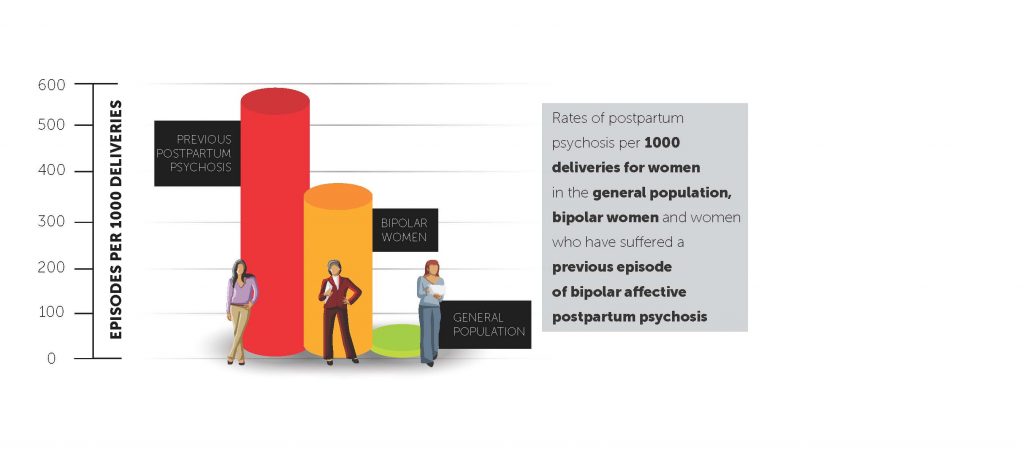

Postpartum or ‘puerperal’ psychosis, the acute onset of severe psychiatric symptoms early postpartum, was first characterised in the 19th century. At that time, many cases were likely organic as a result of blood loss or sepsis. However, in some cases, there were no underlying medical risk factors and the concept of non-organic postpartum psychosis was developed. In the 21st century, the rate of postpartum psychotic episodes is 1–2/1000 deliveries in the parturient population, increasing dramatically to 30 per cent of women with a history of bipolar disorder and more than 50 per cent in women with a past postpartum psychosis (Figure 1).1 A woman has a 30-fold increased risk for acute psychosis in the first three weeks postpartum.2

Figure 1. Rates of postpartum psychosis in women

Clinical features

Very early signs of postpartum psychosis include increasingly anxious affect and poor sleep (independent of baby waking). As these symptoms are common in parturient women, it is important to review at regular intervals for symptom evolution. As psychosis evolves, women develop irrational and frightening beliefs (for example, harm will befall them, their family or infant; close family can no longer be trusted; they are ‘going mad’; or the baby will be removed because they are a ‘bad’ mother). Women are very likely to minimise symptoms and go undiagnosed early on. At mental state examination, they present as preoccupied, suspicious, difficult to engage, restless, distractable or disorganised. Depending on symptom severity, their speech may be illogical and difficult to follow, and they may experience frank delusions (for example, grandiose, persecutory, guilt). More often, these women may express vague suspicions that close family members can’t be trusted or concerns about their baby’s welfare. They may experience suicidal thoughts, especially if distressed by persecutory or depressive delusions. These women may have partial or no insight into their disturbed mental state. Psychotic symptoms and insight often fluctuate day to day, and, as the episode worsens, symptoms are associated with significantly impaired ability to care for the baby. Both suicidality and possible thoughts of harm to baby, as part of a psychotic belief system or severe depression, need to be specifically explored.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of acute psychosis is very straightforward when symptoms are severe. However, in milder cases where there is commonly symptom minimisation, partial insight and day-to-day fluctuation, these women may present well at cross-sectional assessment. It is thus critical to obtain corroborative history from significant others and, if possible, to review the woman at regular, close intervals. If unsure, urgent psychiatric consultation is essential.

An obstetrician’s immediate management plan:

- Engage both the woman and her significant other/s and try to destigmatise the mental health issues as much as possible while highlighting the need for urgent care.

- Ensure the safety of infant and mother.

- Discuss the diagnosis in broad terms: avoid the term psychosis; use terms like ‘more severe postnatal depression’.

- Emphasise that sleep deprivation is a key risk factor and highlight the need to urgently commence a hypnotic.

- Consider a hypnotic with a long half-life. For example, half to one tablet of zopiclone (Imovane) or doxylamine (Restavit). Temazepam is unlikely to be useful. Hypnotics are relatively safe in breastfeeding, as there is minimal secretion into breastmilk.

- Discuss possible admission to a mother and baby unit (MBU). Emphasise the value of the MBU for support with the baby. Again, try to reduce the mother’s/family’s stigma with a psychiatric admission.

- As soon as possible, seek advice from and hand over care to psychiatry and the local mental health team.

Short and longer-term management

Medication

Once the woman is engaged with psychiatry, a sedating antipsychotic, such as quetiapine (Seroquel), will need to be commenced. Initially, this is to reduce symptoms of agitation, distress and insomnia while the antipsychotic takes effect within one to three weeks. Response to the antipsychotic needs close monitoring and, all going well, reduction and cessation after six months (if this is the woman’s first episode of psychosis) can be undertaken.

Where a woman has a pre-existing diagnosis of bipolar disorder or schizophrenia or develops such a diagnosis, appropriate longer-term antipsychotic and/or mood stabilisers will need to be re/commenced. If lithium is to be commenced while breastfeeding, it is best to seek a second opinion, where possible from a perinatal psychiatrist.

Psychoeducation

It is important to explain the difference between postnatal depression and postpartum psychosis. Reassure the woman and her family about the overall good prognosis of postpartum psychosis, while emphasising the need for psychiatric monitoring and medication in subsequent months. Women and their families need to learn about the early signs of relapse of psychosis, most commonly: insomnia, independent of baby’s waking; racing thoughts; erratic mood shift or severe anxiety; distractibility; or unfounded preoccupation with the baby or family’s welfare.

Future pregnancy planning

Subsequent pregnancy is not contraindicated, but best deferred until the woman has been free of symptoms for over a year. Families also need to be aware that having had one postpartum psychosis increases a woman’s chance of a recurrence to about 50 per cent, but early management of postnatal insomnia with medication and close mental health monitoring is likely to reduce the chance of relapse substantially. It is important to devise a clear mental healthcare plan with the woman and her family for any subsequent pregnancy. Copies of this plan need to be made available to the woman and all key healthcare providers.

Prognosis

Postpartum psychosis usually responds fairly quickly (within two to three weeks) to antipsychotic medication and sleep restoration. However, some cases take much longer to resolve and it is possible these women are developing a longer-term psychiatric condition, either a bipolar disorder or, less commonly, a schizophrenia-like illness. While the majority of women with a de novo episode don’t relapse into psychosis later in life, 14 per cent will go on to develop a manic or depressive episode sometime in the next 15 or more years,3 consistent with an emerging bipolar disorder.

Case vignette one

A 35-year-old married woman with bipolar disorder, requiring several admissions in her teens, responded fully to lithium at the time, but ceased all medication and psychiatric follow-up in her 20s. She remained well on a regimen of regular sleep, supportive work situation and partner relationship, cessation of alcohol or drug use; and minimising of life stressors. Occasional bursts of mood lability lasting a few days would resolve with improved sleep. At enquiry in pregnancy, she reported having been ‘a bit depressed’ after a relationship breakup in her teens, but did not mention the bipolar disorder.

Pregnancy was uneventful until she was admitted to hospital at 26 weeks for management of severe hypertension. In hospital, sleep was broken. She missed the support of her husband and the structure of work. She became increasingly anxious about the delivery as her blood pressure worsened and had to stay in hospital to term. Following caesarean section, she became severely sleep deprived and suspicious of staff, labile in mood, wanting to go home against medical advice, and declining a hypnotic. By day three, she was chaotic and pressured in speech, irritable, voicing persecutory delusions (staff wanting to poison her with medication), unable to be contained on the postnatal ward and was transferred to a locked psychiatric unit. After several trials of antipsychotic and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), she finally accepted lithium which rapidly led to full symptomatic recovery, though it took another year before she was functioning optimally and able to return to work. A great deal of planning took place for her second pregnancy, which was managed with low-dose seroquel in late pregnancy and postpartum to guarantee good sleep while her husband did expressed feeds at night. She did not relapse or need to recommence lithium and, two years later, remained well unmedicated, but vigilant around sleep hygiene and managing stress.

Case vignette two

A 40-year-old married woman was ambivalent about having a child. There was no past psychiatric history, but her sister had suffered severe postnatal depression. An unremarkable pregnancy was followed by a traumatic emergency caesarean section for fetal distress. She reported a sense of not being connected to the baby and not wanting to breastfeed or care for her baby. She was finding sleep deprivation very challenging, but declined a hypnotic. On the morning of postpartum day four, she expressed vague concerns about the presence of CCTV cameras in the hospital, was wanting baby to stay with staff, and worried that some staff had taken a dislike to her. That afternoon, however, she was settled and not voicing any concerns. On the afternoon of day five, she shoved the baby aside when it was brought in to feed and narrowly missed dropping the baby. She was scheduled to the psychiatric unit and discharged home three weeks later, much improved on a moderate dose of quetiapine.

Case vignette three

A 40-year-old married woman was having her first baby and did not report a psychiatric history. She had an induction and forceps delivery, with moderate postpartum haemorrhage of 700ml and Hb 9.5 (no prior level was available). At review 36 hours later, staff reported she had been ‘inappropriate’ during the second stage of labour and had not slept for two nights because of high anxiety levels. No hypnotic had been offered. She was concerned that her baby might not be safe on the ward unless she watched over it day and night. At times, she was noted to be walking up and down the corridor vaguely ‘looking for my baby’. At mental state examination, her affect was a little odd and fearful. It was difficult to follow her train of thought. She expressed fears for her baby’s welfare and a belief that he had been kidnapped by the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (ASIO). She was intermittently confused about the date and time of delivery and whether she should breastfeed as ‘baby told me it was not hungry’. She lacked insight into her disturbed mental state.

A working diagnosis of acute confusional state was made, pending investigations, with differential diagnosis of postpartum psychosis. Hb that day returned as 5.3. After transfusion and regular hypnotic, her mental state settled back to normal over the next three days, confirming the diagnosis of acute confusional state.

Conclusions

The first two cases illustrate the need to carefully seek past or family psychiatric history (though this may be denied or understated). All cases demonstrate a lack of response by staff to severe sleep deprivation, with lack of use of hypnotic medication and the need to review symptoms at very regular intervals. Symptoms often rapidly evolve. The fluctuating nature and subtlety of symptoms was associated with difficulty with early detection in case two. Case three had some features suggestive of an acute confusional state, with fleeting auditory hallucinations, disorientation to time and worsening symptoms at night. However, it also met criteria for postpartum psychosis. Case three emphasises the need to routinely exclude organic pathology, however unlikely that might be.

Acute postpartum mental disturbance can range from mild symptoms, resolving with sleep restoration, through to more severe and florid presentations requiring antipsychotic treatment, and often hospitalisation. Severe cases are considered a psychiatric emergency, while possible incipient cases need to be assessed at close repeated intervals, ideally after sleep restoration and with as much corroborative history as possible.

Obstetricians and midwives must be mindful of the possibility of postpartum psychosis and the risk of rapid escalation, with the need for early involvement of a psychiatrist. In patients with a prior history, a multidisciplinary team approach, a management plan, attention to avoidance of sleep deprivation in the third trimester, early intervention with hypnotic or antipsychotic medication, and a low threshold for transfer to a psychiatric facility or mother and baby unit, should be considered.

Acknowledgement

I gratefully acknowledge feedback from Dr Vijay Roach, President-elect of the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists.

References

- Jones I, Chandra P, Dazzan P, et al. Bipolar disorder, affective psychosis, and schizophrenia in pregnancy and the postpartum period. Lancet 2014 Nov 15;384(9956):1789-1799.

- Munk-Olsen T, Laursen T, Pedersen C, et al. New parents and mental disorders: a population-cased register study. JAMA 2006 Dec 06;296(21):2582-2589.

- Munk-Olsen T, Laursen T, Meltzer-Brody S, et al. Psychiatric disorders with postpartum onset: possible early manifestations of bipolar affective disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2012 April; 69(4):428-434.

Leave a Reply