Gestational trophoblastic disease (GTD) is a group of placental disorders derived from a pregnancy1 consisting of abnormal proliferation of trophoblastic tissue of the placenta. GTD covers benign partial and complete hydatidiform mole, invasive mole, gestational choriocarcinoma, placental site trophoblastic tumour, and epithelioid trophoblastic tumour.2 Gestational trophoblastic neoplasia (GTN) is GTD with the requirement of chemotherapy and/or excisional treatment due to persistence of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) or presence of metastases.3 Choriocarcinoma is the most common GTN and often follows a molar pregnancy.4

Case

A 38-year-old Tongan woman presented at six weeks gestation with a two-day history of vaginal bleeding.

In 2012, she had a complete molar pregnancy followed by persistent disease and was treated with six months of methotrexate and actinomycin-D chemotherapy, after which she was lost to follow-up.

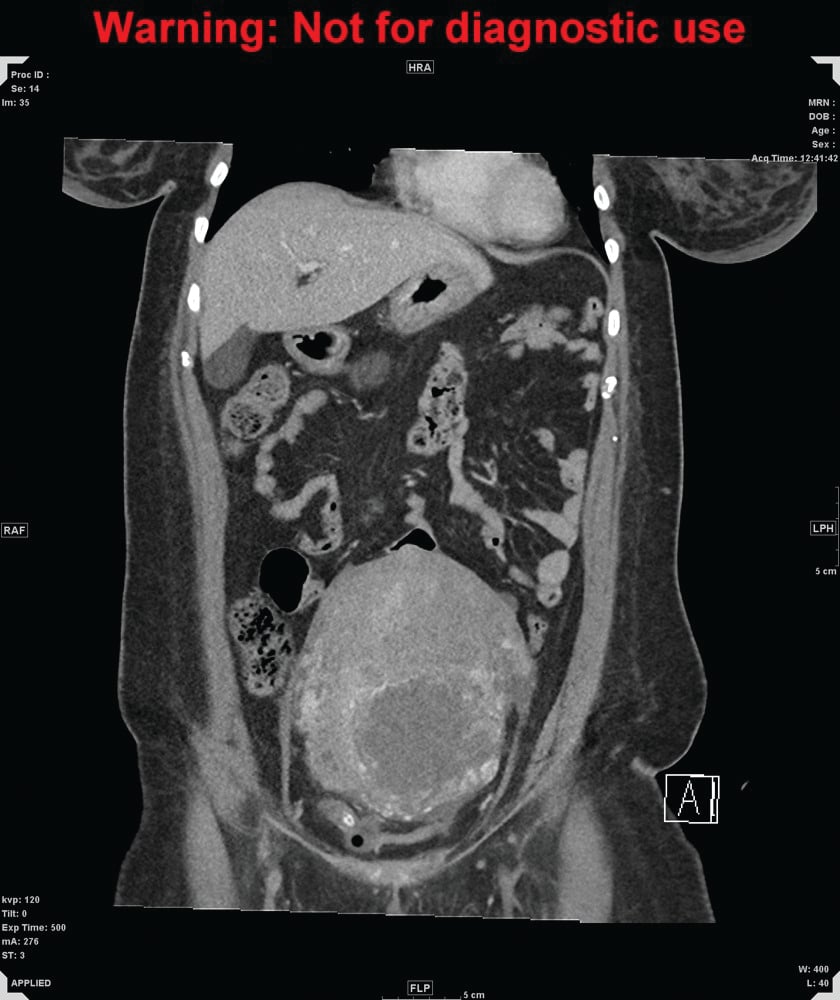

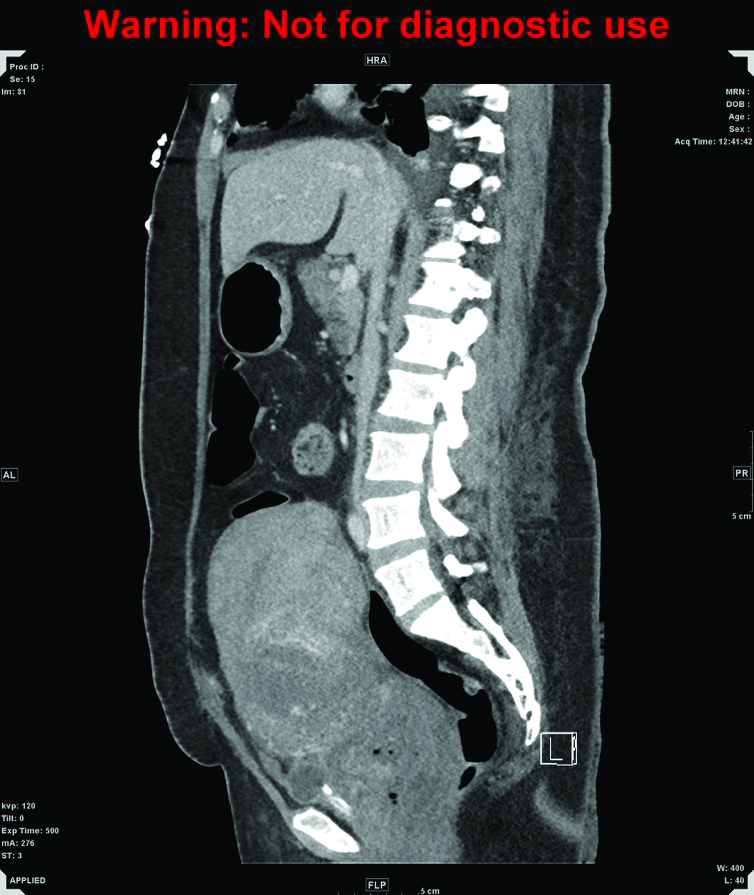

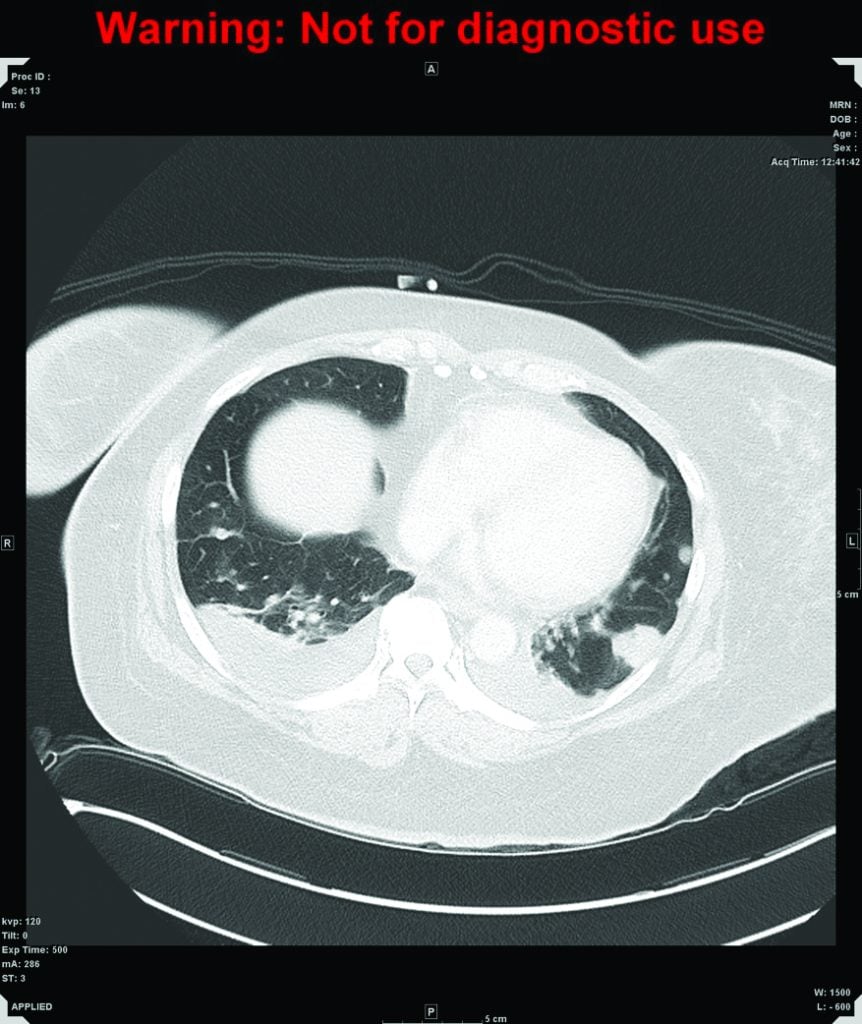

The initial b-hCG was 293,770 IU/L and increased to 459,459 IU/L nine days later. Both pelvic ultrasounds reported an empty gestational sac. Two weeks after the initial presentation, the patient experienced heavy bleeding. A repeat ultrasound reported a hypoechoic structure posterior to the endometrium, measuring 11mm by 16mm without vascularity; b-hCG was 512,000 IU/L. A dilation and curettage was performed the following day. A week after the procedure, she represented with vomiting, abdominal cramping, mild vaginal bleeding and biochemical thyrotoxicosis. The b-hCG had risen to 634,318 IU/L. The histology showed small foci of atypical avascular trophoblastic proliferation consistent with GTD. The differential diagnosis was recurrent or persistent GTD. The CT of chest, abdomen and pelvis (Figures 1 and 2) reported an enlarged uterus and multiple nodules in all lobes of both lungs consistent with lung metastases. She was diagnosed with stage three choriocarcinoma.

Figure 1a. CT of abdomen and pelvis, coronal

Figure 1b. CT of abdomen and pelvis, sagittal. A markedly enlarged uterus extends up to the level of the umbilicus, measuring 15 x 11 x 17cm in diameter, with heterogeneously enhancing walls and fluid in the endometrial canal.

Figure 2. CT of chest. Multiple nodules are scattered throughout the lung affecting both lungs and all lobes, consistent with lung metastases, with a halo of ground-glass change around the nodules which may be secondary to haemorrhage.

The patient was commenced on cisplatin and etoposide by medical oncology and was discharged with a plan for two further cycles of toposide and cisplatin as an outpatient, followed by EMA/CO (etoposide, methotrexate, actinomycin D, cyclophosphamide, vincristine) until two consecutive negative b-hCG readings.

She represented three days later with heavy vaginal bleeding. On examination, the uterus was palpable at the umbilicus. She was fluid resuscitated and received two packed red cell transfusions, syntocinon infusion, tranexamic acid and norethisterone tablets. She continued to bleed and was admitted to ICU for stabilisation. Interventional radiology (IR) attempted uterine artery embolisation (UAE). During the UAE, the patient began to cough and desaturate; the procedure was abandoned due to concerns that the presence of uterine arteriovenous malformation (AVM) led to lung emboli of the embozene particles. It is hypothesised that the AVM may be the cause of the choriocarcinoma pulmonary metastases.

One day post-IR procedure, the patient again had significant vaginal haemorrhage (more than 1200ml) and was taken to theatre for an emergency midline laparotomy and total hysterectomy (Figure 3), bilateral salpingectomy and right oophorectomy (the left ovary was not found). She was found to have a bleeding anterior vaginal wall metastasis. A vaginal pack was placed at the completion of the operation. On day one, her vaginal pack was removed as it was malodorous, which was followed by rapid vaginal blood loss of 2000ml and a haemoglobin drop to 69. The vagina was promptly repacked, with packing vigilantly changed every two days for the next two weeks. She received a total of 16 units of packed red cells, one pack of platelets and four packs of fresh frozen plasma during this admission. Her status improved with time. She received inpatient etoposide and cisplatin and was discharged. The patient has been well on EMA-CO chemotherapy. Her weekly b-hCG has been trending down well, with the most recent b-hCG being undetectable.

Figure 3. Uterus with myometrial invasion.

![Figure 4. The uterus with attached cervix weighed 1168g and measured 17cm in largest diameter. The choriocarcinoma tumour is composed of diffusely infiltrative sheets and nodules of trimorphic intermediate trophoblasts and cytotrophoblasts rimmed by multinucleated syncytiotrophoblasts with extensive haemorrhage and necrosis. Pleomorphism and mitotic activity is seen. The tumour involves more than 50 per cent of the myometrium and extends into the lower uterine segment and cervix. There is lymphovascular invasion. [H&E stain].](https://www.ogmagazine.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/choriocarcinoma-fig4-1024x821.jpg)

Figure 4. The uterus with attached cervix weighed 1168g and measured 17cm in largest diameter. The choriocarcinoma tumour is composed of diffusely infiltrative sheets and nodules of trimorphic intermediate trophoblasts and cytotrophoblasts rimmed by multinucleated syncytiotrophoblasts with extensive haemorrhage and necrosis. Pleomorphism and mitotic activity is seen. The tumour involves more than 50 per cent of the myometrium and extends into the lower uterine segment and cervix. There is lymphovascular invasion. [H&E stain].

Discussion

Choriocarcinoma is common, forming 90 per cent of GTN. It most often follows a molar pregnancy in 25–50 per cent of cases; but can also occur within 12 months of a non-molar pregnancy in 25 per cent of cases, or after a term pregnancy in 25–50 per cent of remaining cases.5

The incidence is difficult to report due to its low frequency and locational and ethnic variation, being more common among people of Asian backgrounds.6 The risk of malignant transformation of a molar pregnancy to GTN is 0.5–4 per cent after a partial mole and 15–25 per cent after a complete mole, as with our patient.7

Choriocarcinoma is the most aggressive type of GTN.8 They produce high levels of b-hCG2 and metastasise haematogenously to the lung, liver, kidneys, bowels and brain.9

Women with GTD may present with a large uterus for dates, pelvic pain, vaginal bleeding and hyperemesis gravidarum.10 Rarely, they will present with thyrotoxicosis, early onset severe preeclampsia and abdominal distension due to theca lutein cysts.11 12 There may be symptoms relating to the site of metastasis, including respiratory failure, neurological dysfunction, epigastric pain and jaundice from liver metastasis, nephrotic syndrome, and vaginal bleeding from vaginal metastases.13

Initial investigations include a quantitative b-hCG, thyroid function test, liver function test, coagulation profile, a group and screen, a urinary function test and a pelvic ultrasound. Chest imaging will assess for pulmonary metastasis. Histopathology from uterine curettage under ultrasound guidance is essential to obtain tissue diagnosis.

Follow up with serial b-hCG is a requirement for diagnosis of post-molar GTN.14 The RANZCOG criteria for diagnosis of GTN after a molar pregnancy is: a rise of more than nine per cent across three consecutive weekly values over a period of two weeks; a plateau or fall of less than ten per cent across four weekly measurements over a period of three weeks; or persistently elevated b-hCG levels at six months.15 GTN may also be diagnosed on histopathology.16 These patients need a metastatic work-up consisting of a gynaecology oncology tumour board review, blood investigations as previously listed, and imaging of the chest, abdomen and pelvis. Brain imaging is required if there are neurological deficits or pulmonary metastases, or upon diagnosis of choriocarcinoma.17

Treatment of GTN is usually by chemotherapy.18 The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) staging system (Table 1)19 and FIGO/WHO prognostic scoring system (Table 2)20 determine the best chemotherapy treatment regimen.21 A risk score of six or less is classified as low risk of resistance to single agent chemotherapy and is treated with methotrexate or actinomycin-D, while a score above six is considered high risk of resistance to monotherapy, requiring combination chemotherapy and possibly radiotherapy.22 The complete remission rate is 85 per cent and the five-year overall survival rate is 75–90 per cent.23

| Table 1. FIGO staging for GTN | |

FIGO Stage |

Description |

| I | Gestational trophoblastic tumours strictly confined to the uterine corpus |

| II | Gestational trophoblastic tumours extending to the adnexae or to the vagina, but limited to the genital structures |

| III | Gestational trophoblastic tumours extending to the lungs, with or without genital tract involvement |

| IV | All other metastatic sites. |

| Table 2. FIGO/WHO scoring system | ||||

| FIGO/WHO risk factor scoring with FIGO staging | 0 | 1 | 2 | 4 |

| Age | <40 | >40 | – | – |

| Antecedent pregnancy | mole | abortion | term | |

| Interval from index pregnancy (months) | <4 | 4–6 | 7–12 | >12 |

| Pretreatment hCG mIU/mL | <103 | >103–104 | >104–105 | >105 |

| Largest tumour size including uterus (cm) | – | 3–4 | ≥5 | – |

| Site of metatases including uterus | lung | spleen, kidney | gastrointestinal tract | brain, liver |

| Number of metatases identified | – | 1–4 | 5–8 | >8 |

| Previous failed chemotherapy | – | – | single drug | two or more drugs |

Fifty per cent of patients with high-risk metastatic GTN will require surgery to resect chemotherapy-resistant disease or to control complications such as bleeding.24 In circumstances where patients have completed their family, hysterectomy is recommended to reduce need for chemotherapy.25

Weekly hCG is required during chemotherapy until remission, defined as three consecutive weekly negative b-hCG.7 Following remission, two further consolidation therapy cycles are administered to prevent relapse.7 Post-treatment surveillance is carried out with monthly hCG until one year of normal hCG levels.7 It is prudent that the patient is on contraception during this time.

B-hCG should be sent six weeks following the completion of any future pregnancies regardless of the outcome of that pregnancy.26 Women should also undergo an early and mid-trimester ultrasound to confirm normal gestation, as there is a 5–10 per cent recurrence risk.27

It is important to record these patients on the GTD registry in Queensland, South Australia and Victoria.28 Registry on GTD should be established in all states.

Conclusion

Vigilant hCG monitoring is essential after molar pregnancy for early detection of post-molar GTN such as choriocarcinoma. Fortunately, choriocarcinoma is chemo-sensitive, allowing for good treatment response, as was seen in our patient’s rapidly dropping hCG levels.

References

- RANZCOG Statement for the management of gestational trophoblastic disease. RANZCOG 2013. 17p. Available from: www.ranzcog.edu.au/RANZCOG_SITE/media/RANZCOG-MEDIA/Women%27s%20Health/Statement%20and%20guidelines/Clinical%20-%20Gynaecology/Management-of-Gestational-Trophoblastic-Disease-(C-Gyn-31)-New-Statement-Nov13.pdf?ext=.pdf.

- Baergen RN. Gestational trophoblastic disease: Pathology. UpToDate Mar 2017. Available from: www.uptodate.com/contents/gestational-trophoblastic-disease-pathology.

- RANZCOG Statement for the management of gestational trophoblastic disease. RANZCOG 2013. 17p. Available from: www.ranzcog.edu.au/RANZCOG_SITE/media/RANZCOG-MEDIA/Women%27s%20Health/Statement%20and%20guidelines/Clinical%20-%20Gynaecology/Management-of-Gestational-Trophoblastic-Disease-(C-Gyn-31)-New-Statement-Nov13.pdf?ext=.pdf.

- RANZCOG Statement for the management of gestational trophoblastic disease. RANZCOG 2013. 17p. Available from: www.ranzcog.edu.au/RANZCOG_SITE/media/RANZCOG-MEDIA/Women%27s%20Health/Statement%20and%20guidelines/Clinical%20-%20Gynaecology/Management-of-Gestational-Trophoblastic-Disease-(C-Gyn-31)-New-Statement-Nov13.pdf?ext=.pdf.

- RANZCOG Statement for the management of gestational trophoblastic disease. RANZCOG 2013. 17p. Available from: www.ranzcog.edu.au/RANZCOG_SITE/media/RANZCOG-MEDIA/Women%27s%20Health/Statement%20and%20guidelines/Clinical%20-%20Gynaecology/Management-of-Gestational-Trophoblastic-Disease-(C-Gyn-31)-New-Statement-Nov13.pdf?ext=.pdf.

- RANZCOG Statement for the management of gestational trophoblastic disease. RANZCOG 2013. 17p. Available from: www.ranzcog.edu.au/RANZCOG_SITE/media/RANZCOG-MEDIA/Women%27s%20Health/Statement%20and%20guidelines/Clinical%20-%20Gynaecology/Management-of-Gestational-Trophoblastic-Disease-(C-Gyn-31)-New-Statement-Nov13.pdf?ext=.pdf.

- RANZCOG Statement for the management of gestational trophoblastic disease. RANZCOG 2013. 17p. Available from: www.ranzcog.edu.au/RANZCOG_SITE/media/RANZCOG-MEDIA/Women%27s%20Health/Statement%20and%20guidelines/Clinical%20-%20Gynaecology/Management-of-Gestational-Trophoblastic-Disease-(C-Gyn-31)-New-Statement-Nov13.pdf?ext=.pdf.

- Baergen RN. Gestational trophoblastic disease: Pathology. UpToDate Mar 2017. Available from: www.uptodate.com/contents/gestational-trophoblastic-disease-pathology.

- Ngan HYS, Seckl MJ, et al. FIGO cancer reports 2015: Update on the diagnosis and management of gestational trophoblastic disease. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2015 Sep;131:123-126.

- Ngan HYS, Seckl MJ, et al. FIGO cancer reports 2015: Update on the diagnosis and management of gestational trophoblastic disease. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2015 Sep;131:123-126.

- Baergen RN. Gestational trophoblastic disease: Pathology. UpToDate Mar 2017. Available from: www.uptodate.com/contents/gestational-trophoblastic-disease-pathology.

- Ngan HYS, Seckl MJ, et al. FIGO cancer reports 2015: Update on the diagnosis and management of gestational trophoblastic disease. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2015 Sep;131:123-126.

- Berkowitz RS, Goldstein DP, et al. Hydatidiform mole: Epidemiology, clinical features & diagnosis. UpToDate Apr 2017. Available from: www.uptodate.com/contents/hydatidiform-mole-epidemiology-clinical-features-and-diagnosis.

- Ngan HYS, Seckl MJ, et al. FIGO cancer reports 2015: Update on the diagnosis and management of gestational trophoblastic disease. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2015 Sep;131:123-126.

- RANZCOG Statement for the management of gestational trophoblastic disease. RANZCOG 2013. 17p. Available from: www.ranzcog.edu.au/RANZCOG_SITE/media/RANZCOG-MEDIA/Women%27s%20Health/Statement%20and%20guidelines/Clinical%20-%20Gynaecology/Management-of-Gestational-Trophoblastic-Disease-(C-Gyn-31)-New-Statement-Nov13.pdf?ext=.pdf.

- RANZCOG Statement for the management of gestational trophoblastic disease. RANZCOG 2013. 17p. Available from: www.ranzcog.edu.au/RANZCOG_SITE/media/RANZCOG-MEDIA/Women%27s%20Health/Statement%20and%20guidelines/Clinical%20-%20Gynaecology/Management-of-Gestational-Trophoblastic-Disease-(C-Gyn-31)-New-Statement-Nov13.pdf?ext=.pdf.

- Berkowitz RS, Goldstein DP, et al. Hydatidiform mole: Epidemiology, clinical features & diagnosis. UpToDate Apr 2017. Available from: www.uptodate.com/contents/hydatidiform-mole-epidemiology-clinical-features-and-diagnosis.

- Ngan HYS, Seckl MJ, et al. FIGO cancer reports 2015: Update on the diagnosis and management of gestational trophoblastic disease. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2015 Sep;131:123-126.

- Ngan, HYS, Seckl MJ, et al. FIGO cancer reports 2015: Update on the diagnosis and management of gestational trophoblastic disease. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2015;131:123-126. Figure 5, FIGO staging for GTN; Figure 6, FIGO/WHO scoring system [cited 2017 Nov 18]. Available from: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1016/j.ijgo.2015.06.008/full.

- Ngan, HYS, Seckl MJ, et al. FIGO cancer reports 2015: Update on the diagnosis and management of gestational trophoblastic disease. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2015;131:123-126. Figure 5, FIGO staging for GTN; Figure 6, FIGO/WHO scoring system [cited 2017 Nov 18]. Available from: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1016/j.ijgo.2015.06.008/full.

- Sydney Gynaecological Oncology Group. Gestational Trophoblastic Disease. Sydney Cancer Centre: 2017. Available from: www.slhd.nsw.gov.au/services/sgog/GTD_Guide.html.

- Sydney Gynaecological Oncology Group. Gestational Trophoblastic Disease. Sydney Cancer Centre: 2017. Available from: www.slhd.nsw.gov.au/services/sgog/GTD_Guide.html.

- Ngan HYS, Seckl MJ, et al. FIGO cancer reports 2015: Update on the diagnosis and management of gestational trophoblastic disease. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2015 Sep;131:123-126.

- Ngan HYS, Seckl MJ, et al. FIGO cancer reports 2015: Update on the diagnosis and management of gestational trophoblastic disease. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2015 Sep;131:123-126.

- Sydney Gynaecological Oncology Group. Gestational Trophoblastic Disease. Sydney Cancer Centre: 2017. Available from: www.slhd.nsw.gov.au/services/sgog/GTD_Guide.html.

- RANZCOG Statement for the management of gestational trophoblastic disease. RANZCOG 2013. 17p. Available from: www.ranzcog.edu.au/RANZCOG_SITE/media/RANZCOG-MEDIA/Women%27s%20Health/Statement%20and%20guidelines/Clinical%20-%20Gynaecology/Management-of-Gestational-Trophoblastic-Disease-(C-Gyn-31)-New-Statement-Nov13.pdf?ext=.pdf.

- RANZCOG Statement for the management of gestational trophoblastic disease. RANZCOG 2013. 17p. Available from: www.ranzcog.edu.au/RANZCOG_SITE/media/RANZCOG-MEDIA/Women%27s%20Health/Statement%20and%20guidelines/Clinical%20-%20Gynaecology/Management-of-Gestational-Trophoblastic-Disease-(C-Gyn-31)-New-Statement-Nov13.pdf?ext=.pdf.

- RANZCOG Statement for the management of gestational trophoblastic disease. RANZCOG 2013. 17p. Available from: www.ranzcog.edu.au/RANZCOG_SITE/media/RANZCOG-MEDIA/Women%27s%20Health/Statement%20and%20guidelines/Clinical%20-%20Gynaecology/Management-of-Gestational-Trophoblastic-Disease-(C-Gyn-31)-New-Statement-Nov13.pdf?ext=.pdf.

Leave a Reply