Maternal collapse is an acute event that involves cerebrovascular and cardiorespiratory systems, presenting as reduced or absent conscious levels at any stage in pregnancy, including up to six weeks after delivery. The incidence is approximately 1:20,000–1:30,000 internationally.1 The uniqueness of this rare event is that there are (at least) two patients – the mother, and the fetus(es). A multidisciplinary approach is necessary to enhance the survival likelihood of all involved patients – including obstetrics, anaesthesia, neonatology and, sometimes, cardiothoracic surgery. The application of early basic resuscitation techniques can greatly improve outcomes, and requires knowledge of the physiological changes of pregnancy.

Cardiovascular

Maternal heart rate and stroke volume both increase, resulting in an increased cardiac output. Blood volume increases by 30–50 per cent, with a 20 per cent increase in red blood cell volume, thus resulting in physiological anaemia. Because of this increased volume, clinical signs are a late indicator of reduced circulating volume. After 20 weeks, supine hypotension also occurs due to aorto-caval compression by the gravid uterus.

Respiratory

Maternal respiratory rate and tidal volume both increase, resulting in an increased minute ventilation. This is in part compensation for the increased oxygen demands of the uterus, placenta and fetus. The gravid uterus and cephalad displacement of the diaphragm (causing a reduced functional residual capacity) also reduces oxygen reserves. Because of this, desaturation and hypoxia occur more quickly than in the non-pregnant patient.

Abdominal/pelvic

There is a marked increased risk of gastric aspiration. This is due to both a decrease in lower oesophageal sphincter tone and an increase in intra-gastric pressure.

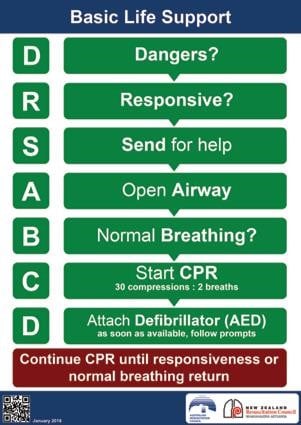

The Australian and New Zealand Committee on Resuscitation (ANZCOR) approach to basic life support follows the ‘DRABCD’ approach (Figure 1).2 It is always essential to first check for any danger to the responder before checking the pregnant woman for responsiveness, and ensuring adequate help is sought immediately. In the hospital setting this involves ensuring a Code Blue is called and mentioning it is a pregnant patient. Current guidelines are to only move the patient if they are in a hazardous position, to facilitate airway management or to control severe bleeding.

Airway

Management of the airway takes priority over other injuries, including potential spinal injury, or the health of the fetus. To clear the airway, you should open the patient’s mouth and turn their head slightly downwards. You should open the airway using a head-tilt/chin-lift manoeuvre. Place one hand on the forehead and the other to provide chin lift. In the unconscious patient, their relaxed muscles and large tongue are likely to create an obstructed airway, even if their mouth is open. It is important to identify airway obstruction early, bearing in mind that it may be partial, or that respiratory effort may be maintained in a patient with an obstructed airway. An airway obstructed with a foreign body in an unconscious patient is managed with up to five back blows followed by up to five chest thrusts.

Breathing

Assessment of breathing is performed next. You look for movement of the chest, listen for escape of air from the mouth or nose, and feel for associated movement of air. If the unconscious person is still not breathing normally despite airway opening, it is imperative to immediately begin chest compressions, followed by rescue breathing. Mouth-to-mouth or mouth-to-nose can be used; alternatively, all resuscitation trolleys should have an ambu-bag for ventilation.

Figure 1. Adult Advanced Life Support, Reproduced with permission from ANZCOR

Compressions

All patients who are unresponsive and have absent breathing require resuscitation. It is no longer recommended to feel for a pulse. Compressions should be performed at a rate of 100–120 per minute, a ratio of 30:2 breaths, and at approximately one-third of the chest depth, allowing for adequate recoil at the end of each compression.

The pregnant patient

Of note are the differences to the basic life support algorithm for the pregnant woman. While data are scarce, ANZCOR has a consensus statement that follows best available evidence. Good quality, uninterrupted chest compressions are the priority. Once adequate CPR is underway, if resources permit, the woman should have uterine displacement performed. This can be done with a towel or cushion under her right hip, or with manual displacement by another responder.

Defibrillator

Time to defibrillation is a key factor influencing survival. A defibrillator should be applied as quickly as it becomes available so that a shock can be delivered, if warranted. Defibrillators should be used on pregnant women.

This rare and challenging clinical scenario is likely to be chaotic for all involved. Clear communication, early mobilisation of help, and adherence to these protocol algorithms can help us to navigate a stressful situation, and facilitate transition to advanced life support.

References

- Lewis G. The Confidential Enquiry into Maternal and Child Health (CEMACH). Saving Mothers’ Lives: reviewing maternal deaths to make motherhood safer – 2003–2005. The Seventh Report on Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths in the United Kingdom. London: CEMACH. 2007.

- ANZCOR Guideline 2-8 – Basic Life Support 1st ed. Australian Resuscitation Council, 2016. Web. 2 Apr. 2017.

Leave a Reply