A 47-year-old pre-menopausal woman presented describing severe pain in the left iliac fossa and abdomen. This was associated with nausea and vomiting but normal bowel movements. The patient was multiparous (normal vaginal deliveries) and was using the combined oral contraceptive pill to manage irregular and heavy menstrual bleeding of a known multifibroid uterus. Cervical screening was normal and up to date. Relevant history featured multiple sclerosis managed by natalizumab. The patient had never undergone any abdomino-pelvic surgery.

Clinical examination revealed normal vital signs but a tender abdomen (most prominent in the left iliac fossa). There were no features of peritonism. Bowel sounds were present, noted to high-pitched and tinkling. A CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis suggested a small bowel obstruction. A clear transition point was identified, associated with a 25cm closed loop segment of small bowel (Figure 1). Additional CT findings were of abnormal and nodular appearance to the omentum and pelvic peritoneum, but normal appearance of the ovaries bilaterally. Ascites was not present.

Figure 1. Small bowel obstruction.

CT scan demonstrating small bowel obstruction with transition point and diffuse peritoneal disease.

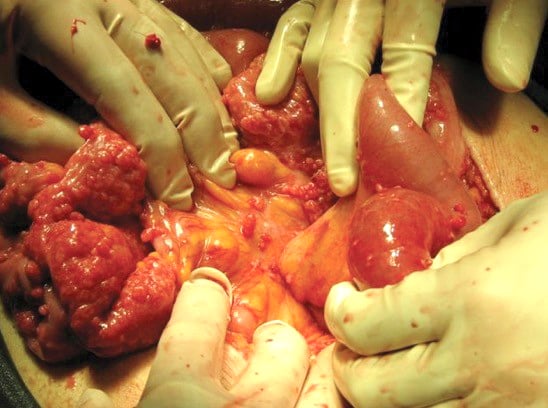

The patient was admitted and underwent a mid-line laparotomy in acute management of small bowel obstruction. Inspection of the abdominal and pelvic peritoneal surfaces and organs revealed innumerable soft tissue implants, each measuring less than 1cm in size. Multiple uterine fibroids were identified and the ovaries appeared macroscopically normal. Particularly involved with tumour were small and large bowel serosa, as well as the recto-sigmoid mesentry (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Disseminated leiomyosis peritoneii. Innumerable smooth muscle tumourlets can be seen scattered across peritoneal surfaces.

The site of the closed-loop small bowel obstruction was clearly identified. The tumour had eroded a 3cm defect in the recto-sigmoid mesentry, through which a loop of small bowel had become incarcerated (Figure 3). A gynaecologic oncologist was invited for intra-operative consultation. Disseminated leiomyomatosis was clinically suspected and supported by frozen section. A 10cm segment of small bowel was resected with functional end-to-end anastomosis, after being reduced through the mesenteric defect. This defect was closed with interrupted sutures.

Figure 3. Internal herniation. Note the recto-sigmoid defect responsible for the closed-loop small bowel obstruction.

Final histologic examination confirmed disseminated leiomyomatosis peritoneii (DLP). The patient’s post-operative progress was poor, featuring persistent pain and prolonged ileus. Total parenteral nutrition was commenced. On day nine post-operatively, the patient demonstrated acute deterioration, with increased pain and tachycardia. CT demonstrated a markedly distended caecum through to descending colon, therefore, the very rare occurrence of a closed loop (mechanical) large bowel obstruction. Emergency operative management was undertaken by a general surgical team who noted extensive leiomyomatous adhesions cicatrising the sigmoid deep in the pelvis. A venting ascending colostomy was performed.

The patient was discussed at a gynae-oncology tumour board meeting and was commenced on a gonadotropin-receptor agonist (Goserelin). She made a slow, but successful, post-operative recovery. Six months from presentation, the patient underwent elective surgical cytoreduction. This procedure involved hours of adhesiolysis, extended hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophrectomy, high anterior resection, ileocolic resection and colostomy reversal. She is now well and is the subject of regular follow up by general surgery and gynaecologic oncology. She has experienced significant menopausal symptoms that have been successfully managed via non-hormonal means.

Discussion

Histologically benign, DLP is a condition featuring multiple smooth muscle tumourlets scattered across peritoneal surfaces. These lesions are both micro- and macroscopically identical to their uterine counterparts (leiomyomata or fibroids). The macroscopic appearance is similar to metastatic ovarian or peritoneal carcinoma and can pose a significant diagnostic dilemma. Histologic examination demonstrates bland smooth cells with low proliferative activity, no significant atypia and no geographic tumour necrosis.1 As seen in our case, intra-operative frozen section and the clinical experience of a gynaecologic oncologist can be beneficial in making the diagnosis.

A rare entity, first described by Wilson and Peale in 1952,2 fewer than 200 cases of DLP have been described. The majority of cases feature an indolent (or benign) clinical course where discovery of the disease is incidental, rarely requires acute management, or is found to invade surrounding structures. Most cases are discovered at the time of surgery performed for an unrelated condition (for example, caesarean section). Locally destructive DLP, as seen in our case, or DLP as the aetiological agent in small or large bowel obstruction, is exceedingly rare.3 The possibility of malignant (or sarcomatous) transformation of DLP (estimated at less than 5 per cent risk) is also rare.

Figure 4. Mechanical large bowel obstruction. CT scan demonstrating a closed loop large bowel obstruction, secondary to extensive leiomyomatous adhesions cicatrizing the rectum and sigmoid.

Most cases of DLP arise in pre-menopausal women. Multiple aetiologic factors have been identified, including transcoelomic metaplasia (as proposed in the development of endometriosis) and hormonal stimulation (pregnancy, oestrogen-secreting tumours, assisted reproductive technologies, long-term contraceptive use). Importantly, intraperitoneal seeding of morcellated benign uterine fibroid tissue has also been implicated.4 5

Treatment options are poorly described and there is no consensus regarding management. The hormonally sensitive nature of the disease necessitates removal of oestrogen exposure, including cessation of hormonal contraceptives, avoidance of hormonal replacement therapy and/or induction of menopause (surgically or via the use of gonadotropin-receptor antagonists). The requirement for acute or cytoreductive surgical intervention is rare, but has been reported in a few cases similar to ours, where the disease has invaded local structures.

Conclusion

Our report describes a case of DLP resulting in significant surgical morbidity, requiring radical surgery.6 7 This case is a clear example of the potential for serious sequelae arising from disseminated benign disease and describes a novel management strategy employing both medical and surgical treatment modalities.

References

- Crum CP, Lee KR, Nucci MR. Diagnostic gynecologic and obstetric pathology. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2011.

- Willson JR, Peale AR. Multiple peritoneal leiomyomas associated with a granulosa-cell tumor of the ovary. AJOG 1952;64(1):204-8.

- Ghosh K, Dorigo O, Bristow R, Berek J. A radical debulking of leiomyomatosis peritonealis disseminata from a colonic obstruction: a case report and review of the literature. Journal of the American College of Surgeons 2000 Aug;191(2):212-5.

- Lete I, González J, Ugarte L, et al. Parasitic leiomyomas: a systematic review. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology 2016 Aug 1;203:250-9.

- Cohen A, Tulandi T. Long-term sequelae of unconfined morcellation during laparoscopic gynecological surgery. Maturitas 2017 Mar 1;97:1-5.

- Ghosh K, Dorigo O, Bristow R, Berek J. A radical debulking of leiomyomatosis peritonealis disseminata from a colonic obstruction: a case report and review of the literature. Journal of the American College of Surgeons 2000 Aug;191(2):212-5.

- Ramos A, Fader AN, Roche KL. Surgical cytoreduction for disseminated benign disease after open power uterine morcellation. Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Jan;125(1):99-102.

Leave a Reply