Sexual assault is broadly defined as any sexual act carried out against the will of a person through the use of violence, coercion or intimidation.1 Legally, the term sexual assault refers to those cases that involve sexual penetration of the mouth, vagina or anus.2 Sexual assault is very common in Australia. The Australian Bureau of Statistics’ personal safety review in 2012 estimated that one-in-six women and one-in-25 men over the age of 18 have experienced a sexual assault since age 15.3 Rather alarmingly, the incidence of sexual assault in Australia is currently rising, with 2016 data revealing a seven-year high.4

Contrary to popular belief, the majority of perpetrators of sexual assault are known to their victims and a high proportion of perpetrators are current or ex-partners. Stranger assaults only make up approximately 15 per cent of sexual assault cases.5

Given its prevalence, it is important for all clinicians to be confident responding to a disclosure of sexual assault. In most circumstances a clinician will be able to refer such cases to their local Sexual Assault Resource Centre (SARC) for definitive management.

Taking a history

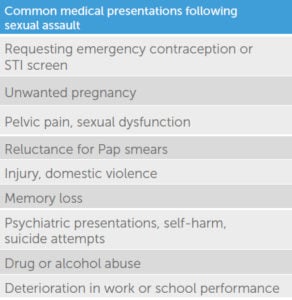

The sexual assault victim may present to you openly and disclose that they have been assaulted. They also might present indirectly. It is important to consider sexual assault when a patient presents with injuries, sexual or mental health problems (Table 1).

Many victims of sexual assault experience self-blame and fear that they will not be believed. Thus, the way in which you respond to a disclosure of sexual assault will not only influence how much distress the patient feels, it will also help determine whether they will report to the police and proceed through the criminal justice system.

Table 1. Common medical presentations following sexual assault.

Ideally, take the history in a private area and do not rush the patient. Take the time to explain confidentiality and its limits, so that the patient is aware that the assault will not be discussed with the police or their family without their consent. One limit to confidentiality is mandatory reporting and it is important to discuss this with the patient prior to assessment. Mandatory reporting laws vary from state to state. In Western Australia, we must report all cases of sexual assault that occur to a person under the age of 18 must be reported.

A good history will gather the information detailed in Table 2. After the history is taken, it is important to discuss the options available to the patient. Some clinicians falsely believe that it is the victim’s responsibility to report to police in order to prevent the perpetrator from committing another assault. However, many patients will not want to report to the police and their choice should be respected.

Table 2. Important features on history.

Assessment and management

There are three key areas to consider: medical, psychosocial and forensic.

1a. Medical issues – contraception

Medical concerns always take priority over a forensic examination. A common concern following female sexual assault victims is that of unwanted pregnancy. It is important to determine if the woman is using reliable contraception and, if not, to offer her appropriate emergency contraception. We predominantly use levonorgestrel; however, ulipristal is now an option to consider, especially for those women presenting more than 72 hours post sexual assault or with a raised BMI.6

1b. Medical issues – STIs

One of the most common concerns following a sexual assault is the risk of acquiring an STI. In the case of a digital assault, we can easily reassure the patient. For the remaining patients, we must provide information about their risk of acquiring an STI; assess the need for prophylaxis and arrange STI screening, taking window periods into account.

I conducted an audit on STI detection at our SARC and found that chlamydia is the most common infection diagnosed. It is not always clear if the infection predated, or was acquired from, the sexual assault. Azithromycin can be offered prophylactically to all victims of sexual assault; however, some clinicians prefer to reserve prophylactic treatment to those patients who are at high risk or unlikely to return for follow up.

We offer prophylaxis against gonorrhoea for cases where we deem the assailant to be high risk. Knowing your local rates of, and risk factors for, gonorrhoea will assist you in deciding whether to provide prophylaxis to your patients.

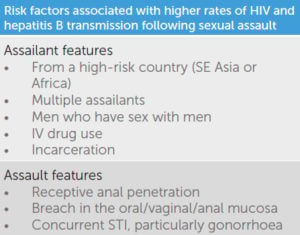

It is uncommon to contract HIV after a sexual assault in Australia. This is because HIV is not easily transmitted through unprotected vaginal sex and because the overall seroprevalence of HIV in Australia is low (0.14 per cent). The risk of HIV transmission after receptive penile-vaginal sex with an HIV-positive male (who is not on antiretroviral treatment) is 1/1250 versus 1/70 after receptive penile-anal sex.7 We offer post-exposure prophylaxis to those patients who present within 72 hours of exposure and either the assailant or the type of assault is deemed to be high risk (Table 3).

Table 3. Risk factors associated with higher rates of HIV and hepatitis B transmission following sexual assault.

Unlike HIV, hepatitis B can easily be transmitted through unprotected penile-vaginal and penile-anal penetration. There is not a great deal of literature regarding post-exposure prophylaxis against hepatitis B. If the patient has been vaccinated against or previously infected with hepatitis B, then they should be immune. We offer a hepatitis B vaccine to anyone who is unlikely to be immune and who presents within two weeks of exposure. Hepatitis B immunoglobulin is reserved for those cases assessed as high risk for hepatitis B transmission (Table 3).8

STI screening is performed at the time of initial presentation and at one month and three months after. Baseline screening is for chlamydia, gonorrhoea, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, HIV and syphilis. If a patient reports a penile-oral or penile-anal assault, one should collect swabs from the oropharynx or rectum. At the one-month follow up we test for chlamydia and gonorrhoea. We can also give the second hepatitis B vaccine if the course was started at the initial presentation. The three-month follow up involves repeating serology and completing the course of hepatitis B vaccination.

1c. Medical issues – injuries

Medical safety of the patient takes priority over any forensic investigation, so it is imperative that you take a history and examine the patient to exclude any significant injuries that need to be managed prior to transfer to SARC. Examples of injuries that need medical review prior to SARC review include head injuries, attempted strangulation, suspected fractures and heavy anogenital bleeding.

2. Psychosocial issues

Following a sexual assault, many people experience suicidal ideation, sleep disturbance, depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder. It is important to perform a risk assessment on all patients following a sexual assault and refer for counselling. Our Perth SARC is happy to offer one-off or regular counselling to people who have experienced a sexual assault.9

Given that many sexual assaults are carried out by a partner, it is important to assess if the patient is safe to return to their accommodation and if the Department of Child Protection needs to be involved to ensure the safety of any children.

3. Forensic issues

The forensic assessment involves documentation of any injuries and collection of specimens to detect DNA and trace evidence. The chance of finding DNA lessens as the time to examination increases so the first clinician to see the patient should collect an early evidence kit (EEK). EEKs are tailored to the type of assault, but may include an oral rinse, first void urine or a gauze wipe of the vulval, penile or peri-anal regions. EEKs are very effective, with a WA SARC study demonstrating that spermatozoa were detected in 35 per cent of EEKs versus 42 per cent of full forensic examinations.10 The clothes worn at the time of the assault should also be collected, with each item in a separate bag. Clothing should still be collected even if it has been washed because DNA may still be obtained. Blood and urine samples should be collected for toxicology assessment if drug facilitated sexual assault is suspected.

A top-to-toe examination should be carried out to look for any general body injuries. It is important to use the correct terminology to document any injuries, namely, bruises, abrasions, lacerations or incised wounds.11 A useful mnemonic to use when documenting injuries is SPICS: site, position, injury type, colour and size. Nearly one-third of patients will have no general body injuries on examination. Approximately one-in-five women have moderate or severe injuries and intimate partners are the most likely perpetrators in these cases (30.4%).12

In Perth, we use naked-eye examination to look for anogenital injuries. An analysis of our database showed that genital injury occurs in 24 per cent of cases of completed vaginal penetration. This is consistent with published data worldwide. Genital injury is more likely if there are multiple penetrants, general body injury is present and if there is no prior history of sexual intercourse (up to 52 per cent). It is less likely to be seen if the victim reports sedation or amnesia or if examination is delayed (most injuries heal within 72 hours).13 Of course genital injuries can also occur during consensual vaginal penetration; however, there is limited published data and the rates tend to be lower.14

A forensic assessment is not a therapeutic examination and hence there are specific consent requirements. It is important to note that in obtaining consent for a forensic examination, duty of care and the mature minor principle do not apply. Assessment of a recent sexual assault is complex, so please do not hesitate to contact your local SARC before commencing a forensic assessment. For Perth clinicians, the WA SARC runs a 24-hour service and we can be contacted on 6458 1828.

References

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Recorded crime – victims, Australia, 2016. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics; 2017.

- Western Australian Police Force (Aus). Criminal Offence Descriptions [Cited Sept 2017]. Available from www.police.wa.gov.au/Crime/Crime-Statistics-Portal/Crime-Statistics-Portal/Criminal-offence-descriptions.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Personal Safety Survey, 2012. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics; 2013.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Recorded crime – victims, Australia, 2016. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics; 2017.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Personal Safety Survey, 2012. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics; 2013.

- Mazza D. Ulipristal acetate: An update for Australian GPs. Australian Family Physician. 2017;46(5):301-4.

- Australasian Society for HIV, Viral Hepatitis and Sexual Health Medicine. Post-Exposure Prophylaxis after Non-Occupational and Occupational exposure to HIV: Australian National Guidelines, 2nd Ed. ASHM, NSW, 2016.

- Australian Government Department of Health. The Australian Immunisation Handbook, 10th Ed, 2017 Update. Chapter 4.5: Hepatitis B. Department of Health, 2017.

- Mason F, Lodrick Z. Psychological consequences of sexual assault. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2013;27(1):27-37.

- Smith DA, Webb LG, Fennel AI, et al. Early evidence kits in sexual assault: an observational study of spermatozoa detection in urine and other forensic specimens. Forensic Sci Med Pathol. 2014;10(3):336-43.

- Sugar NF, Fine DN, Eckert LO. Physical injury after sexual assault: findings of a large case series. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190(1):71-76.

- Zilkens RR, Smith DA, Kelly MC. Sexual Assault and general body injuries: a detailed cross-sectional Australian study of 1163 women. Forensic Sci Int. 2017;279:112-20.

- Zilkens RR, Smith DA, Phillips MA, et al. Genital and anal injuries: A cross-sectional Australian study of 1266 women alleging recent sexual assault. Forensic Sci Int. 2017;275:195-202.

- Sugar NF, Fine DN, Eckert LO. Physical injury after sexual assault: findings of a large case series. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190(1):71-76.

In the state of Victoria (Australia), Sexual Assault does not really need to “involve sexual penetration of the mouth, vagina or anus.” All it needs is touching that is considered sexual and intentional, and despite the accused knowing that the victim did not consent (reference: http://www.furstenberglaw.com.au/sexual-offences/sexual-assault). If sexual penetration occurs, that is Rape or something worse (ex. Sexual Penetration of a Child) and calls for a more severe penalty.