Metformin is an oral hypoglycaemic medication with a long history. First isolated in 1922, it has been available in Australasia for more than 40 years. Metformin is central to local and international guidelines for the management of type 2 diabetes and has other widening clinical indications. Apart from lowering blood glucose levels, metformin helps combat hypertriglyceridemia, has some vasoactive properties and does not cause weight gain.1

Metformin is usually well tolerated, however, minor side effects such as nausea and diarrhoea are relatively common. The more serious side effect of lactic acidosis is very rare. For many years, metformin was tainted by experience with a related compound, phenformin, which could cause lactic acidosis due to variations in metabolism by the liver. Unlike phenformin, metformin is not metabolised by the liver and is excreted unchanged in the urine.

Treatment of diabetes in pregnancy has traditionally focused on the use of insulin. Australian Diabetes In Pregnancy Society (ADIPS) guidelines (2005) state that insulin is the therapy of choice for gestational diabetes (GDM), citing concerns about lack of evidence for the safety of metformin. However, more recent studies show that metformin, with or without insulin therapy, has several fetal and maternal advantages over insulin therapy alone. It is anticipated that metformin use in GDM and type 2 diabetes in pregnancy will increase, especially if longer term fetal safety, or even benefit, is shown. Other uses of metformin to be considered are in the treatment of insulin resistance syndromes, such as PCOS and prevention of type 2 diabetes following GDM.

Metformin for women with gestational diabetes

The prevalence of GDM is increasing by four per cent annually and already occurs in five to ten per cent of pregnancies. GDM is associated with maternal and fetal complications, such as pre-eclampsia, macrosomia, shoulder dystocia and neonatal hypoglycaemia. GDM also increases the risk of obesity and type 2 diabetes in childhood in the offspring.2 The Australian Carbohydrate Intolerance Study in Pregnant Women (ACHOIS) showed that treatment of GDM with lifestyle modification and insulin, if necessary, is very effective, with the rate of serious perinatal outcomes reduced from four per cent to one per cent.3 The longer term fetal benefit of GDM treatment with insulin is not so clear, with the follow-up study of offspring showing no difference in BMI between groups at four to five years of age.4

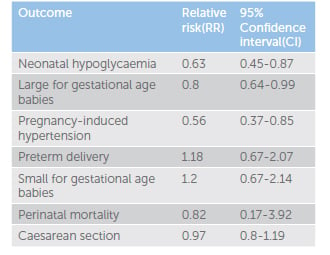

While treatment of GDM has traditionally meant insulin therapy, there has been an increase in the use of oral hypoglycaemic agents as an alternative.5 A recent meta-analysis by Butalia et al of 14 randomised controlled trials (RCT) compared metformin (with or without insulin) with insulin in pregnant women with GDM or type 2 diabetes, and reported maternal or fetal outcomes.6 Eleven studies enrolled women with GDM (n=2062) and three studies enrolled women with type 2 diabetes (n=103). The included studies were from a broad geographical area, including North and South America, Australasia, Europe and the Middle East. The study found that 14 to 46 per cent of women with GDM in the metformin group required the addition of insulin to meet glycaemic targets in pregnancy, indicating that metformin therapy alone is often insufficient. Compared with insulin treatment alone, metformin treatment resulted in lowered risk of hypoglycaemia, large for gestational age babies and pregnancy-induced hypertension. Metformin did not increase preterm delivery, small for gestational age babies, perinatal mortality or caesarean section (see Table 1).

Table 1. Meta-analysis of metformin treatment (with insulin if necessary) versus insulin treatment alone.

The metformin treated group also had reduced maternal total weight gain (mean difference -2.07kg; 95% CI:-2.88 to -1.27). This result is important as rates of obesity are rising in our population. More than 40 per cent of women aged 25–34 in Australia are overweight or obese. The prevalence of severe obesity in Australia has tripled in the past 20 years. Obesity is independently associated with adverse maternal and fetal outcomes, so diabetes management in pregnancy that minimises weight gain is important.

This meta-analysis shows that in the short term metformin, with or without insulin treatment, outperforms insulin alone. The next question is how metformin compares with insulin treatment in the longer term.

Long-term effects of metformin use in pregnancy

A major concern for many considering using metformin in pregnancy relates to some uncertainty regarding the effects of fetal exposure to metformin. Unlike insulin, metformin does cross the placenta, with fetal levels being approximately half the maternal levels.7

When metformin is taken during the first trimester of pregnancy, there is no evidence of an increased risk for major fetal malformation. A meta-analysis of pregnancy outcome after metformin exposure in the first trimester in women with PCOS showed the fetal malformation rate was significantly lower than the disease matched control group (1.7% in metformin group, 7.2% in control group).8

The effect of metformin has been studied in in-vivo mouse models with both positive and negative results. Studies have found in-utero exposure to metformin reduces fetal inflammation and improves metabolic programming. Other studies have raised concerns that metformin may have harmful effects on testicular development; however, a five-year follow-up study after metformin treatment of GDM found no effect on testicular size in male offspring.9

Two studies in the meta-analysis by Butalia et al provide long-term follow-up data to assess the fetal effects of exposure to metformin in-utero.10 One study reported growth and development at six, 12 and 18 months in children born to women with GDM, randomised to either metformin or insulin.11 Children in the metformin group weighed more at 12 and 18 months, and were taller at 18 months compared to the insulin group, but their body composition, defined by mean ponderal index (PI), did not differ.

Rowan et al reported body composition of children two years of age born to women with GDM, randomised to either metformin or insulin.12 Children of mothers in the metformin group had no difference in overall body composition as measured by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) and bioimpedence. Anthropometry suggested these children had more fat stored in subcutaneous depots compared with those in the insulin group, a finding which potentially suggests benefit from metformin treatment.

Overall, the meta-analysis found that metformin in pregnancy had no short-term adverse effects on pregnancy and potential benefits in the neonatal period, but there was limited long-term follow-up information. We await the results of two further follow-up studies, including the Metformin in Gestational Diabetes: The Offspring Follow-Up (MiG TOFU) study on nine-year measures of visceral fat and insulin sensitivity, as well as ongoing trials, such as the Metformin in Women With Type 2 Diabetes in Pregnancy Kids trial (MiTy Kids).

Prevention of type 2 diabetes

Women with GDM have a greater risk of developing diabetes in the future compared with those women who have normal glucose tolerance during pregnancy. In a follow-up trial conducted at Mercy Maternity Hospital, Melbourne, 447 women who had GDM have been retested at intervals of one to 12 years following diagnosis. 49 (11%) were found to be diabetic and 35 (7.8%) had impaired glucose tolerance.13

The Diabetes Prevention Program randomised women who had GDM to standard lifestyle and placebo, metformin therapy or to an intensive lifestyle intervention. The study found that both intensive lifestyle intervention and metformin are highly effective in delaying or preventing the development of diabetes.14 Intensive lifestyle intervention is recommended for all women who have had GDM. Metformin should be considered in women who have difficulty in adapting their lifestyle.

In pregnancy for obese women without GDM

Obesity without GDM is associated with adverse maternal and infant outcomes. As metformin is shown to reduce weight gain and improve insulin sensitivity, its place in managing pregnant women without GDM is of interest. In a double blind placebo-controlled trial, pregnant women without diabetes who had a BMI of more than 35 were randomly assigned to receive metformin, at a dose of 3g per day, or placebo. There was greater reduced maternal weight gain in the metformin group than the placebo group (4.6kg [interquartile range, 1.3 to 7.2] versus 6.3kg [interquartile range, 2.9 to 9.2], p<0.001) but not neonatal birth weight (median neonatal birth weight z score 0.05 in the metformin group [interquartile range, -0.71 to 0.92] and 0.17 in placebo group [interquartile range, -0.62 to 0.89], P=0.66).15 The study concluded that the antenatal administration of metformin among women with a bone mineral density (BMI) greater than 35, but without diabetes, resulted in reduction in maternal weight gain but not neonatal birth weight. This finding mirrors the effect of metformin on maternal weight gain in women with GDM or type 2 diabetes. However, without demonstration of fetal benefit, metformin is unlikely to be indicated for obese women without diabetes in pregnancy.

In pregnancy for women with PCOS

Metformin has been shown to improve insulin resistance and ovulation in patients with PCOS. A randomised placebo-controlled, double blind multicentre study showed metformin treatment from the first trimester until delivery did not reduce pregnancy complications (pre-eclampsia, preterm delivery, GDM or fetal birth weight).16

A small (n=25) RCT of women with PCOS, randomised to metformin or placebo, reported eight-year follow-up data on their children.17 Concerningly, in this very small study, systolic blood pressure and fasting glucose levels were higher in the children of mothers who used metformin. Currently, given the limited data regarding metformin use in pregnant women with PCOS, continuation of metformin in patients with PCOS in pregnancy is not recommended.

In pregnancy for pre-existing type 2 diabetes

The prevalence of type 2 diabetes is increasing and it is strongly associated with obesity. The maternal and fetal risks of pregnancy complicated by type 2 diabetes are similar to risks associated with type 1 diabetes. Women with type 2 diabetes are often treated with metformin prior to pregnancy. To date, there have only been very small intervention trials comparing metformin with insulin treatment during pregnancy, in women with pre-existing type 2 diabetes. A recent Cochrane review concludes that there is insufficient RCT data to evaluate the use of oral anti-diabetic agents in pregnant women with pre-existing diabetes.18 The results of ongoing trials in this area are awaited. The MiTy randomised placebo-controlled trial of metformin versus placebo, examining a composite end-point of early maternal and fetal outcomes, is currently recruiting women with type 2 diabetes at six weeks gestation.

Conclusions

Metformin has been examined in the treatment of GDM in more than 2000 women. The short-term fetal and maternal outcomes favour metformin (with or without insulin) over insulin treatment alone. Metformin does not increase congenital abnormalities, is well tolerated and the risk of serious side effects is very low. Clinical trials in other conditions outside of pregnancy also add weight to the conclusion that metformin is safe and effective. The only unanswered questions are to do with the long-term fetal outcomes for which we await the results of ongoing trials.

As evidence accrues, our preference is not to use metformin universally for GDM. We consider metformin for women whom we think would benefit. Insulin treatment for GDM is very effective, however, the finding that metformin reduces maternal weight gain, compared with insulin, means that metformin should be considered for the growing number of women who are obese. Metformin can also be added to insulin therapy for women with diabetes who are inadequately controlled with insulin alone. Metformin is also an alternative treatment for women who refuse to start insulin.

Type 2 diabetes in pregnancy carries significantly higher risks than GDM, even with optimal treatment with insulin. Evidence regarding the use of metformin for type 2 diabetes in pregnancy is limited and therefore caution must be used. Opinions about whether to continue metformin are divided. Our approach is to continue metformin treatment on the basis that the limited data currently available do not favour insulin treatment over metformin, or vice versa. Emerging evidence supports the safety of metformin in pregnancy. For women with type 2 diabetes in pregnancy, we must continue to strive for treatments that achieve better outcomes than those achieved with insulin treatment alone.

References

- Bailey CJ. Biguanides and NIDDM, Diabetes Care 1992;15:755-72.

- Mitanchez D, Burguet A, Simeoni U. Infants born to mothers with gestational diabetes mellitus: mild neonatal effects, a long-term threat to global health. J Pediatr. 2014 Mar;164(3):445-50.

- Crowther C, et al. Effects of treatment of gestational diabetes mellitus on pregnancy outcome. N Engl J Med 2005;352:2477-2486.

- Gillman MW, Oakey H, Baghurst PA, Volker RE, Robinson JS, Crowther CA. Effects of treatment of gestational diabetes mellitus on obesity in the next generation. Diabetes Care 2010 May; 33(5): 964-8.

- Tieu J, Coat S, Hague W, Middleton P. Oral anti-diabetic agents for women with pre-existing diabetes mellitus/impaired glucose tolerance or previous gestational diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2010, Issue 10.

- Butalia S, Gutierrez L, Lodha A, Aitken E, Zakariasen A, Donovan L. Short and long-term outcomes of metformin compared with insulin alone in pregnancy. Diabet Med. 2017;34(1):27.

- Vanky E, Zahlsen K, Spigset O, Carlsen SM. Placental passage of metformin in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertility Sterility 2005 May; 83(5): 1575-8.

- Gilbert C, Valois M, Korean G. Pregnancy outcome after first-trimester exposure to metformin. Fertility Sterility. 2006;86(3):658.

- Tertti K, Toppari J, Virtanen HE, Sadov S, Ronnemaa T. Metformin treatment does not affect testicular size in offspring born to mothers with gestational diabetes. Rev Diabet Stud. 2016;13(1):59-65.

- Butalia S, Gutierrez L, Lodha A, Aitken E, Zakariasen A, Donovan L. Short and long-term outcomes of metformin compared with insulin alone in pregnancy. Diabet Med. 2017;34(1):27.

- Ijas H, Vaarasmaki M, Saarela T, Keravuo R, Raudaskoski T. A follow-up of a randomised study of metformin and insulin in gestational diabetes mellitus: growth and development of the children at the age of 18 months. BJOG 2014; 122: 994-1000

- Rowan JA, Rush EC, Obolonkin V, Battin M, Wouldes T, Hauge WM. Metformin in gestational diabetes: The offspring follow-up (MiG TOFU): body composition at 2 years of age. Diabetes Care 2011; 34: 2279-2284.

- Grant PT, Oats JN, Beischer NA. The long-term follow-up of women with gestational diabetes. ANZJOG. 1986 Feb; 26 (1): 17-22.

- Aroda VR, Christophi CA, Edelstein SL, et al. Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. The effect of lifestyle intervention and metformin on preventing or delaying diabetes among women with and without gestational diabetes: the Diabetes Prevention Program outcomes study 10-year follow-up. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015 April;100(4):1646-53.

- Syngelaki A, Kypros H, Nicolaides J, Hyer S, et al. Metformin versus placebo in obese pregnant women without diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 2016;374:434-43.

- Vanky E, Stridsklev S, et al. Metformin versus placebo from first trimester to delivery in polycystic ovary syndrome. J clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(12): E488.

- Ro TB, Ludvigsen HV, Carlsen SM, Vanky E. Growth, body composition and metabolic profile of 8-year-old children exposed to metformin in utero. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 2012;72: 570-575

- Tieu J, Coats S, Hague W, Middleton P, Shepherd E. Oral anti-diabetic agents for women with established diabetes/impaired glucose tolerance or previous gestational diabetes planning pregnancy, pregnant women with pre-existing diabetes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Oct 18;10.

Leave a Reply