Setthathirath Hospital is one of the university teaching hospitals in Vientiane, and the only one with a gynaecologic oncology unit. We receive tertiary referral patients from around the country and from the other central hospitals. In the last calendar year, we performed 196 elective gynaecological laparotomies, for 121 of which we used a Maylard incision, while the rest had vertical incisions. We started using Maylard incisions exclusively for elective gynaecological surgery (except in cases where a midline incision was clearly indicated) in December 2010, so we have extensive experience with the technique.

Maylard described his incision in 1907: he appreciated the benefits of transverse incisions, particularly their low dehiscence rates, but wanted better exposure, especially of the pelvic side walls. This exposure is extremely valuable for more complex cases, but enables safer surgery in all cases. In our cancer surgery, we use the Maylard incision for endometrial cancer procedures involving pelvic lymphadenectomies, but not for ovarian or cervical cancer.

Basic anatomy

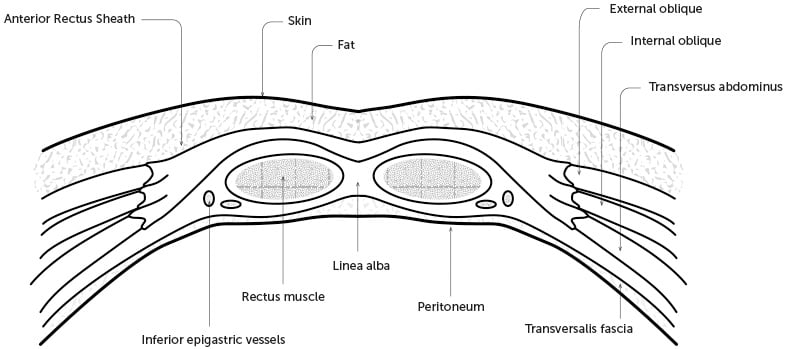

The anterior abdominal wall below the umbilicus

The lateral part of the muscular abdominal wall on either side is made up of a layer of three muscles; the external oblique most superficially, overlying the internal oblique beneath which is the transversus abdominus. The tendons of these three muscles fuse at the lateral border of the rectus abdominus, which is a strap-like muscle running from the symphysis pubis inferiorly to the costal margins superiorly. The fused tendons of the lateral muscles form a sheath to surround the rectus muscles, fusing in the midline linea alba. Above the so-called arcuate line the sheath completely surrounds the rectus muscles, but below the arcuate line the posterior sheath is absent, replaced by the transversalis fascia, deep to which is peritoneum.

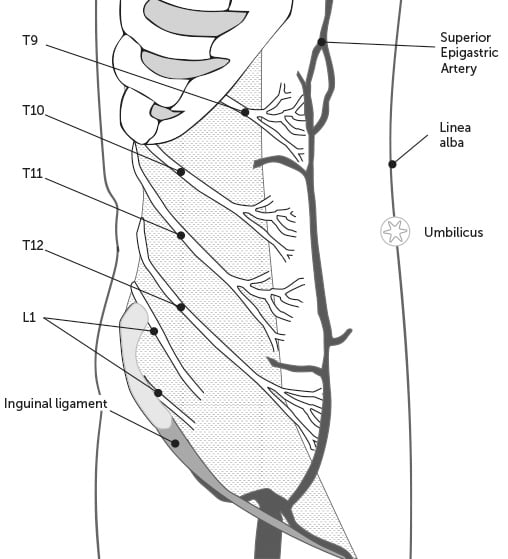

The inferior epigastric artery and vein

The artery arises from the external iliac artery, exits the abdomen through the inguinal canal and runs beneath the rectus abdominus in the rectus sheath, supplying the muscle with blood, anastomosing with the superior epigastric artery, which is the terminating portion of the internal thoracic artery, around the umbilicus. The artery is accompanied by a vein.

Potential nerve damage

With any transverse lower abdominal incision, there is the possibility of damage to spinal nerves that pass through the transversalis muscle as they curve forward and inferiorly from their origin in the spinal canal. The nerves most likely to be damaged are the iliohypogastric and ilioinguinal nerves, both branches of L1. This will usually only happen where the incision extends some distance into the fascia and muscles several centimetres beyond the rectus sheath. The symptoms vary, from paraesthesia to severe and intractable pain in the distribution of the nerve and is treated by either neurolysis or division of the nerves as they exit the fascia. We have not incurred this problem in our experience of more than 1000 consecutive cases, but have seen it in cases of repeat Pfannenstiel incisions, especially when surgery was difficult.

Figure 1. A cross section of the abdominal wall below the arcuate line

Technique

Incision site

We examine every patient under anaesthesia before making a final decision as to whether a transverse or vertical incision is most appropriate. We take particular note of the size and mobility of the uterus and the presence of adnexal masses. In general, a Maylard incision is best done a little higher than a Pfannenstiel, but the exact site will vary depending on the examination findings. Where the cervix is large or the uterus relatively immobile, the incision needs to be low enough to allow good access to the cervix.

Steps in the procedure

We use a straight incision about 2–3 cm above the symphysis pubis. A scalpel is used to incise the skin to the upper level of subcutaneous fat. Electrocautery is used to incise subcutaneous fat in the midline down to the anterior rectus sheath. Two small incisions in the sheath are made, one on each side of the midline. A large clamp is inserted beneath the sheath and above the rectus muscle and the fat and fascia divided to the lateral margin of the rectus on each side.

The clamp is then inserted beneath the rectus muscle, from the lateral to the medial border, running along the surface of the transversalis fascia. It is pushed through the rectus muscle about 1 cm from the midline. We deliberately avoid the midline at this stage. One corner of a clean dry surgical pack is inserted into the open jaws of the clamp and pulled back under the rectus muscle, exiting laterally. This pack is used to lift the rectus muscle from the transversalis fascia, reducing the risk of inadvertent damage to deeper structures. Electrocautery is used to divide the rectus in smooth strokes, beginning medially. No attempt is made to control small bleeders in the muscle. As the incisions in the muscle go deeper, care is taken to identify the inferior epigastric vessels, which are usually above the pack. They are typically together and have a small amount of fat surrounding them. When they are located, the surrounding muscle is carefully incised to allow the vessels to be clamped, divided and tied. In some cases, the inferior epigastric vessels will be left on the transversalis fascia at the lateral edge of the rectus sheath after the rectus muscles are divided. If that is the case, they are carefully elevated with artery clamps, clamped, divided and tied.

We believe the inferior epigastric vessels should be divided in every case to reduce the risk of inadvertent laceration or tearing during the operation or at wound closure.

Next, the transversalis fascia and underlying peritoneum on the right-hand side are grasped and elevated with artery forceps and the abdominal cavity opened. The right-hand side is chosen because, in general, adhesions are less common than on the left, though this may not be the case after appendicectomy. Under vision, and with the abdominal wall elevated with fingers, the transversalis fascia and peritoneum are incised toward the midline using electrocautery. When the lateral edge of the remaining rectus muscle is reached, the peritoneum and the layers above are divided to the linea alba and then on through the remnants of the left rectus muscle, together with the peritoneum, to the left-hand extent of the incision.

Occasionally, there will be bleeding from this central area, but it is easily controlled by electrocautery.

The peritoneum in the midline superiorly and inferiorly are sewn to the edge of the skin. In obese women, the peritoneum at the lateral ends of the incision can also be sewn to the skin to facilitate placement of a retractor.

On occasion, there will be bleeding from the belly of the rectus muscle after it has been divided. We make no attempt to secure the particular vessels, but rather place a large mattress suture through the fascia, muscle and peritoneum about 1 cm above the cut edges, taking it across the peritoneum about 1 cm and then passing it through peritoneum, muscle and fascia and tying it firmly on the fascial surface. The suture should be tight enough to stop the bleeding, but not so tight as to strangulate it and cause muscle necrosis.

The same technique can be used if the inferior epigastric vessels retract before they can be clamped.

We do not drain the wound and have had no haematomas in our extensive experience.

Figure 2. The main nerves supplying the anterior abdominal wall, and the course of the inferior and superior epigastric vessels in the rectus sheath.

Wound closure

The peritoneum and transversalis fascia are closed with a running suture of braided synthetic material. No attempt is made to secure the cut edges of the muscle to the fascia. The muscle adheres firmly to the sheath unless it is purposely freed.

We close the fascia with a continuous suture of number one, braided synthetic absorbable suture, running from one end to the other. If needed, a few fat sutures are inserted, and the skin closed with a subcuticular suture.

Other issues

Pain with a Maylard incision

Several authors assert that Maylard incisions produce more postoperative pain than Pfannenstiel incisions, but the evidence is the opposite, with a number of studies demonstrating either no greater pain or less pain with the Maylard incision. We believe this is because, apart from the incision of the muscles, there is minimal tissue disruption within the rectus sheath such as occasioned by stripping the rectus from its sheath to gain exposure in a Pfannenstiel incision.

Enlarging the incision

Exposure to the lower part of the abdominal cavity is excellent with this incision. On a number of occasions, the finding of unexpected upper abdominal disease has necessitated enlargement of the incision. We do this by dividing the fused tendons of the muscles lateral to the rectus sheath vertically, lateral to, and parallel with, the rectus sheath. Usually, no further skin incision is needed. We have performed hemicolectomies and even a splenectomy through these enlarged Maylard incisions. The fascia is closed with a running suture through to the peritoneum, running inferiorly to the lateral edge of the original incision of the rectus sheath, and the wound closed in the usual way.

Conclusion

The Maylard incision has been extremely effective in facilitating safe gynaecological surgery in Setthathirath Hospital. Although it takes a little longer than the Pfannenstiel incision, our operating times for simple hysterectomies are one hour or less. More complex surgery is both easier and safer with the improved exposure afforded by the incision. We believe there are compelling reasons for the use of this technique where a transverse incision is indicated in gynaecological surgery.

References

- Chaywiriyangkool C, Manusook S, Pongrojpaw D, et al. Comparative Study of Postoperative Pain between Maylard Incision and Pfannenstiel Incision in Gynecologic Surgery: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Med Assoc Thai. 2016;99 Suppl 4:S16-22.

- Helhamp B, Krebs HB. The Maylard incision in gynecologic surgery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990;163(5):1554-7

- Ghanbari Z Baratali BH, Foroughifar T, et al. Pfannenstiel versus Maylard incision for gynecologic surgery: a randomized, double-blind controlled trial. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;48(2):120-3.

- Giacalone PL, Daures JP, Vignal J, et al. Pfannenstiel versus Maylard incision for cesarean delivery: A randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;99:745-50.

Leave a Reply