA, Jamieson DJ. Influenza and pregnancy in the United States: before, during, and after 2009 H1N1. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2012;55:487-97.

- Rasmussen SA, Jamieson DJ. Influenza and pregnancy in the United States: before, during, and after 2009 H1N1. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2012;55:487-97.

- Kelly H, Mercer GN, Cheng AC. Quantifying the Risk of Pandemic Influenza in Pregnancy and Indigenous People in Australia in 2009. Euro Surveillance: Bulletin. 2009;14(50):6-8.

- Knight M, Pierce M, Seppelt I, et al. Critical Illness with AH1N1v Influenza in Pregnancy: A Comparison of Two Population-based Cohorts. BJOG. 2011;118(2)232-9.

- Mighty HE. Acute respiratory failure in pregnancy. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2010;53:360-8.

- Influenza vaccination during pregnancy (and in women planning pregnancy). (C-Obs 45) RANZCOG Statements 2017. Available from: ranzcog.edu.au/statements-guidelines/obstetrics/influenza-vaccination-during-pregnancy-(c-obs-45)

- Knight M, Pierce M, Seppelt I, et al. Critical Illness with AH1N1v Influenza in Pregnancy: A Comparison of Two Population-based Cohorts. BJOG. 2011;118(2)232-9.

- Australian Government. The Australian Immunisation Handbook: 10th Edition. Canberra, 2013. Available from: immunisationhandbook.health.gov.au.

- Yates L, Pierce M, Stephens S, et al. Influenza A/H1N1v in Pregnancy: An Investigation of the Characteristics and Management of Affected Women and the Relationship to Pregnancy Outcomes for Mother and Infant. Health Technology Assessment. 2010;14(34):109-82.

Leave a Reply