This article highlights the key principles of basic resuscitation and approaches some of the more challenging and unusual scenarios we may find ourselves in.

Initiating advanced life support

Attending a resuscitation call in the delivery unit or emergency department is undoubtedly stressful. Being the first responder to an unconscious patient outside a clinical area, without appropriate equipment or support, can unnerve even the most experienced clinician.

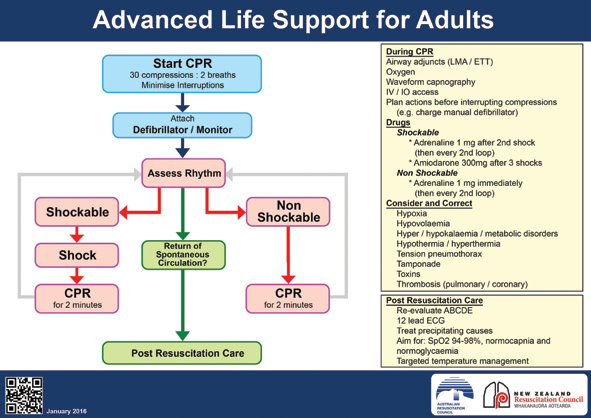

It goes without saying that help should be sought immediately. Be clear who you want (for example, obstetric emergency team), where you are (for example, level 9 obstetric clinic) and what you need (for example, perimortem caesarean section kit). Using the adult advanced life support algorithm (Figure 1) will allow you to focus on a methodical plan in assessing and managing the patient.

Intravenous access should be secured above the diaresuscitationphragm, as venous compression can hinder the delivery of intravenous drugs to the arterial vasculature. As you apply the basic principles of resuscitation, consider the aetiology of the collapse. The simple aide-memoire of 4Hs and 4Ts (outlined in Figure 1) still holds true, but other obstetric causes, including eclampsia and intracranial haemorrhage, should also be considered.1 Help should hopefully have arrived during the initial resuscitation, at which point a clear and concise handover should take place. You may decide to allow the anaesthetist to take over while you continue resuscitation or devise a surgical plan. Decisive leadership and teamwork are required at this juncture.

Figure 1. Adult Advanced Life Support, Reproduced with permission from the Australian and New Zealand Committee on Resuscitation (ANZCOR).

Perimortem caesarean section

Perhaps the toughest decision is whether to perform a perimortem caesarean section, and where to do so. Time is the most critical factor when a pregnant woman with a viable fetus arrests, and the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) recommends delivery within five minutes of cardiac arrest. Therefore, attempts to transfer the mother to the operating theatre should not occur, as this takes up valuable time. It is crucial to remember that the life of the mother comes first, and the decision to perform a perimortem caesarean section should be in the interests of maternal survival. Resuscitation efforts should continue during preparation for, and throughout delivery of the fetus. Most delivery units and emergency departments have pre-packaged perimortem caesarean section kits that contain essential equipment, including a fixed-blade scalpel, Mayo scissors, clamps and forceps. It is useful to familiarise yourself with the equipment available in your department. Transferring the patient to an appropriate location for continuing treatment and stabilisation should take place once resuscitation is successful, post-delivery.

Intraoperative cardiac arrest

The incidence of cardiac arrest during a surgical procedure is rare (seven in 10,000 surgeries).2 In this scenario, your role as a surgeon is vital, with clear communication needed across both sides of the surgical barrier. The anaesthetist is typically at the head-end, securing the airway (if not previously done) and providing haemodynamic support. Your ability to stabilise the patient by achieving haemostasis and protecting the surgical field is paramount, but you may also be asked to perform cardiopulmonary resuscitation. The drugs commonly used in a cardiac arrest include adrenaline, amiodarone and magnesium, and are usually found in the cardiac arrest trolley. Every arrest trolley and anaesthetic machine should have a folder containing emergency protocols (such as for anaphylaxis or local anaesthetic toxicity) to provide guidance in these chaotic moments. In exceptional circumstances, the surgery may be aborted to transfer the patient to a safer environment, such as the intensive care unit.

Complications from CO2 insufflation

Insufflation of carbon dioxide (CO2) during laparoscopic surgery can induce pathological cardiovascular changes, including bradycardia, arrhythmias and even cardiac arrest. This can be explained via two mechanisms: firstly, the mechanical effect of elevated intra-abdominal pressure, and secondly, the absorption of CO2 itself.

A profound vagal response to peritoneal distension is often responsible, usually preceded by severe bradycardia. Rapidly releasing the pneumoperitoneum typically reverses this, but the anaesthetist may administer an anticholinergic (atropine or glycopyrrolate) to counter the low heart rate. In susceptible patients, elevated intra-abdominal pressure can reduce venous return and in turn cardiac output, causing cardiovascular collapse. This problem can be further aggravated by the Trendelenburg position. Hypercarbia and acidosis from CO2 absorption may also trigger arrhythmias.

With a rising population of patients with poor cardiorespiratory function, raised BMI and advanced age, we may see these risk factors increase laparoscopic surgery complications. Minimising intra-abdominal pressures and insufflating the abdomen cautiously can help reduce intra-operative complication rates.

Preparation

Anaesthesia is sometimes described as the specialty of 99 per cent boredom and 1 per cent sheer panic. When a catastrophic event does occur, preparedness for the unexpected is key. Anaesthetists regularly undergo resuscitation training to prepare for that 1 per cent, as there is no substitute for practical experience.

There are various recognised multidisciplinary simulation courses tailored for obstetricians and gynaecologists, including PROMPT, ALSO and MOET. These form an integral part of training, equipping us with tools to build the confidence needed to face challenging scenarios. Hopefully, this article provides you with an understanding of how our specialties can work together to offer our patients the best care possible, in what can sometimes feel like a chaotic environment.

References

- Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecology. Maternal Collapse in Pregnancy and the Puerperium. Green-top Guideline No. 56, January 2011.

- Goswami S, Brady JE, Jordan DA, Li G. Intraoperative cardiac arrests in adults undergoing non-cardiac surgery: incidence, risk factors, and survival outcome. Anesthesiology. 2012;117(5):1018-1026.

Leave a Reply