Women with pre-gestational diabetes represent a high-risk pregnancy group for obstetricians.1 How can this be improved? Technology has changed the care of diabetes significantly in the last decade. Have you heard of insulin pumps, continuous glucose sensors and flash monitors? Obstetricians need to become aware of what is available to help women, especially those pregnant with type 1 diabetes. Insulin pumps are being used to manage type 1 diabetes in over ten per cent of young people,2 and will become increasingly used to manage diabetes in pregnancy. However, insulin pumps are not for patients with gestational diabetes.

What is an insulin pump? It is a device the size of a small mobile phone that usually has a 3ml vial of insulin attached to a cannula inserted in the anterior abdominal wall or buttocks. Most women wear the pump conveniently in their cleavage, or more discreetly, in a pocket or clipped on their waistline. The insulin used is quick-acting and continuously infused into subcutaneous tissue via a small cannula that is changed three times a week. Only one injection every two to three days instead of four to six injections a day – bonus! How does this work? The pump allows the insulin to be delivered at different rates through the day at basal doses for when the patient is not eating. The patient can then give bolus doses at the push of a button whenever they eat. Most patients love this device as it gives them freedom with what and when they can eat. They just need a dietician to teach them how to count carbohydrates. If the blood sugar is too high, a correction dose can be given to achieve a programmed target. If the blood sugar is too low or when the patient is sleeping or exercising, the basal rate can be reduced. All of this is achieved with the push of buttons and no extra needles.

You can imagine how much better the pump is for these women in pregnancy. It is very important to keep sugar levels as close to normal in pregnancy for optimal fetal outcomes, yet avoiding hypoglycaemia in the mother. This can be even harder in the first trimester when the woman is unpredictably vomiting, or in third trimester, when the morning sugar rises because of placental hormones. The pump’s programming can be adjusted to manage all of this, with less risk for hypoglycaemia causing maternal harm or even death.

Figure 1. An insulin pump clipped on a waistband.

Why isn’t everyone using a pump?

Firstly, the literature doesn’t show that women on the pump have better pregnancy outcomes.3 There are a few reasons for this, including the trials using older pump technology and being small studies. Importantly, the good glycaemic control must also begin a few months pre-conception for optimal pregnancy outcomes, not just when the woman realises she is pregnant. Pre-conception counselling is very important for women with diabetes.4 The other main confounder in the literature is the use of HbA1c as the marker of glycaemic control. HbA1c is lower in pregnancy by 0.5 per cent because of increased production of red blood cells and may not reflect better glycaemic control. In the small studies on insulin pumps in pregnancy, HbA1c has not been much different with those using multiple daily injections or the insulin pump.5 However, HbA1c is not ideal for correlating glycaemic control in pregnancy and fetal outcomes. Think simply of gestational diabetes: HbA1c is always low to normal in these patients, but the effect of their blood glucose levels affect the baby. There is increasing evidence that measures of time of glucose in normal range would be the better marker of glycaemic control for effects on baby – we don’t have a simple test for that yet. Future advances in continuous glucose sensing and closed-loop pumps will facilitate this.

Secondly, to have the pump, you hope the patient has top-level health cover. A pump is about $10,000 with health funds covering the entire cost (most funds even allow a patient a new pump every four years when the pump warranty from the company usually expires). The National Diabetes Services Scheme (NDSS) covers most of the cost of the ongoing consumables.

Thirdly, and another reason the pump is not a panacea for diabetes (like a Clexane script for pregnant women to reduce thromboembolism), the patient needs to be educated by an experienced team of endocrinologist, diabetes educator and dietitian who are familiar with managing diabetes in pregnancy. It is important to be ahead of the game keeping up with the increasing insulin resistance as pregnancy progresses. Insulin doses can double or triple at certain times of the day by the third trimester.

What about the pump in special situations in pregnancy or postpartum? It is fabulous. It is even possible to give women steroids, if needed, pre-delivery and adjust the pump rates appropriately without needing an intravenous insulin infusion. For labour, the insulin pump rates go down and again this means the woman is free of an intravenous pole with syringe driver attached (no need for complicated IV insulin infusions, though obviously an experienced endocrinologist still needs to supervise the pump rates). For postpartum, the insulin pump is back at often lower than pre-pregnancy rates and can be reduced further with breastfeeding, so there is less risk for hypoglycaemia and women can safely lose weight. What is there not to love? A cautionary note – patients need to be educated well about pump use and must be diligent in making proactive adjustments. The pump does not work by itself (as yet). Also, hospital staff are not trained to deal with insulin pumps, nor are they likely to be, so the patient and their endocrinologist need to be an effective team.

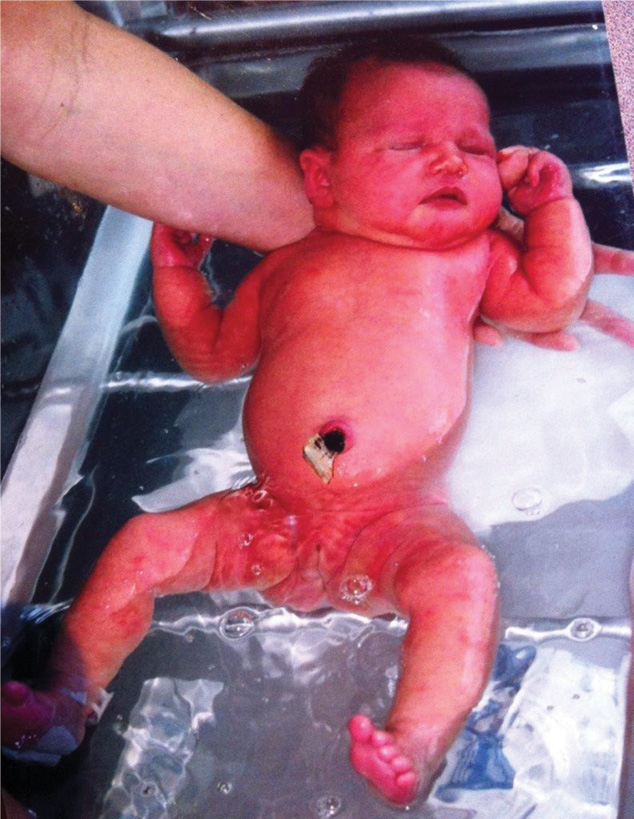

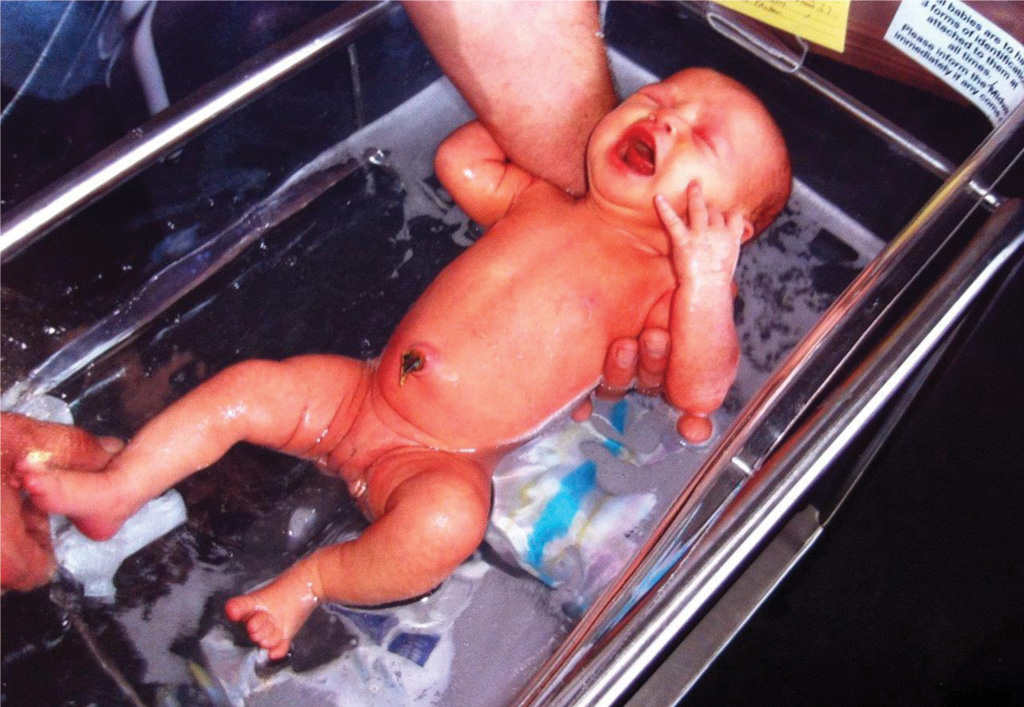

The following photos compare two babies from the same mother with type 1 diabetes – the first pregnancy without an insulin pump and the second pregnancy with an insulin pump. Her second baby did better, even with the mother gaining more weight in that pregnancy.

Figure 2. First baby. The mother had multiple daily insulin injections during the pregnancy.

The woman’s first baby (Figure 2) was delivered by LSCS at 35+ weeks, with a birth weight of 3761g. The delivery was complicated by pre-eclampsia. The mother had a pre-pregnancy BMI of 35.6, gained 16kg in pregnancy and HbA1c 6.8–7.5%.

Figure 3. Second baby. The mother used an insulin pump for this pregnancy.

The woman’s second baby (Figure 3) was delivered by LSCS at 38 weeks, with a birth weight of 3480g. The mother had a pre-pregnancy BMI of 39.4, gained 20kg in pregnancy and HbA1c 5.5-5.6%.

For the motivated patient with a supportive, experienced health team, the insulin pump certainly provides a tool to improve their diabetes control to near-normal range in pregnancy, with less risk for hypoglycaemia and better outcomes for mother and baby. With the coming advances of continuous glucose sensors that either ‘talk’ to the pump or to smart phones, the future is open to achieve the Saint Vincent Declaration (1989), that women with diabetes should have similar healthy pregnancy outcomes as for women without diabetes.6

References

- Outcomes in type 1 diabetic pregnancies. Jensen D, et al. Diabetes Care 2004 27:2819-2823

- www.aihw.gov.au/reports/diabetes/insulin-pump-use-in-australia

- Farrar D, et al. Continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion versus multiple daily injections of insulin for pregnant women with diabetes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016.

- Cyganek K, et al. Glycemic control and selected pregnancy outcomes in type 1 diabetes women on continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion and multiple daily injections: the significance of pregnancy planning. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2010 Jan;12(1): 41-7.

- Farrar D, et al. Continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion versus multiple daily injections of insulin for pregnant women with diabetes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016.

- Diabetes care and research in Europe: the Saint Vincent Declaration. Diabet Med 1990;7:360.

Leave a Reply