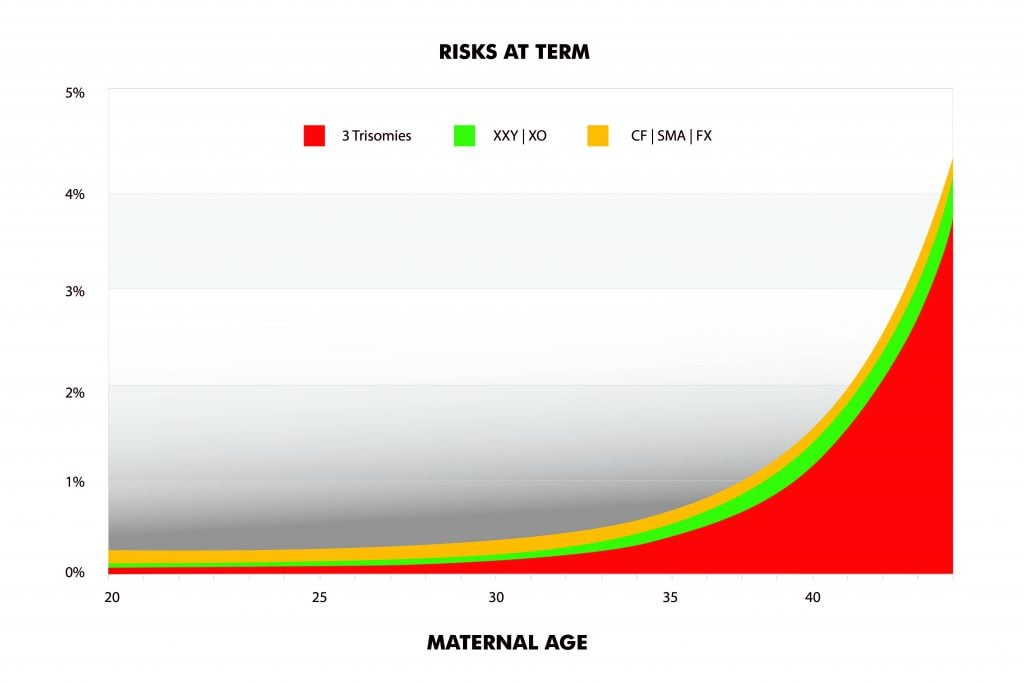

Antenatal screening for chromosome disorders is an established part of reproductive care in Australia. Although the combined risk of chromosome abnormalities rises markedly with maternal age (Figure 1), younger mothers have more babies than older mothers, and the overall outcome is that the majority of pregnancies with a chromosome disorder occur in mothers under 35 years of age. For this reason, screening for chromosome disorders in pregnancy should be offered to mothers, irrespective of maternal age.

The great majority of these chromosome disorders are new abnormalities that have occurred after conception. These are not inherited disorders and genetic testing of the parents would provide little indication of the risk of a chromosome abnormality. For this reason, screening for chromosome disorders in pregnancy should be offered to all mothers, irrespective of family history.

Universal antenatal screening for recessive genetic disorders

Chromosome disorders are not the only type of genetic condition that can affect the developing fetus. Many serious childhood disorders are due to recessive mutations that have been inherited from parents, with the parents being unaffected by these mutations. A parent who is a carrier of a recessive mutation on an autosome, that is, chromosomes 1-22, has one normal and one abnormal copy of a gene, and will not usually be affected by the abnormal gene. Everyone is a carrier for one or more recessive disorders; this is of no immediate consequence and there is usually no family history of the disorder.

The situation changes if both parents are carriers of mutations in the same autosomal gene. The chance of their child inheriting the abnormal gene from each parent, and so developing an autosomal recessive disorder, is 25 per cent. The situation is similar for a woman with a recessive mutation on one of her X-chromosomes: each of her sons is at 50 per cent risk of inheriting the abnormal gene and being affected, and half of her daughters will be carriers. Overall, the risk of a woman who is an X-linked carrier having an affected child is approximately 25 per cent.

The risk of a recessive disorder does not vary with maternal age and, although the mutations are inherited, there is usually no family history to provide a clue of this risk. For mothers under 30 years of age, the risk of having a child with any one of just three common disorders (cystic fibrosis, spinal muscular atrophy or fragile X syndrome) is greater than the risk of having a child with one of the autosomal trisomies, Turner syndrome (45,X) or Klinefelter syndrome (47,XXY) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Risks of different genetic disorders at term.

This presents an opportunity to move beyond antenatal screening for chromosome disorders, and to begin tackling the risk of recessive disorders. While screening for recessive disorders raises some issues that are very different from screening for chromosome abnormalities, there are two crucial points at which the principle is the same:

- Reproductive carrier screening should be offered to all mothers, irrespective of age and family history. This is reflected in the recent RANZCOG Statement on prenatal screening for genetic conditions (see Box 1).

- A woman is free to accept or decline carrier screening, and is free to use or ignore the information provided by the test. The goal of antenatal screening, whether it be for chromosome or recessive disorders, is to allow the patient to make her own informed choices.

Recommendation 15

Information on carrier screening for the more common genetic conditions that affect children (e.g. cystic fibrosis, spinal muscular atrophy, fragile X syndrome) should be offered to all women planning a pregnancy or in the first trimester of pregnancy.

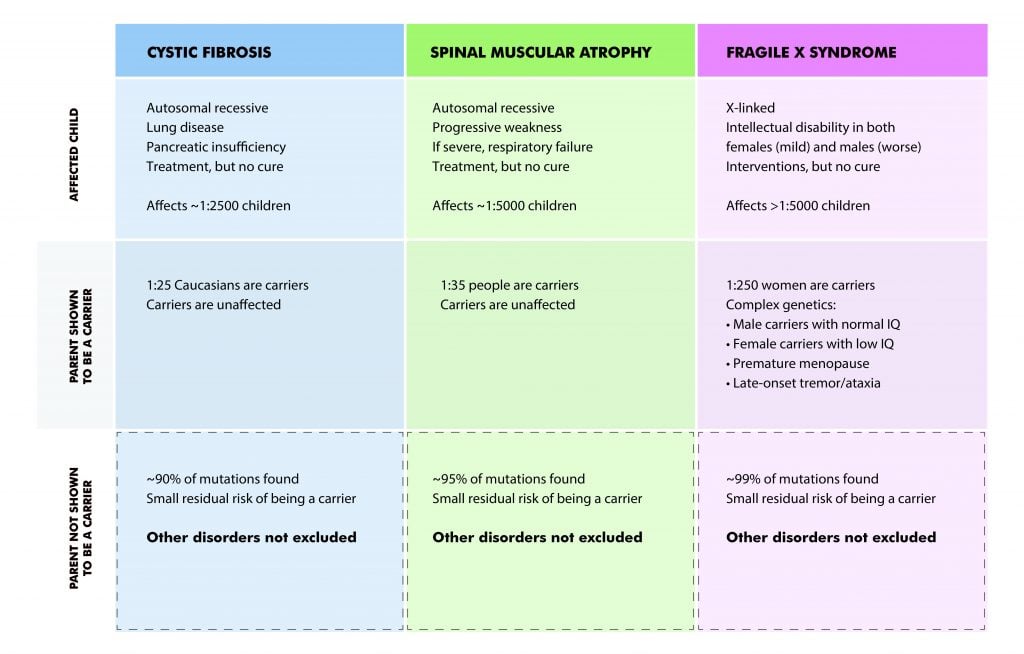

Clinical features of cystic fibrosis, spinal muscular atrophy and fragile X syndrome

Approximately six per cent of people are carriers of one or more of these conditions and 0.6 per cent (one in 160 couples) are at 25 per cent risk of having an affected child. A summary of these disorders is shown in Figure 2. The three conditions carry serious consequences for the affected child, whether that be in terms of life-long respiratory compromise, limited lifespan or intellectual disability. In general, those shown to be carriers of these disorders are unaffected, with the key proviso that carriers of the fragile X mutation can develop ovarian failure or a neurodegenerative disorder in adult life. Those who are not identified as carriers may still be at risk, albeit very low risk, of being carriers due to an undetected mutation.

Figure 2. Summary of clinical and genetic features of three common recessive disorders.

Managing reproductive carrier screening

Testing for mutations in the parents presents both an opportunity and a challenge. There is an opportunity to test prior to pregnancy. This is by far the best time for the test to be done, as it gives the couple time to review the result and make informed reproductive choices. A couple who is shown to be at 25 per cent risk of having an affected child can consider the use of donor egg or sperm (as appropriate), pre-implantation genetic diagnosis or prenatal diagnosis, or they may simply accept the risk that has now been clarified.

The challenge is that many women do not seek medical advice until they are pregnant. Pregnancy provides a convenient trigger to raise the matter of carrier screening, but it leaves little time for considered reflection of the results and the pre-conception options are no longer available. A couple who is shown to be at high risk of having an affected child can, within a limited time frame, consider prenatal diagnosis, or they may simply accept the risk that has now been clarified.

General practitioners are best placed to identify women who may be planning a pregnancy and to raise the possibility of reproductive carrier screening. Obstetricians may be able to raise the issue with women within the first trimester, recognising that the window of opportunity to clarify carrier status of the partner and arrange prenatal testing is closing rapidly. However, obstetricians are uniquely well placed to raise the issue postnatally, offering the couple the opportunity for carrier screening prior to their next pregnancy. Reproductive carrier screening need only be done once, but there is no need for it to be restricted to a couple’s first pregnancy.

Carrier screening can be done sequentially or simultaneously. Sequential testing refers to testing the woman first, and only testing her reproductive partner if she is identified as a carrier of an autosomal recessive disorder. This has the advantage of being cheaper (on average), but slows the process because the partner must be recalled for testing. This may not be a major issue if the couple are having pre-pregnancy testing.

Simultaneous testing involves both partners at the same time. This has the advantage of speed, but it is a more expensive process. This may be acceptable for couples who want a prompt result, for example, for those who are already pregnant.

Reproductive carrier screening does not replace long-established recommendations, such as taking a family history and reviewing a blood count for evidence of thalassaemia carrier status. If there is a family history of a genetic disorder, the couple should be referred for genetic counselling and tested specifically for that disorder, as the key mutation may not be detected by a screening program.

Genetic counselling

Some providers offer free genetic counselling for couples identified as being at high risk of having an affected child. Services can also be accessed through public and private providers nationally (www.hgsa.org.au/asgc/find-a-genetic-counsellor and www.sonicgenetics.com.au/counsellingservices, respectively).

Expanded reproductive carrier screening

There are hundreds of inherited autosomal and X-linked recessive disorders that present in infancy and early childhood. These disorders are individually rare, but together, they are more common than the combined impact of chromosome disorders and the three common disorders already mentioned. Until recently, the only way of identifying carriers of rare recessive disorders was in hindsight, after diagnosing a recessive disorder in their affected children. This has now changed. It is possible to screen a couple for recessive mutations in hundreds of autosomal and X-linked genes. This screening test is called expanded carrier screening. The performance of different expanded carrier screening panels varies, with up to 70 per cent of individuals being identified as carriers, and up to three per cent of couples being shown to be at high risk of having an affected child.

The cost of reproductive carrier screening

The cost of a three-gene panel screening for cystic fibrosis, spinal muscular atrophy and fragile X syndrome is A$350–400 per person. There is no Medicare rebate. However, there are exceptions (and restrictions) for people with a documented family history of a specific mutation causing cystic fibrosis or the fragile X syndrome.

The cost of expanded carrier screening ranges from a few hundred dollars to more than $1000. This cost is not rebated by Medicare. The Australian Federal Government is currently funding a trial of expanded carrier screening, Mackenzie’s Mission, to determine the cost and benefit of providing this screening as a national funded program.

Conclusion

It is accepted practice that every woman is offered screening for chromosome disorders in pregnancy, irrespective of age and family history. Every couple should also be offered reproductive carrier screening for recessive disorders, irrespective of age and family history. For younger mothers, the risk of their child having a recessive disorder is greater than the risk of a chromosome disorder. Offering reproductive carrier screening simply represents good medical practice.

References

- Archibald AD, Smith MJ, Burgess T, et al. Reproductive genetic carrier screening for cystic fibrosis, fragile X syndrome, and spinal muscular atrophy in Australia: outcomes of 12,000 tests. Genet Med. 2017;20(5):513-523.

- Edwards JG, Feldman G, Goldberg J, et al. Expanded carrier screening in reproductive medicine – points to consider. Obs Gynecol. 2015 Mar;125(3):653-62.

- RANZCOG. Prenatal screening and diagnostic testing for fetal chromosomal and genetic conditions. August 2018.

- Romero S, Rink B, Biggio JR, Saller DN. Carrier screening in the age of genomic medicine. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129(3):35-40.

Conflict of interest

Prof Suthers is an employee of Sonic Healthcare, who provide reproductive carrier screening tests for the three common disorders and an expanded screen for over 300 disorders.

Leave a Reply