Chronic pelvic and sexual pain in women is associated with significant morbidity and financial cost to the individual as well as their partners, families and the wider community. Chronic pelvic pain (CPP) is estimated to affect 15 per cent of women aged 18–50 years.2 There is a complex interplay of biological, behavioural, environmental and societal factors compounded by complex neurogenic innervation of closely related visceral and somatic structures, by the intimate nature of the area and impact on personal relationships and sexuality. Epidemiologic studies reveal a high community prevalence of chronic pelvic pain in women of reproductive age, with reported rates of 14.7 per cent in the US.1

Once a diagnosis of possible pelvic floor dysfunction as a contribution to chronic pelvic pain is made, objective measurements and physiotherapy as a method of low-risk treatment is a logical, inexpensive and nonsurgical approach to treatment.2 Of patients with chronic pelvic pain, 85 per cent present with dysfunction or impairments of the musculoskeletal system – for example, poor posture and pelvic floor muscle imbalances.3

Pelvic floor muscle (PFM) pain and increased tension are commonly associated with pelvic, vulval and sexual pain presentations, and are emerging reasons for referral to pelvic floor physiotherapy. The addition of biofeedback provides the patient with objective information regarding the adequacy of pelvic floor training and objective assessment of changes in the baseline tone and strength for the physician.4 The relationship between the symptom of PFM pain and the sign of altered PFM tension is not well understood, but co-occurrence is frequently observed with causality difficult to prove. These ‘tissue-focused’ interventions play an important role; however, there is strong evidence for a biopsychosocial approach to management of persistent pelvic floor muscle pain, owing to the high prevalence of contributing psychological variables. Both peripheral and central abnormalities have been implicated in vulvar/sexual pain, indicating central hypersensitivity and therefore an inherent need to address central nervous system dysfunction.

Classification

CPP is chronic or persistent pain perceived in the structures related to the pelvis. It is often associated with negative cognitive, behavioural, sexual or emotional consequences as well as with symptoms suggestive of lower urinary tract, sexual, bowel, pelvic floor or gynaecological dysfunction.5

The European Association of Urology (EAU), in its 132-page guidelines on CPP, describes various visceral and somatic CPP syndromes according to phenotyping, terminology and taxonomy. The focus is on defining the end-organ dysfunction; a process that is useful for identification of the tissue that may be the primary pain generator in peripheral dysfunction. While useful as a classification schema, a limitation is the frequently observed overlap of many of these diagnoses.6

From classification of terminology, to describing the distinguishing features of a condition or syndrome, we can then model treatment effects, based on what we understand is the target tissue of our intervention.

While it is good that a muscular pain syndrome has entered this nomenclature, it doesn’t really fit as a urogenital pain syndrome. Somatic pain is known to be quite different from visceral pain and within somatic pain there are differences, such as cutaneous pain versus muscle pain. Much is known about cutaneous sensation, but little is known of muscle pain, or myalgia, in the pelvis. While this table suggests discrete entities of CPP, many of these CPP conditions overlap and co-exist, due to factors such as the complexities of visceral-somatic innervation and neural cross-talk.

Interestingly, PFM pain syndrome is not further defined along this axial system in the table, which suggests much less is understood of it, compared with bladder pain syndrome, pelvic pain syndrome and vulvodynia.

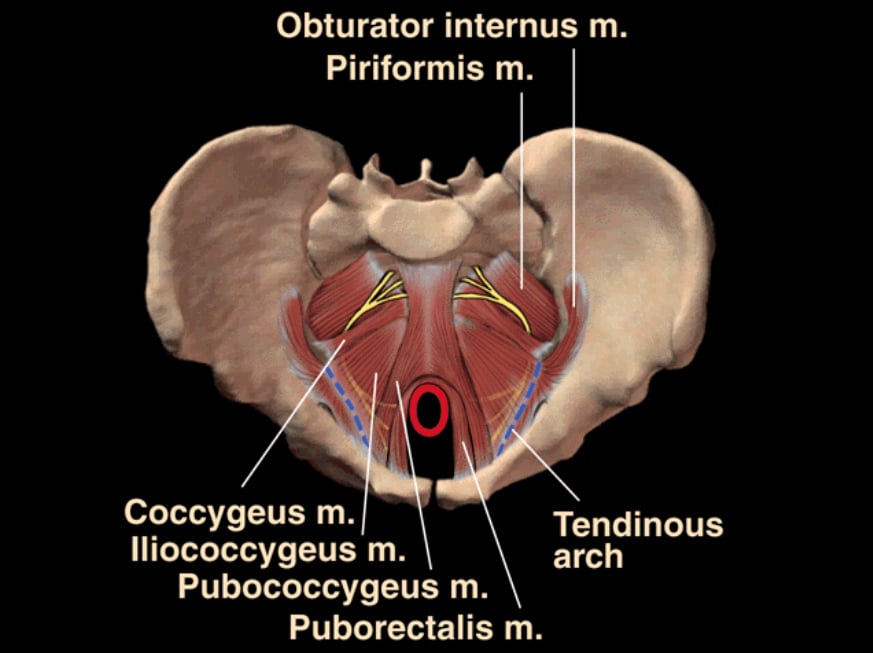

Figure 1. Anatomical illustration of pelvic floor muscles to examine when assessing pelvic floor spasm.

Subjective assessment

Diagnostic and narrative-oriented assessments and clinical reasoning occur simultaneously and each influences the other.

Diagnostic reasoning: biomedically oriented assessment and analysis. This looks at physical impairments, pain mechanisms and pain behaviour, structures and pain sources and pathologies, O&G history, bladder and bowel symptoms in addition to exploring pain with coitus. It explores physical and biomechanical contributing factors, such as other musculoskeletal and neurological factors.

Narrative reasoning: psychosocially oriented assessment and analysis. This is about understanding the patient as a person, their personal story or narrative, their perspectives of their disability/pain experience. It is important to understand beliefs, attributions, coping, emotions, sense of self and future projections.

Collaborative reasoning: is used by expert clinicians. It is a consensual approach to interpretation of results, setting of goals and implementation of treatment. Collaboration leads to ‘mutual construction of meaning’ that places a high value on a patient’s insights into their problem. A transfer of knowledge from the health professional to patient and a shift of power toward the patient then occurs, which reduces distorted perspectives of their situation.

Objective assessment

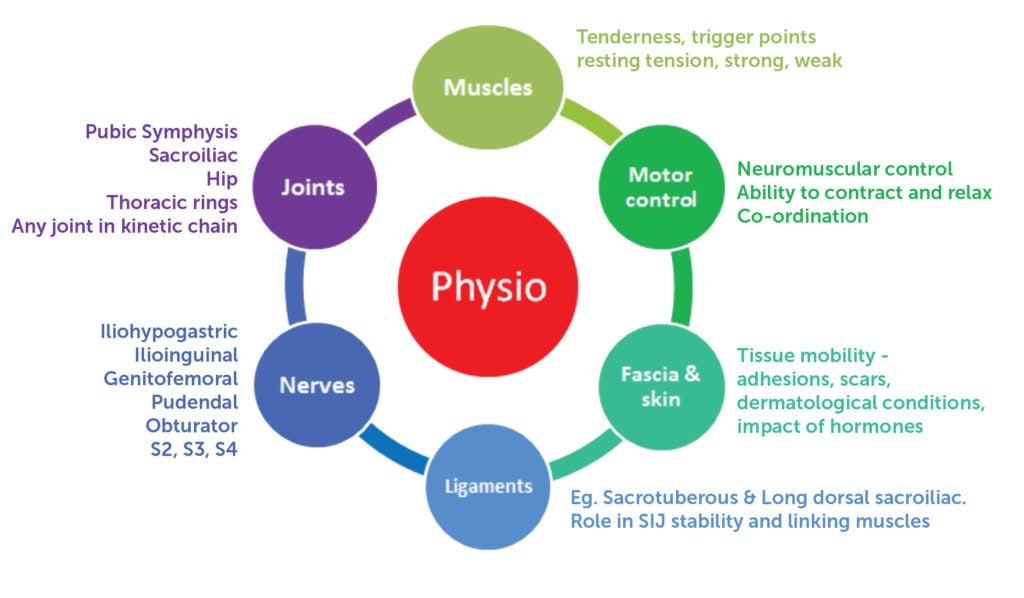

Objective assessment (for pelvic pain) will incorporate assessment and testing of a range of pelvic muscles, joints, nerves, ligaments, fascia and skin.

Pelvic floor muscle tension/stiffness

It has been suggested that pelvic floor hypertonicity is the factor that may connect certain urological, urogynaecological, ano-rectal and gastro-intestinal conditions with sexual dysfunction and pain.7 We have known for many years that pelvic floor hypertonus is a component of conditions such as constpation, anismus, irritable bowel syndrome and proctalgia fugax. Patients with dyssynergia tend to empty their bladder by pushing or straining rather than gently releasing their PFM.

A discussion has emerged in the literature regarding the hypertonic pelvic floor and its relationship to CPP, especially sexual pain conditions. Pelvic floor pathophysiology in vaginismus, dyspareunia and pelvic pain is commonly hypertonicity.8 In a Canadian study, 90 per cent of women with vulvo-vaginal dysfunction had pelvic floor dysfunction.9 Pelvic floor pathology is likely to play a significant role in the maintenance and exacerbation of sexual pain via reactive muscle guarding, tissue restriction due to hypertonicity and lack of vaginal muscle control. Increased passive and active tension in the PFM leads to tissue ischemia and irritation of the pelvic nerves.

Assessing the pelvic floor muscles

History and physical examination underpins diagnosis and treatment of chronic pelvic pain. Gynaecologists are familiar with assessment and treatment of pelvic floor laxity, but have very limited knowledge in the assessment and treatment of pelvic floor spasm, tension, tone and pain for gynaecological symptoms.10 Pelvic examination to investigate acute or chronic pelvic pain should always include single-digit palpation of at least the perineals, levator ani, piriformis and obturator internus muscles.

Begin by palpating the introitus to rule out vaginismus. Examine the hymenal remnant very gently, and make sure it is not causing pain. If not, then directly beneath the hymenal remnant is the bulbospongiosis (Figure 3), most often tender at 3 o’clock and 9 o’clock. Push at these points firmly and steadily. Then move internally and examine pubococcygeus from attachment to insertion, paying special attention to 4 o’clock and 8 o’clock which is where most commonly there are muscle trigger points.6 Spasm of a portion of the levator ani is often detected as a palpable band resembling a guitar string within the muscle or a focal trigger point. To examine for piriformis, press posterolaterally and superiorly to the ischial spine.11 Then use your left hand to examine for the left obturator internus, getting the patient to push their left knee into your right hand to put the muscle under tension and reverse the hands for the other side. Each time you examine an area ask if it reproduces the pain the patient experiences. Ask the patient to contract the pelvic floor muscle then relax the muscle. Often they do not move the muscle at all as the resting tension is so high. Another typical finding during examination is a distinct asymmetry between the right and left elements of the pelvic diaphragm. This shortening or contracture will usually be ipsilateral to the patient’s pain.

Figure 2. EAU classification of chronic pain syndromes.

Figure 3. Examination of the bulbospongiosis.

Best-practice management

It is essential that women with chronic pelvic and sexual pain are treated by a multidisciplinary team of healthcare professionals to enable a thorough assessment and an individualised treatment plan. This team will often include a gynaecologist, pelvic floor physiotherapist, a psychologist, and sometimes a pain medicine specialist. Pelvic floor physiotherapy management is multi-modal, involving a combination of ‘hands off and hands on’ therapy.12 Treatment of the pelvic floor muscle dysfunction involves manual techniques such as stretching and internal myofascial release to reduce muscle tension and treat trigger points. Depending on the referral pattern, these techniques can also be applied to piriformis, obturator internus, adductors and abdominals.

A PFM exercise program incorporating biofeedback aims to promote relaxation, control, strength, speed and endurance of contraction. This is performed as a daily home exercise program, often supplemented with the use of a home trainer program for tissue mobilisation and desensitisation.

Pelvic floor physiotherapy also involves a significant educational component including the science of chronic pelvic pain. Pain is an output of the brain, it is altered by thoughts, emotions and attitudes. The level of pain a person perceives is closely related to the level of threat they feel, whether this is real or perceived. When pain becomes chronic, it is no longer due to tissue damage or trauma. It is caused by a sensitive nervous system, and is affected by how the brain processes heightened nerve responses in the context of the environment. ‘Explaining pain’ is now the cornerstone of modern chronic pain rehabilitation. It is well established in research that pain science education is effective in reducing pain and disability, and establishing healthy attitudes and beliefs about pain. It is also important that psychosocial factors are screened and addressed through therapies such as cognitive behavioural therapy, mindfulness-based stress reduction and general exercise.13

Conclusion

PFM dysfunction, mainly increased tension, plays a significant role in the maintenance and exacerbation of pelvic and sexual pain. Identification of a myofascial syndrome as a cause or contributing factor is a critical step in management of patients with chronic pelvic pain. Failure to recognise pelvic floor dysfunction could certainly contribute to the 24–40 per cent negative laparoscopy rate in patients with chronic pelvic pain.14 CPP is complex, as it is generally a condition with multiple causative factors, that requires a common understanding between the patient, their loved ones and health practitioners. Research shows us that understanding lessens anxiety and can reduce the distress associated with the pain. There are many ways to increase knowledge and minimise anxiety, be it directly or indirectly. Even experienced practitioners may misdiagnose patients with pelvic pain if they do not specifically examine the pelvic diaphragm. Performing a simple musculoskeletal screen along with a pelvic muscle exam takes just a few minutes and adds valuable information to the medical assessment. Attention to the pelvic floor musculature during pelvic examinations is an effective and inexpensive diagnostic strategy that can be life-changing for patients with pelvic pain, yet requires minimal time and effort. Management must be multidisciplinary and take a biopsychosocial approach with an individualised and multimodal therapy application.

This article first appeared on AGES eScope, Volume 63, February 2017. Reproduced with permission.

Further reading

Srinivasan AK, Kaye JD, Moldwin R. Myofascial dysfunction associated with chronic pelvic floor pain: management strategies, Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2007;11:359-364.

P. Latthe, M. Latthe, L. Say, M. Gulmezoglu, K.S. Khan, WHO systematic review of prevalence of chronic pelvic pain: a neglected reproductive health morbidity, BMC Public Health. 2006;6:177.

Sinaki M, Meritt J, Stilwell G. Tension myalgia of the pelvic floor. Mayo Clin Proc. 1977;52:717-22.

Prendergast SA, Weiss JM. Screening for musculoskeletal causes of pelvic pain. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2003;46(4):773-782.

Howard FM. Chronic pelvic pain. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101(3):594-611.

References

- Mathias S, Kupperman M, Liberman R, Lipschutz R, Steege J. Chronic pelvic pain; prevalence, health related quality and economic correlates. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;87:321-7.

- Jarvis S, Abbott J, Lenart M, Steensma A. Vancaille T. Pilot study of botulinium toxin type A in the treatment of chronic pelvic pain as associated with spasm of the levator ani muscles. ANZJOG. 2004;44:46-50.

- Tu FF, As-Sanie S, Steege JF. Musculoskeletal causes of chronic pelvic pain: a systematic review of diagnosis: part I. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2005;60(6):379-385.

- Jarvis S, Abbott J, Lenart M, Steensma A. Vancaille T. Pilot study of botulinium toxin type A in the treatment of chronic pelvic pain as associated with spasm of the levator ani muscles. ANZJOG. 2004;44:46-50.

- Fall M, Baranowski AP, Elneil S, et al. EAU guidelines on chronic pelvic pain. Eur Urol, 2010;57:35-48.

- Bergeron S, Binik YM, Khalife S, Pagidas K, Glazer HI, Meana M, et al. A randomised comparison of group cognitive- behavioural therapy, surface electromyographic biofeedback, and vestibulectomy in the treatment of dyspareunia resulting in vestibulitis. Pain. 2001; 91; 297-306.

- Rosenbaum, Talli. Physiotherapy treatment of sexual pain disorders. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy. 2005;31:329-340.

- Rosenbaum, Talli. Physiotherapy treatment of sexual pain disorders. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy. 2005;31:329-340.

- Moseley, G. L., & Butler, D. S. (2015). Fifteen Years of Explaining Pain: The Past, Present, and Future. Journal of Pain, 16(9), 807-813.

- Abbott J, The use of botulinum toxin in the pelvic floor for women with chronic pelvic pain – A New Answer to Old Problems? The Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynaeology. 2008.11.006

- Tu FF, Holt J, Gonzales J, Fitzgerald CM. Physical therapy evaluation of patients with chronic pelvic pain: a controlled study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198(3):272.

- Morin M, Dumoulin C, Bergeron S, et al., Randomised clinical trial of multimodal physiotherapy treatment copared to overnight lidocain ointment in women with provoked vestibulodyania; design and methods. 2016 Contemporary Clinical Trials 46 52-59

- Vandyken C, Hilton S. Physical therapy in the treatment of central pain mechanisms for female sexual pain. Sex Med Rev. 2016; 1-11.

- Butrick CW. Pathophysiology of pelvic floor hypertonic disorders. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2009;36(3):699-705.

Leave a Reply