Anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDA-R) encephalitis is a paraneoplastic limbic syndrome caused by ovarian teratomas. Neural tissue in a teratoma can trigger the production of anti-NMDA-R antibodies,1 which causes neuronal dysfunction and loss by altering the neuronal cell-surface NMDA receptors in the limbic system.2 This syndrome presents with a range of psychiatric, neurological and autonomic features3 and is associated with long-term morbidity and mortality. We will review the three cases that presented to our institution over a period of 12 months.

Case one

A 23-year-old woman presented with a two-week history of lethargy, emotional lability, involuntary movements, increasing forgetfulness and falls. On examination, the patient was alert but acutely confused. Examination and initial investigations were normal. The patient was admitted for empiric intravenous antibiotics for meningitis, as the lumbar puncture revealed a high white cell count, but her clinical condition deteriorated. An EEG and brain MRI was normal. A CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis revealed a 12cm multi-loculated pelvic mass, likely an ovarian teratoma (Figure 1).

Figure 1. CT abdomen/pelvis (Coronal and Sagittal): A 12x7x11cm multi-loculated solid and cystic pelvic mass, with punctate calcified and fat density foci in keeping with a large ovarian teratoma. No ascites, peritoneal or pulmonary disease, lymphadenopathy or bony lesions. Courtesy of Liverpool Hospital Radiology Department.

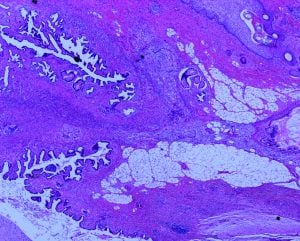

After anti-NMDA-R antibodies were detected in serum and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), the gynaecological oncology team performed a right salpingo-oophrectomy on day eight of admission. Histopathology was consistent with mature cystic teratoma (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Histology slide. Right ovary specimen weight 427g. The ovarian mass contains a multi-loculated cyst with solid and cystic areas. Findings are consistent with a mature teratoma containing focal calcification, with hair-like material, skin with adnexal structures, bone, cartilage, serous fluid, abundant mature neural tissue and tissue resembling choroid plexus. [H&E stain]. Image courtesy of Liverpool Hospital Anatomical Pathology.

Case two

A 25-year-old woman presented with headache, lethargy, acute confusion and a subjective fever. She was known to have hypertension and type 2 diabetes.

On review, she was acutely disoriented and her BP was 184/126. The initial examination, investigations and imaging were normal. She had a high white cell count on lumbar puncture and treatment was started for suspected meningitis/encephalitis with benzylpenicillin, ceftriaxone and acyclovir. Soon after, methylprednisolone was added for autoimmune encephalitis and the antibiotics were changed to tazocin for suspected sepsis, as she developed low grade temperatures. Her blood pressure remained refractory to multiple drugs.

The patient continued to have behavioural disturbances with aggression, violent outbursts, disinhibition and hyperactivity, requiring olanzapine and quetiapine. Despite a normal EEG, the patient had tonic-clonic and focal seizures, requiring sodium valproate, levetiracetam and midazolam. Anti-NMDA-R antibodies were found in the CSF and serum. It became apparent that she had autonomic dysfunction, causing severe hypertension, tachycardia and pyrexia.

Due to a fluctuating Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS), she was intubated and sedated, but continued to demonstrate focal rhythmic eye and upper limb movements. A pelvic ultrasound and CT scan reported a small right ovarian teratoma for which she had a laparoscopic right salpingo-oophrectomy on day 11 of admission, confirming mature cystic teratoma. Unfortunately, her clinical condition didn’t improve and she continued to have involuntary facial and limb movements, catatonia and status epilepticus. She proceeded to have IVIG, steroid therapy, rituximab, plasmapheresis and plasma exchange. The presence of a left teratoma could not be confirmed on imaging and after extensive multidisciplinary consultation, the decision was made to remove the left ovary as well. The final pathology was negative for a teratoma.

Twelve months after her first surgery, this patient still has persisting neurological and autonomic dysfunction and remains hospitalised. She was intubated for eight months and is receiving immunotherapy to date.

Case three

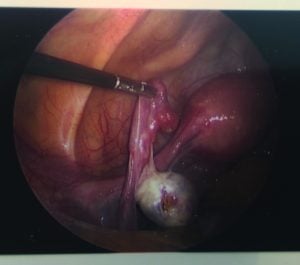

A 37-year-old presented with syncope, seizure activity, confusion and behavioural changes. She was initially discharged with a presumed new diagnosis of epilepsy. She was admitted after her third presentation, eight days after the initial presentation. On this admission, she was diagnosed with anti-NMDA-R encephalitis on serum and CSF serology, secondary to an 18mm left ovarian dermoid seen on imaging. She underwent a laparoscopic left salpingo-oophrectomy on day 15 of her admission (Figure 3). Histology confirmed mature cystic teratoma. Postoperatively, she received IVIG, plasmapheresis and rituximab and was extubated on day 25.

Figure 3. Left ovarian dermoid seen on laparoscopy.

Discussion

Anti-NMDA-R encephalitis was initially described in 1997 in two young women who presented with psychiatric symptoms, an ovarian teratoma and altered levels of consciousness, with improvement upon removal of the tumour.4 The mean age is 245 and the syndrome starts with a viral-like illness, including headache, nausea, vomiting, fever and lethargy and then progresses to a spectrum of neuropsychiatric symptoms.6

Early stage symptoms include confusion, personality changes, memory deficits, psychosis, mood disturbances, self-harming behaviours, seizures and facial and limb movement disorders.7 8 9 This can progress to decreased GCS requiring ventilator support,10 11 hypoventilation, autonomic instability including hypotension or hypertension, bradycardia or tachycardia and hyperthermia.12 As anti-NMDA-R encephalitis is uncommon, diagnosis is often delayed, while more common conditions such as neuro-psychotic conditions and infective encephalitis are being considered.13

In patients with acute neurologic findings, initial investigations for encephalitis should be initiated, including serum and CSF studies.14 Definitive diagnosis is made by the confirmation of anti-NMDA-R antibodies in the blood or CSF.15 This is followed by imaging to confirm ovarian teratoma. Timely diagnosis and surgery are essential to reduce risk of permanent neurological injury,16 17 as delayed surgery can result in autonomic instability, catatonia, status epilepticus, coma and death.18 There is substantial neurological improvement in 80 per cent of patients who undergo tumour excision and immunotherapy.19

In two of our cases, the symptoms improved within a month of surgery and immunosuppressive treatment, although recovery can continue for up to 24 months.4 First-line treatment includes immunotherapy with IV steroids, IVIG or plasmapheresis and second line treatment is rituximab and cyclophosphamide.20 21 Anticonvulsive therapy is often employed.22

Occasionally, the syndrome may be caused by microscopic tumours undetectable by imaging.23 In these scenarios, treatment should be medical with immunotherapy. Surgery is not recommended, as it may result in removal of histologically normal ovaries.note]Acien P, Acien M, Ruiz-Macia E, et al. Ovarian teratoma-associated anti-NMDAR encephalitis: a systematic review of reported cases. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2017; June 19;9(157). Available from:www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4203903/DOI: 10.1186/s13023-014-0157-x.[/note] There have been a few cases of ovarian teratomas being detected years after a diagnosis of anti-NMDA-R encephalitis. Patients without detectable tumours should continue immunotherapy for a minimum of 12 months and be screened with imaging every six months for four years for the presence of an ovarian teratoma.24 There have also been reports of recurrent teratomas with recurrent encephalitis,25 26 while others have presented with encephalitis months to years following removal of the teratoma. The mean time to recovery is around 3.6 months, but permanent sequelae is seen in 10 per cent of patients, and seven per cent die from encephalitis-related complications.27

Contraceptive use is essential while on long-term immunotherapy, especially long-acting reversible contraceptives, as patients often have residual cognitive and memory impairment that makes compliance difficult.28

Conclusion

The gynaecologist has an important role to play within the multidisciplinary team caring for these patients.29 A high index of suspicion for this serious and potentially fatal condition,30 and early tumour detection and removal result in improved prognosis.31 While the majority of ovarian teratomas won’t trigger the development of anti-NMDA-R encephalitis, the patient and their family should be alerted to report any new onset neuropsychiatric or behavioural changes if a teratoma is diagnosed and expectant management is pursued.32

References

- Acien P, Acien M, Ruiz-Macia E, et al. Ovarian teratoma-associated anti-NMDAR encephalitis: a systematic review of reported cases. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2017; June 19;9(157). Available from:www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4203903/DOI: 10.1186/s13023-014-0157-x.

- Barbieri R, Clark R. Ovarian teratoma (dermoid cyst) and encephalitis: a link to keep on your radar. OBG Manag. 2014;26(1):12,15,16. Available from:www.mdedge.com/…/article/…/ovarian-teratoma-dermoid-cyst-and-encephalitis-link.

- Tibulaer M, McCracken L, Gabilondo I, et al. Treatment and prognostic factors for long-term outcome in patients with anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis: an observational cohort study. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12(2):157-65. Available from:www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23290630.

- Braverman J, Marcus C, Garg R. Anti-NMDA-receptor encephalitis: a neuropsychiatric syndrome associated with ovarian teratoma. Gynacol Oncol Rep. 2015;14: 1-3. Available from:www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4688824/

- Acien P, Acien M, Ruiz-Macia E, et al. Ovarian teratoma-associated anti-NMDAR encephalitis: a systematic review of reported cases. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2017; June 19;9(157). Available from:www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4203903/DOI: 10.1186/s13023-014-0157-x.

- Acien P, Acien M, Ruiz-Macia E, et al. Ovarian teratoma-associated anti-NMDAR encephalitis: a systematic review of reported cases. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2017; June 19;9(157). Available from:www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4203903/DOI: 10.1186/s13023-014-0157-x.

- Acien P, Acien M, Ruiz-Macia E, et al. Ovarian teratoma-associated anti-NMDAR encephalitis: a systematic review of reported cases. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2017; June 19;9(157). Available from:www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4203903/DOI: 10.1186/s13023-014-0157-x.

- Braverman J, Marcus C, Garg R. Anti-NMDA-receptor encephalitis: a neuropsychiatric syndrome associated with ovarian teratoma. Gynacol Oncol Rep. 2015;14: 1-3. Available from:www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4688824/.

- Dalmau J, Lancaster E, Martinez-Hernandez E, et al. Clinical experience and laboratory investigations in patients with anti-NMDAR encephalitis. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10(1):63-74. Available from:www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21163445

- Acien P, Acien M, Ruiz-Macia E, et al. Ovarian teratoma-associated anti-NMDAR encephalitis: a systematic review of reported cases. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2017; June 19;9(157). Available from:www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4203903/DOI: 10.1186/s13023-014-0157-x.

- Dalmau J, Lancaster E, Martinez-Hernandez E, et al. Clinical experience and laboratory investigations in patients with anti-NMDAR encephalitis. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10(1):63-74. Available from:www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21163445.

- Braverman J, Marcus C, Garg R. Anti-NMDA-receptor encephalitis: a neuropsychiatric syndrome associated with ovarian teratoma. Gynacol Oncol Rep. 2015;14: 1-3. Available from:www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4688824/.

- Braverman J, Marcus C, Garg R. Anti-NMDA-receptor encephalitis: a neuropsychiatric syndrome associated with ovarian teratoma. Gynacol Oncol Rep. 2015;14: 1-3. Available from:www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4688824/.

- Braverman J, Marcus C, Garg R. Anti-NMDA-receptor encephalitis: a neuropsychiatric syndrome associated with ovarian teratoma. Gynacol Oncol Rep. 2015;14: 1-3. Available from:www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4688824/.

- Braverman J, Marcus C, Garg R. Anti-NMDA-receptor encephalitis: a neuropsychiatric syndrome associated with ovarian teratoma. Gynacol Oncol Rep. 2015;14: 1-3. Available from:www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4688824/.

- Barbieri R, Clark R. Ovarian teratoma (dermoid cyst) and encephalitis: a link to keep on your radar. OBG Manag. 2014;26(1):12,15,16. Available from:www.mdedge.com/…/article/…/ovarian-teratoma-dermoid-cyst-and-encephalitis-link.

- Braverman J, Marcus C, Garg R. Anti-NMDA-receptor encephalitis: a neuropsychiatric syndrome associated with ovarian teratoma. Gynacol Oncol Rep. 2015;14: 1-3. Available from:www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4688824/.

- Braverman J, Marcus C, Garg R. Anti-NMDA-receptor encephalitis: a neuropsychiatric syndrome associated with ovarian teratoma. Gynacol Oncol Rep. 2015;14: 1-3. Available from:www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4688824/.

- Braverman J, Marcus C, Garg R. Anti-NMDA-receptor encephalitis: a neuropsychiatric syndrome associated with ovarian teratoma. Gynacol Oncol Rep. 2015;14: 1-3. Available from:www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4688824/.

- Tibulaer M, McCracken L, Gabilondo I, et al. Treatment and prognostic factors for long-term outcome in patients with anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis: an observational cohort study. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12(2):157-65. Available from:www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23290630.

- Dalmau J, Lancaster E, Martinez-Hernandez E, et al. Clinical experience and laboratory investigations in patients with anti-NMDAR encephalitis. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10(1):63-74. Available from:www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21163445.

- Acien P, Acien M, Ruiz-Macia E, et al. Ovarian teratoma-associated anti-NMDAR encephalitis: a systematic review of reported cases. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2017; June 19;9(157). Available from:www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4203903/DOI: 10.1186/s13023-014-0157-x

- Braverman J, Marcus C, Garg R. Anti-NMDA-receptor encephalitis: a neuropsychiatric syndrome associated with ovarian teratoma. Gynacol Oncol Rep. 2015;14: 1-3. Available from:www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4688824/.

- Braverman J, Marcus C, Garg R. Anti-NMDA-receptor encephalitis: a neuropsychiatric syndrome associated with ovarian teratoma. Gynacol Oncol Rep. 2015;14: 1-3. Available from:www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4688824/.

- Acien P, Acien M, Ruiz-Macia E, et al. Ovarian teratoma-associated anti-NMDAR encephalitis: a systematic review of reported cases. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2017; June 19;9(157). Available from:www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4203903/DOI: 10.1186/s13023-014-0157-x.

- Tibulaer M, McCracken L, Gabilondo I, et al. Treatment and prognostic factors for long-term outcome in patients with anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis: an observational cohort study. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12(2):157-65. Available from:www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23290630.

- Acien P, Acien M, Ruiz-Macia E, et al. Ovarian teratoma-associated anti-NMDAR encephalitis: a systematic review of reported cases. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2017; June 19;9(157). Available from:www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4203903/DOI: 10.1186/s13023-014-0157-x

- Braverman J, Marcus C, Garg R. Anti-NMDA-receptor encephalitis: a neuropsychiatric syndrome associated with ovarian teratoma. Gynacol Oncol Rep. 2015;14: 1-3. Available from:www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4688824/.

- Braverman J, Marcus C, Garg R. Anti-NMDA-receptor encephalitis: a neuropsychiatric syndrome associated with ovarian teratoma. Gynacol Oncol Rep. 2015;14: 1-3. Available from:www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4688824/.

- Acien P, Acien M, Ruiz-Macia E, et al. Ovarian teratoma-associated anti-NMDAR encephalitis: a systematic review of reported cases. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2017; June 19;9(157). Available from:www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4203903/DOI: 10.1186/s13023-014-0157-x.

- Braverman J, Marcus C, Garg R. Anti-NMDA-receptor encephalitis: a neuropsychiatric syndrome associated with ovarian teratoma. Gynacol Oncol Rep. 2015;14: 1-3. Available from:www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4688824/.

- Barbieri R, Clark R. Ovarian teratoma (dermoid cyst) and encephalitis: a link to keep on your radar. OBG Manag. 2014;26(1):12,15,16. Available from:www.mdedge.com/…/article/…/ovarian-teratoma-dermoid-cyst-and-encephalitis-link.

Something never heard of -teratoma and encephalitis

Thanks for information