The WHO defines sexual health as, ‘a state of physical, emotional, mental, and social wellbeing in relation to sexuality; it is not merely the absence of disease, dysfunction, or infirmity.’1 It is helpful to keep this definition in mind when discussing sexual health for young people, so that their right to wellbeing is the focus, rather than merely the presence or absence of disease.

Young people are both biologically and cognitively susceptible to acquiring STIs and this is reflected in the higher infection rates seen in those aged less than 25 years in New Zealand (NZ)2 and Australia.3 Research that seeks to understand the resilience factors associated with reducing STI risk behaviour, such as delaying the start of sex, using condoms and limiting the number of sexual partners, hypothesises that behaviour change may be related to improving protective factors for young people. Thus, the increase in NZ secondary school students delaying initiation of sexual behaviour compared to a decade ago may be related to the reported improvement in protective factors over the same time period, such as stronger family and school connections.4 Consistent condom use among Māori males in NZ was associated with good family relationships.5 Such findings indicate the importance of the wider determinants of sexual health and support the need for comprehensive psychosocial assessments, such as HEADSSS,6 that identify risk and protective factors in order to improve sexual health outcomes for our patients.

Good sexual health consultations for our adolescent patients are rewarding. A non-judgemental and collaborative approach is helpful and it is important to be aware of the following key components for consultations involving young people.

Negotiate to see the young person alone

Privacy and confidentiality are crucial components for healthcare consultations involving young people. Informing young people of the right to privacy for their healthcare information will result in more honest sharing of information and greater participation in follow-up care.7

Yet, while the importance of this is acknowledged in guidelines,8 young people tell us it isn’t happening for them. A NZ secondary school survey noted that while 83 per cent of students had accessed healthcare within the preceding 12 months, only 27 per cent of them reported receiving both private and confidential healthcare. Furthermore, students were less likely to receive private and confidential healthcare in settings such as hospital emergency departments compared to school clinics and sexual health clinics.9

Making it your routine practice to see young people on their own for part of most consultations can be helped by the following tips:

- Outline the plan for the consultation at the beginning and explain that after an initial discussion, you will spend some time alone with the young person before regrouping to discuss what comes next.

- Spell out the rules around confidentiality before separating so that both the young person and the parent/guardian(s) are clear that while all people have a right to privacy around their health information, any disclosures involving harm from others, harm to self or harm to others will need to be discussed further and likely involve other parties to ensure safety. Practice this until it feels natural and reflects your own style.

- Listen and acknowledge any parental concerns before separating and at the end of your time alone with the young person agree on what will be discussed with their parent/guardian(s), identifying if any areas are off limits.

Taking a sexual health history with adolescents

Spend some time with the young person establishing a rapport. When asking about sexual activity, it is often helpful to provide a rationale for your questions; for example, ‘these symptoms can sometimes be caused by an STI like chlamydia. Can I ask you some questions to see if you are at risk of that?’ Be calm and demonstrate comfort in discussing the topic.

Establish whether any sexual activity is taking place. Sometimes young people can be at risk of acquiring infections without having penetrative sex; for example, when very close genital-to-genital skin contact occurs, so it can help to explain this.

Be aware that exploring gender and sexual identity is all part of a healthy development; the array of possible combinations is limitless and can be fluid and change over time. Thus, do not presume anything – don’t ask about boyfriends, but instead ask whether they are attracted to males, females or both and about their sexual partners. Do ask the age of sexual partners and how they met, including online. Ask about symptoms, including a recent change in vaginal discharge, vulval or genital skin problems, dysuria, lower abdominal pain, changes in menstrual cycle, irregular bleeding or postcoital bleeding. Explain that it is important to know what sexual contact is occurring to guide sexual health testing.

Discuss with young people that sexual activity should be pleasurable and they should not feel pressured or find the experience unpleasant. Do ask if there has ever been any non-consensual sexual contact; for example, ‘have you ever been touched in a sexual way that you didn’t want’. Be prepared for a disclosure – acknowledge the bravery in disclosing, validate that what happened was not okay and that it wasn’t their fault. If a recent sexual assault is disclosed, be mindful of the need to preserve forensic evidence and consult urgently with specialist sexual assault services. Consider child protection issues and mandatory reporting requirements in your jurisdiction. Know your local referral pathways and be prepared to consult.

Sexual health testing

A full genital examination is important to evaluate a symptomatic patient. This includes using a good light source to examine the genital skin and palpate for inguinal lymphadenopathy. A speculum examination is required if symptoms of vaginal discharge, abnormal bleeding or pelvic pain are present. In addition, a bimanual examination is indicated if pain is present.

A low threshold of suspicion for pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) is important, as the severity of symptoms can vary. New onset of pelvic pain in a young woman is highly predictive of PID, provided surgical emergencies are excluded.10 The diagnosis is clinical and treatment should not be delayed.

Vaginal swabs are more sensitive than urine samples for diagnosing infections in females11 and most laboratories now use multiplex NAAT platforms to diagnose chlamydia, gonorrhoea and trichomoniasis. Be aware that false-positive results for gonorrhoea are possible using NAAT tests in low prevalence populations.12 If taking a swab to culture gonorrhoea, an endocervical swab is required. High vaginal culture swabs are still required to diagnose bacterial vaginosis, candida and trichomonas if no NAAT test is available. Check with your local laboratory to see which tests are available. For young women who are asymptomatic or decline examination, a self-collected vulvovaginal swab to test for chlamydia and gonorrhoea (and possibly trichomonas, depending on local prevalence) is the preferred method for female screening and has been shown to be acceptable.13

Genital herpes is under-recognised as minor lesions are common. Consider a viral swab for any recurring localised anogenital lesions. HSV-1 has been increasingly associated with genital infection, particularly among younger women.14 For patients with lesions suggestive of a first episode of genital herpes, oral antiviral treatment should always be given, regardless of the time of symptom onset. Treat with oral valaciclovir 500mg twice daily for seven days and provide supportive care, including topical anaesthetic creams and advice on salt water bathing.15 16 The NZ Herpes Foundation website provides excellent information for the public and professionals.17 Genital warts are diagnosed clinically; however, significant decreases of 83.4 per cent18 and 92.6 per cent19 in genital warts diagnoses for young women in NZ and Australia, respectively, have been seen five years into the quadrivalent HPV vaccination programs of both countries.

Offer blood tests for HIV, syphilis and hepatitis B. Universal vaccination for hepatitis B has reduced the risk of this infection, but young people born elsewhere may be at increased risk. Be aware that syphilis and HIV rates are rising, resulting in increased risks overall. Offer a test for hepatitis C if there is a history of injecting drug use.

Establish how results will be given and ensure contact details are accurate. Repeat infections following a diagnosis of a bacterial STI are common and retesting three months post-treatment is recommended.20 NAAT testing should not be performed any sooner than approximately one month post-infection as residual DNA may persist despite adequate treatment.21 Educate about negotiating safe sex, how to use condoms and risk minimisation. When appropriate, address contraception needs.

Positive results

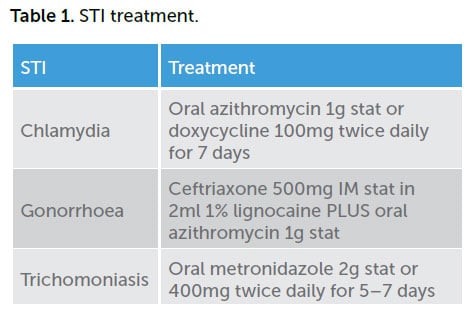

The NZ Sexual Health Society Best Practice Guidelines22 and Australian STI Management guidelines23 provide up-to-date treatment information.

Chlamydia is still the most common bacterial STI, with the highest rates seen in 15- to 19-year-old girls (4774 and 2069 per 100,000 for NZ and Australia, respectively, 2014),24 25 with both countries reporting a steady decline in rates for this group since 2010. Testing rates are high in NZ, with 34.5 per cent of 15 to 19-year-old girls having a chlamydia test in 2014.26

Gonorrhoea rates for 15- to 19-year-old girls in 2014 were 383 and 144 per 100,000 for NZ and Australia, respectively.27 28 Because of concerns regarding emerging antibiotic resistance, dual antibiotic treatment for gonorrhoea is now recommended.

Supporting contact tracing

Providing antibiotics to treat a bacterial STI is only the first part of successful treatment. Unless sexual contacts are treated at the same time, the risk of reinfection from an untreated partner is high, so partner notification is an essential part of STI management. It is your role to encourage and support your patient to notify their contacts.

Identify how many sexual contacts in the past two months for gonorrhoea, or six months for chlamydia. Check Australian STI management guidelines or NZ sexual health guidelines for advice on the recommended look-back period for each infection. Contact tracing is not required for diagnoses of herpes or genital warts.

Check how many of the sexual contacts are contactable and discuss the preferred method of partner notification (face-to-face, texting, phone). Be mindful of any potential risk of violence for young people; sexual health clinics can provide support for contact tracing if needed.

Many young people will prefer to talk to their sexual contacts in person and providing tips can increase their confidence; for example ‘don’t put off talking to sexual contacts as the longer you delay the harder it gets’ and ‘most people find talking to their contacts easier than they thought it was going to be’. Encourage young people to plan what they are going to say. Role playing can help confidence, ‘my doctor just told me my chlamydia test was positive, so that means you might be at risk. You need to go and have a check up and get some treatment.’ This can help avoid inflammatory statements such as ‘you gave me chlamydia!’ It helps to provide written information on the infection diagnosed, highlighting important information, such as that many people with infections have no symptoms.

Follow up with your patient, either in person or by telephone conversation, a week later to ascertain that treatment was taken correctly, that your patient abstained from sex for a week following their treatment and that no sexual contact occurred with an untreated contact. Lastly, enjoy your adolescent patients, providing good health experiences for young people and improving their health literacy is hugely satisfying.

References

- WHO. Defining sexual health: report of a technical consultation on sexual health. Geneva, 2006. Available from: www.who.int/reproductivehealth/topics2006

- The Institute of Environmental Science and Research Ltd. Sexually Transmitted Infections in New Zealand: Annual Surveillance Report. 2014. Porirua, New Zealand.

- The Kirby Institute. HIV, viral hepatitis and sexually transmissible infections in Australia Annual Surveillance Report. 2016. The Kirby Institute, UNSW, Sydney.

- Clark TC, Lucassen MFG, Fleming T, et al. Changes in the sexual health behaviours of New Zealand school students, 2001-2012: findings from a national survey series. Aust NZ J Public Health. 2016;40:329-36.

- Clark TC, Crengle S, Sheridan J, et al. Factors associated with consistent contraception and condom use among Māori secondary school students in New Zealand. J Paediatr Child Health. 2014;50:258-65.

- Goldenring DA, AdelmanJM. HEEADSSS 3.0: the psychosocial interview for adolescents updated for a new century fueled by media. Contemp Pediatr. 2014:1-16.

- Denny S, Farrant B, Cosgriff J, et al. Access to Private and Confidential Health Care Among Secondary School Students in New Zealand. J Adol Health. 2012;52(3):285-91.

- Rogstad K, Thomas A, Williams O, et al. United Kingdom National Guideline on the management of sexually transmitted infections and related conditions in children and young people. 2010. Clinical Effectiveness Group, British Association for Sexual Health and HIV.

- Denny S, Farrant B, Cosgriff J, et al. Access to Private and Confidential Health Care Among Secondary School Students in New Zealand. J Adol Health. 2012;52(3):285-91.

- Australian STI Management Guidelines. www.sti.guidelines.org.au.

- Wangu Z, Burstein GR. Adolescent sexuality updates to the sexually transmitted infection guidelines. Pediatr Clin N Am. 2017;64:389-411.

- The New Zealand Sexual Health Society Incorporated. Best Practice Guidelines. www.nzshs.org/guidelines

- Wangu Z, Burstein GR. Adolescent sexuality updates to the sexually transmitted infection guidelines. Pediatr Clin N Am. 2017;64:389-411.

- Gray E, Morgan J, Linderman J. Herpes simplex type 1 versus Herpes simplex type 2 in anogenital herpes; a 10-year study from the Waikato region of New Zealand. NZ Med J. 2008;121(1271):43-50.

- Australian STI Management Guidelines. www.sti.guidelines.org.au.

- The New Zealand Sexual Health Society Incorporated. Best Practice Guidelines. www.nzshs.org/guidelines

- The New Zealand Herpes Foundation. www.herpes.org.nz.

- Oliphant J, Stewart J, Saxton P, et al. Trends in genital warts diagnoses in New Zealand five years following the quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine introduction. NZ Med J. 2017;130(1452):9-16.

- Ali H, Donovan B, Wand H, et al. Genital warts in young Australians five years into national human papillomavirus vaccination programme: national surveillance data. BMJ. 2013;346:2032.

- The New Zealand Sexual Health Society Incorporated. Best Practice Guidelines. www.nzshs.org/guidelines

- Wangu Z, Burstein GR. Adolescent sexuality updates to the sexually transmitted infection guidelines. Pediatr Clin N Am. 2017;64:389-411.

- The New Zealand Sexual Health Society Incorporated. Best Practice Guidelines. www.nzshs.org/guidelines

- Australian STI Management Guidelines. www.sti.guidelines.org.au.

- The Institute of Environmental Science and Research Ltd. Sexually Transmitted Infections in New Zealand: Annual Surveillance Report. 2014. Porirua, New Zealand.

- The Kirby Institute. HIV, viral hepatitis and sexually transmissible infections in Australia Annual Surveillance Report. 2016. The Kirby Institute, UNSW, Sydney.

- The Institute of Environmental Science and Research Ltd. Sexually Transmitted Infections in New Zealand: Annual Surveillance Report. 2014. Porirua, New Zealand.

- The Institute of Environmental Science and Research Ltd. Sexually Transmitted Infections in New Zealand: Annual Surveillance Report. 2014. Porirua, New Zealand.

- The Kirby Institute. HIV, viral hepatitis and sexually transmissible infections in Australia Annual Surveillance Report. 2016. The Kirby Institute, UNSW, Sydney.

Leave a Reply