Congenital anomalies of the female genital tract are rare, but important, diagnoses that may present during childhood or adolescence. Abnormalities of the external genitalia, such as common urogenital sinus, cloaca or ambiguous genitalia, tend to be diagnosed at birth or shortly thereafter. These will be managed by a multidisciplinary team of paediatric surgeons, physicians and paediatric gynaecologists. A general practitioner or gynaecologist is more likely to be involved in the diagnosis and care of a Müllerian anomaly; presenting in adolescence with menstrual abnormalities or pain, or during childbearing years with fertility concerns.

Müllerian anomalies occur in approximately 7 per cent of girls1 and result from abnormal fusion or canalisation of the Müllerian ducts. Both environmental and genetic factors are proposed causes, but these have not been proven.2 Current literature does not support the risk of offspring transmission of isolated Müllerian anomalies.3

Development of the reproductive tract

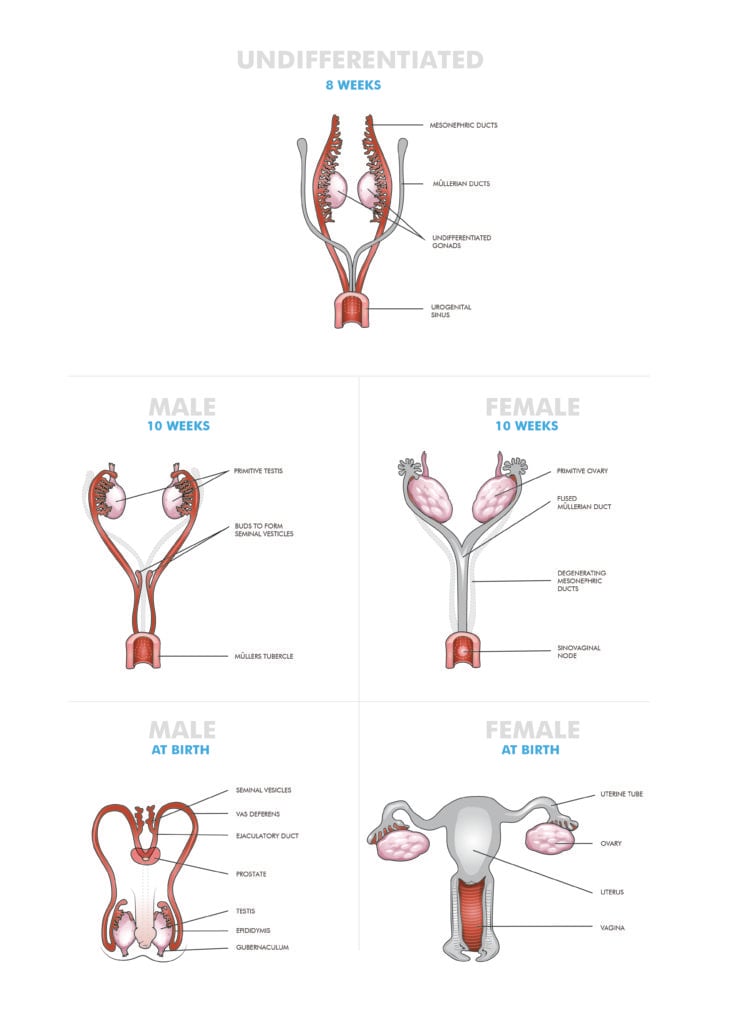

The presence or absence of the sex-determining gene (SRY) on the Y chromosome, leads to differentiation of the indifferent gonad and formation of external genitalia to either a female or male phenotype. When the SRY gene is not present the indifferent gonad forms an ovary and anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH), produced by the fetal testis, is not released. The lack of AMH leads to the development of the Müllerian ducts and regression of the Wollfian (mesonephric) ducts. The Müllerian ducts fuse from approximately six weeks gestation. Once fusion is complete, canalisation occurs to form the uterine cavity. The developing vagina fuses with the urogenital sinus at the vaginal plate (sinovaginal bulb) and then canalises to form the functional vaginal canal by the third trimester. This process results in the upper two thirds of the vagina originating from the Müllerian ducts and the lower third from the urogenital sinus (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Development of the female genital tract.

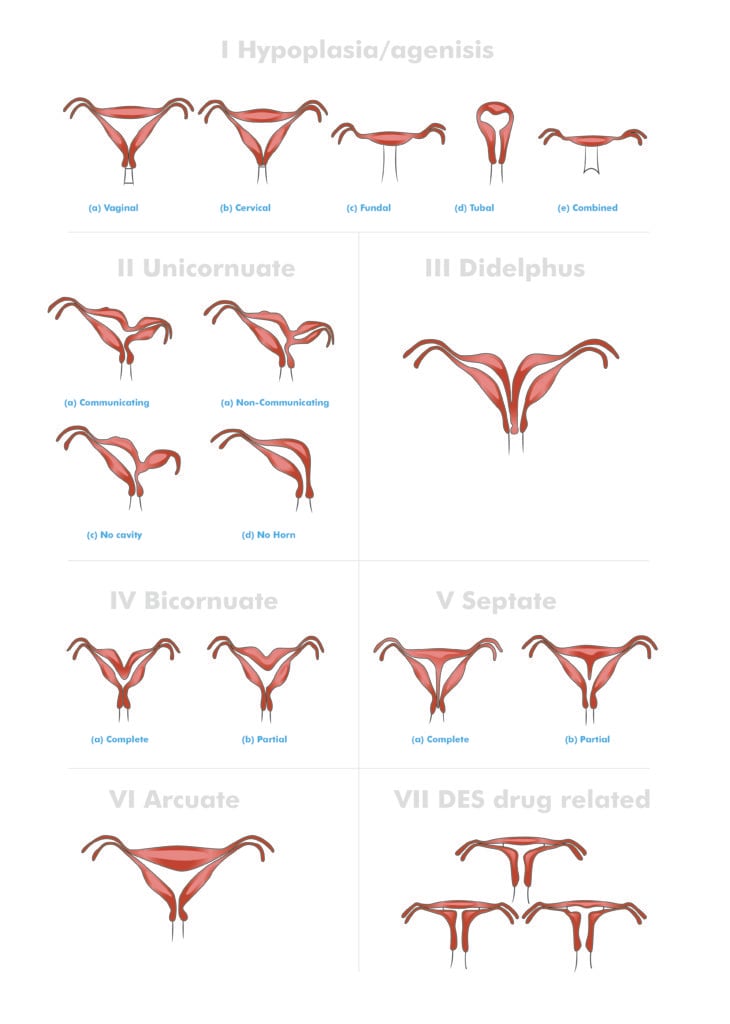

Anomalies of development can occur at any point during the fusion and canalisation process. Due to the wide variation in potential anomalies, multiple classification systems have been developed, with the most commonly used system devised by the American Society of Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) (Figure 2). For clinical purposes, Müllerian anomalies can also be divided into either obstructive or non-obstructive anomalies.

Müllerian anomalies have a high rate of concomitant renal (40 per cent) and spinal (10–20 per cent) anomalies.4 Renal anomalies may include unilateral agenesis, a horseshoe kidney or a pelvic kidney. It is important that assessment for these associated anomalies occur when indicated.

Figure 2. ASRM classification system for mullerian anomalies.

Obstructive anomalies

Obstructive anomalies present in two ways: in adolescents with primary amenorrhoea and cyclical pain, or as progressively worsening dysmenorrhoea with normal menstruation.

Obstruction with primary amenorrhoea and cyclical pain

These anomalies are generally diagnosed in early puberty, after investigation for cyclical pain in the absence of menarche. Due to irregular cycles in adolescence, the pain may not occur monthly, thus diagnosis can be delayed. The outflow tract obstruction leads to a build-up of menstrual blood in the vagina (haematocolpos) or the uterus (haematometra). With a normally functioning uterus and ovaries, this obstruction can occur at any level in the vagina or cervix.

The most common obstructive anomaly is an imperforate hymen, occurring in 1/2000 young women.5 Girls will present with pain secondary to a haematometracolpos. When severe, they may even experience urinary retention or bowel complaints. The mass may be palpable abdominally and vulval inspection will often show a bulging bluish hymenal membrane. This may be diagnosed clinically or confirmed with a pelvic ultrasound.

Transverse vaginal septum is a much rarer condition, occurring in 1/2100–72,000.6 The obstruction can occur at any level along the vagina, most commonly (40 per cent) in the upper third of the vagina.2 The vaginal septum may be thin or thick. More extensive segments of obstructed vagina represent either partial or complete vaginal agenesis. Girls will present in the same manner as an imperforate hymen. However, on examination of the vulva, a normal hymenal opening will be visible without a bulging membrane. Imaging with a pelvic/translabial/rectal ultrasound and MRI are required to assess the extent and location of the transverse septum.

Cervical agenesis or dysgenesis with a normally functioning uterus is a rare condition with an unknown incidence. It will usually present earlier due to pain from the haematometra. Up to 50 per cent will have concomitant vaginal agenesis and 33 per cent have other associated Müllerian anomalies.7 Specialist care and advice is required to determine whether the cervix can be functional in the future, providing potential to maintain fertility.

Obstruction with normal menstruation and worsening dysmenorrhoea

Up to 94 per cent of adolescents experience dysmenorrhoea.8 Most do not have a Müllerian anomaly, but rather have either primary dysmenorrhoea or another cause of secondary dysmenorrhoea. A partially obstructed Müllerian tract should be considered and excluded for girls with worsening symptoms despite conservative treatments (pain medication or cyclical hormonal therapy).9 The most common anomaly is an obstructed hemivagina with complete duplication of the uterus, cervix and upper vagina. Examination may be normal or show an abdominal mass. A digital vaginal examination may be attempted in older/sexually active girls, showing a lateral vaginal mass. Imaging should include a pelvic and renal ultrasound and pelvic MRI.

An obstructed or non-communicating uterine horn will present in a similar fashion as an obstructed hemivagina, but usually at an earlier stage. Examination will show a normal vulva and vagina with a single cervix. Investigation should include a pelvic and renal ultrasound and pelvic MRI.

Management of an obstructive anomaly

Prompt management of an obstructed outflow tract is important due to the risk of endometriosis, pelvic inflammatory disease and haematosalpinx. Hormonal suppression can be instituted while obtaining an accurate diagnosis or if there will be a delay in accessing definitive surgical management. Menstrual suppression is also recommended in cases where pre- or postoperative vaginal dilation will be required, giving time until the child is of an age to undertake the treatment. Suppression options include continuous progesterone (oral/depot), continuous combined oestrogen and progesterone contraceptive pill or gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist. If menstruation is not suppressed, or there is ongoing pain, surgery is indicated.

An imperforate hymen needs to be treated surgically with excision of the hymen under general anaesthesia as an urgent case. Knowledge of the exact location and thickness of a transverse vaginal septum is a vital part of preoperative planning. A thin septum may be excised with direct closure of the vaginal walls, whereas a thick septum or atretic segments may require flaps or skin grafting. There is a significant risk of vaginal stenosis and dilators may be required postoperatively.

An obstructed hemivagina requires surgical excision of the vaginal septum and anastomosis of the vaginal mucosa to close the defect between the two vaginal sections. A non-communicating uterine horn can be removed laparoscopically with good outcomes.

Non-obstructive anomalies

Non-obstructive anomalies of the female genital tract are often asymptomatic and not associated with abnormalities of the external genitalia. A diagnosis may be made when the girl or young woman presents with primary amenorrhoea, dyspareunia, recurrent miscarriage or pregnancy complications.

Uterovaginal agenesis

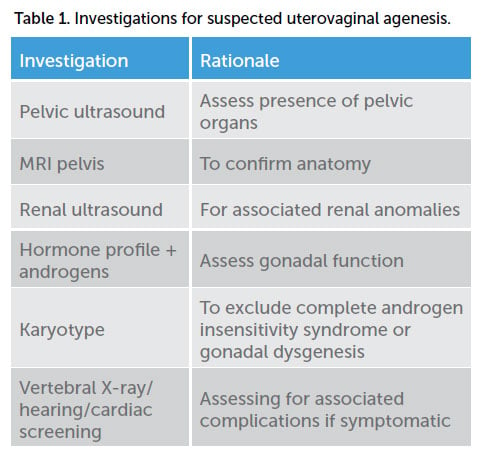

Mayer-Rokitansky-Kuster-Hauser (MRKH) syndrome is uterovaginal agenesis due to failure of the Müllerian ducts to develop. It is a rare condition affecting 1/4500–5000 girls and presents in adolescence with primary amenorrhoea but normal secondary sexual characteristics. A pelvic examination will show normal external genitalia with a normal hymen and a variable length vaginal dimple proximal to the hymen. Investigations should be arranged to confirm the diagnosis and exclude other differentials (Table 1).

The main differential diagnosis for uterovaginal agenesis is complete androgen insensitivity syndrome (CAIS), an X-linked recessive condition affecting the androgen receptor gene resulting in an inability of the tissues to respond to testosterone and dihydrotestosterone, with a prevalence of 1 in 20,000–64,000.10 Girls will be phenotypically female with normal breast development but sparse pubic hair and present with primary amenorrhoea. Due to the 46XY karyotype, the testis will produce normal amounts of AMH resulting in regression of the Müllerian ducts. However, as the tissues do not respond to androgens, female external genitalia will develop and aromatisation of testosterone to oestrogen will result in breast development at puberty. Examination will show a normal vulva with a typically short vaginal dimple proximal to the hymen.

The initial treatment of MRKH and CAIS involves the thoughtful disclosure of the diagnosis to the adolescent and her family and providing appropriate support. Ongoing psychological support from specialists trained in this area can be invaluable. Once the young woman is psychologically ready, further discussion and management can be instituted. The creation of a functional vagina can often be achieved through progressive vaginal dilation, which is considered the first-line option with high success rates (90–92 per cent)11 12 and minimal complications. Dilation is performed daily and can take multiple months to reach a normal size, after which maintenance dilation or regular sexual intercourse is required to maintain the vagina. Surgical neovagina creation is reserved for women who are unable or unsuccessful with vaginal dilation. Many different techniques exist for the creation of a neovagina, including surgically assisted dilation (Vecchietti procedure), vaginoplasty with grafting of split thickness skin or amnion (McIndoe procedure) or pelvic peritoneum (Davydov procedure), intestinal vaginoplasty (commonly using sigmoid colon), or creation of a perineal pouch with skin flaps from the labia.1 No matter which surgical procedure is performed, the woman may need to continue regular dilation or sexual intercourse to maintain the vagina.

A discussion of future fertility should occur when the young woman is ready. Women with MRKH can have biological children through oocyte collection and surrogacy. There is the potential for uterine transplantation in the future; however, this is currently still in research. Women with CAIS will not be able to have biological children, but can still be a parent through surrogacy with donated oocytes or adoption. In addition, there is a risk of gonadal malignancy, which is small during childhood (~5 per cent) and increases during adulthood (~14 per cent), and so discussion of gonadectomy in early adulthood (16–25 years) should occur.13 14

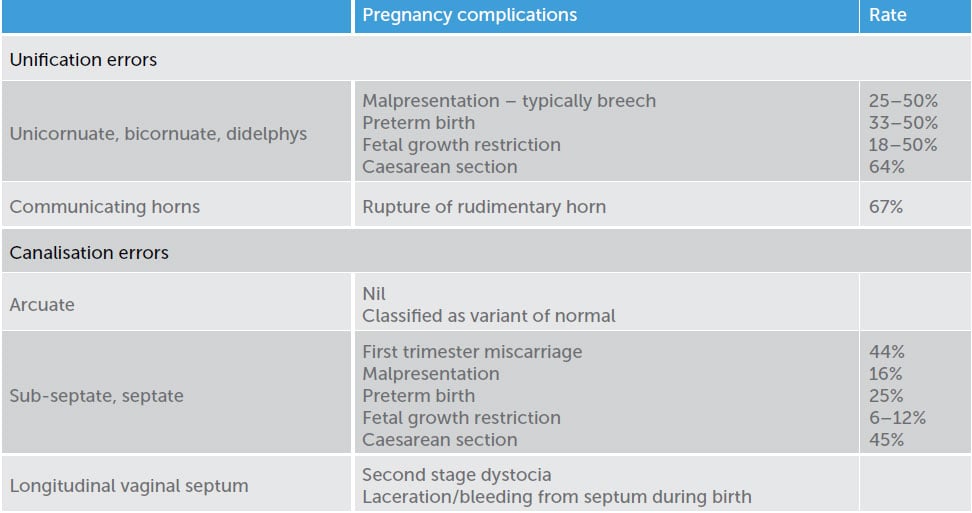

Table 2. Pregnancy complications associated with Müllerian anomalies. 15 16

Longitudinal vaginal septum

Longitudinal vaginal septum occurs as a result of failed fusion of the Müllerian ducts and is typically associated with uterine didelphys due to the failed fusion. Women may present with dyspareunia, leaking when using tampons or be diagnosed at the time of a routine Pap smear. Vaginal septum need only be removed if they are symptomatic or in preparation for an attempted vaginal delivery.

Congenital uterine anomalies

Uterine anomalies occur due to either a unification error (failure of the Müllerian ducts to fuse) or a canalisation error (failure of resorption of the midline fused portion of the Müllerian ducts).17 Variations of uterine anatomy are asymptomatic, but may have the potential to cause pregnancy complications. Table 2 summarises the associations.

Diagnosis of uterine anomalies can be via imaging with hysterosalpingogram (HSG), hystero-contrast-sonography (HyCoSy), MRI or 3D pelvic ultrasound; or via hysteroscopy and laparoscopy to directly visualise the pelvic organs.

Surgical management of septate uteri is controversial, some gynaecologists recommend immediate resection of the septum, while others only resect the septum if complications such as recurrent miscarriage occur. Most women with septate uteri (75–80 per cent) will have normal reproductive function.18

Rudimentary uterine horns are difficult to diagnose, but should be removed due to the high rate of rupture if a pregnancy occurs in the horn.

Conclusion

Congenital anomalies of the female genital tract are rare, but important, diagnoses in the adolescent population. Young women may be asymptomatic or present with primary amenorrhoea, signs of obstructed menstruation, dyspareunia or fertility issues. A thorough history, examination and appropriate investigations are critical before planning definitive management so that the appropriate procedure and expertise are available. Obstructed menstruation should to be treated urgently by either medical or surgical means to prevent future complications, such as endometriosis or infection. A diagnosis of MRKH or CAIS requires careful disclosure in a sensitive manner with appropriate psychological support. Many of these women can attain a functional vagina through progressive vaginal dilation, with only a few women requiring surgical management. Uterine Müllerian anomalies are associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes, including first trimester miscarriage, preterm birth, malpresentation, fetal growth restriction and caesarean section. Young women with congenital anomalies of the genital tract should be cared for in a specialised multidisciplinary team with surgical, medical and psychological expertise.

References

- Dietrich JE, Millar DM, Quint EH. Non-obstructive Müllerian Anomalies. Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology. 2014;27:386-95.

- Dietrich JE, Millar DM, Quint EH. Non-obstructive Müllerian Anomalies. Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology. 2014;27:386-95.

- Dietrich JE, Millar DM, Quint EH. Obstructive Reproductive Tract Anomalies. Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology. 2014;27:396-402.

- Dietrich JE, Millar DM, Quint EH. Obstructive Reproductive Tract Anomalies. Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology. 2014;27:396-402.

- Dietrich JE, Millar DM, Quint EH. Obstructive Reproductive Tract Anomalies. Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology. 2014;27:396-402.

- Dietrich JE, Millar DM, Quint EH. Obstructive Reproductive Tract Anomalies. Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology. 2014;27:396-402.

- Dietrich JE, Millar DM, Quint EH. Obstructive Reproductive Tract Anomalies. Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology. 2014;27:396-402.

- Parker MA, Sneddon AE, Arbon P. The menstrual disorder of teenagers (MDOT) study: determining typical menstrual patterns and menstrual disturbance in a large population-based study of Australian teenagers. BJOG. 2010;117(2):185-92.

- Dietrich JE, Millar DM, Quint EH. Obstructive Reproductive Tract Anomalies. Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology. 2014;27:396-402.

- Mendoza N, Rodriguez-Alcala C, Motos MA, Salamanca A. Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome: An update on the Management of Adolescents and Young People. Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology. 2017;30:2-8.

- Dietrich JE, Millar DM, Quint EH. Non-obstructive Müllerian Anomalies. Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology. 2014;27:386-95.

- Mendoza N, Rodriguez-Alcala C, Motos MA, Salamanca A. Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome: An update on the Management of Adolescents and Young People. Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology. 2017;30:2-8.

- Mendoza N, Rodriguez-Alcala C, Motos MA, Salamanca A. Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome: An update on the Management of Adolescents and Young People. Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology. 2017;30:2-8.

- Deans R, Creighton SM, Liao L-M, Conway GS. Timing of gonadectomy in adult women with complete androgen insensitivity syndrome (CAIS): patient preferences and clinical evidence. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2012;76(6):894-98.

- Dietrich JE, Millar DM, Quint EH. Non-obstructive Müllerian Anomalies. Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology. 2014;27:386-95.

- Fox NS, Roman AS, Stern EM, et al. Type of congenital uterine anomaly and adverse pregnancy outcomes. Journal of maternal-fetal and neonatal medicine. 2014;17(9):949-53.

- Deans R, Creighton SM, Liao L-M, Conway GS. Timing of gonadectomy in adult women with complete androgen insensitivity syndrome (CAIS): patient preferences and clinical evidence. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2012;76(6):894-98.

- Dietrich JE, Millar DM, Quint EH. Non-obstructive Müllerian Anomalies. Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology. 2014;27:386-95.

Leave a Reply