Menopause is the final menstrual period. The menopausal transition is the time from the onset of menstrual cycle changes or vasomotor symptoms until one year after the final menstrual period.1 The National Institute of Health (NIH) associates four cardinal symptoms with the menopausal transition: vasomotor symptoms (VMS) of hot flushes and night sweats, poor sleep, adverse mood and vaginal dryness/dyspareunia, now known as the genito-urinary syndrome.2 The menopause transition starts at around 47 years and lasts for five to eight years on average. The nature and severity of symptoms may vary between women from different ethnicities and geographical locations.3 In women over 45 years of age, irregular or absent menstruation, especially in the presence of VMS, is diagnostic of the menopause and usually no investigations are required.4 5 Women commonly have more than one symptom at menopause, and how bothersome symptoms are will guide treatment.

Hormone therapy (HT) is the most effective treatment for VMS, with reductions in both frequency and severity of around 75 per cent. HT is not indicated for the prevention of chronic disease. Dosing of HT should start low, for example 0.3mg of conjugated equine oestrogens, ≤1mg 17β oestradiol or oestradiol valerate, 25µg transdermal patch and may take up to six to eight weeks before there is adequate symptom relief.6 It is the inclusion of progestogen that appears to increase breast cancer risk, but this is required to prevent endometrial hyperplasia and cancer risk in women with a uterus. With low-dose oestrogen use, 5mg of medroxyprogesterone acetate for 14 days (sequential therapy) and 2.5mg daily (combined continuous therapy) will give endometrial protection.7 Observational data show that transdermal delivery minimises the risk of stroke and VTE and also that the type of progestin may alter breast cancer risk. Micronised progesterone has less risk than testosterone-derived products.8

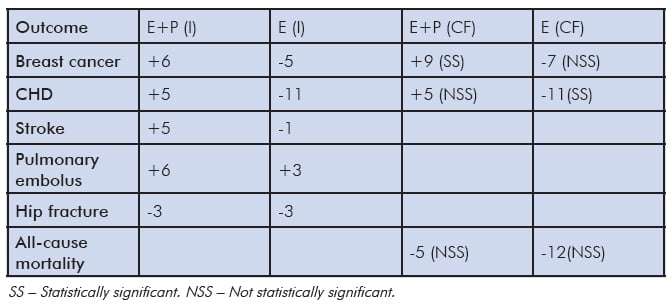

Table 1. Absolute risks attributable to HT per 10000 women/year aged 50–59 years during study intervention period (I) and 13 years of cumulative follow up (CF).7

HT should not be used in women with unexplained vaginal bleeding, active liver disease, previous breast cancer, coronary heart disease, stroke, personal history of thromboembolic disease or known high inherited risk. These women can be offered non-hormonal alternatives. A systematic review has identifed that clonidine, selected selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI) and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SRNI) and the gaba-agonist gabapentin are superior to placebo for VMS, reducing these symptoms by around 50–60 per cent compared to 75 per cent with oestrogen.9

Heavy periods in women over the age of 40 years should be investigated before starting HT. As HT is not a treatment for heavy menstrual bleeding, a low-dose combined oral contraceptive pill or intrauterine progestogen may be preferable. In postmenopausal women, unscheduled bleeding in the first six months of combined continuous HT use is common and does not necessarily need to be investigated, provided that cervical smears are up to date. Unscheduled bleeding after six months or new onset unscheduled bleeding should be investigated.10

Perimenopausal women using sequential HT who are sexually active will also require contraception. Contraception should be used for two years after the last menstrual period in women aged under 50 and one year in those over 50.11 The method used should consider the woman’s medical eligibility criteria. All oestrogen-based contraceptives (pills, patches, vaginal rings) can be used in non-smoking women without cardiovascular or thrombotic risk factors until the age of 50 years and, along with providing contraception, will relieve VMS. Barrier methods (condoms, caps), spermicides and copper-bearing intrauterine devices can be used by women on HT. Intrauterine levonorgestrel (LNG-IUS) provides effective contraception and has the benefits of endometrial protection in addition to treating heavy menstrual bleeding.12

Absolute risks are small in healthy women during the menopause transition or within ten years of menopause (Table 1). The increased risk of stroke and pulmonary embolus and the decreased risk of hip fracture disappear within 2.4 years of stopping HT. We now have 13 years of cumulative follow up, in other words, time in the WHI study using HT and follow up after study discontinued. The findings for women aged 50–59 years were that the risk of breast cancer remained for those women who had taken combined HT. For those who had taken oestrogen-only therapy, there was a decreased risk of coronary heart disease (CHD). There was no statistically significant difference in all-cause mortality for either group of women.

The duration of treatment for VMS may need to be longer than previously believed. About 20 per cent of women in their late 50s, 10 per cent of women in their 60s and five per cent of women in their 70s experience persistent symptoms.13 For older women, transdermal delivery of oestrogen along with micronised progesterone, if they have a uterus, is likely to confer least risk. HT can be stopped every few years to see if symptoms have disappeared. Vaginal symptoms can also appear relatively early in the menopausal transition and, unlike VMS that tend to improve over time, do not get better without ongoing treatment. Vaginal oestrogen will improve both vaginal symptoms along with other aspects of the genitourinary syndrome (vaginal irritation, urgency, urge incontinence and dysuria) and is likely to require at least six to eight weeks of use before benefit is seen. Oral oestrogen may improve vaginal symptoms, but makes incontinence worse.14 Low-dose, local vaginal oestrogen should be continued as long as symptoms persist. There are no safety data extending beyond 12 months, but no time limits for therapy use have been established.15

The menopause transition usually does not require treatment. For those women with troublesome symptoms affecting quality of life, several options are available. Clinicians and women need to know about which symptoms are due to menopause, the available treatment options and their risks and benefits to enable shared decision-making. This is appropriate in general practice, but may require further referral when there are medical conditions or no improvement of symptoms. Treatment should be reviewed within three months for efficacy, then at least annually. Treatment can initially be stopped after a few years to see if symptoms have disappeared.

References

- STRAW 10 Collaborative Group SD. Harlow M, Gass JE, Hall R, et al. Executive summary of the Stages of Reproductive Aging Workshop + 10: addressing the unfinished agenda of staging reproductive aging. Menopause. 2012;19:387-395.

- Santoro N. Perimenopause: from research to Practice. Journal of Women’s Health. 2016;25:332-339.

- Roberts H, Hickey M. Managing the menopause :an update. Maturitas. 2016;86:53-8

- Neves-e-Castro M, Birkhauser M,Samsioe G Lambrinoudaki I et al. EMAS position statement: the ten point guide to the integral management of menopausal health. Maturitas. 2015;81:88-92.

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. NICE Clinical Guideline Menopause (2015) www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng23/resources/menopause-diagnosis-and-management-1837330217413.

- Roberts H, Hickey M. Managing the menopause: an update. Maturitas. 2016;86:53-8.

- Roberts H, Hickey M, Lethaby A. Hormone therapy in postmenopausal women and risk of endometrial hyperplasia: A Cochrane review summary. Maturitas. 2014;77:4-6.

- Roberts H, Hickey M. Managing the menopause: an update. Maturitas. 2016;86:53-8.

- Roberts H, Hickey M. Managing the menopause :an update. Maturitas. 2016;86:53-8.

- Roberts H, Hickey M. Managing the menopause: an update. Maturitas. 2016;86:53-8.

- Neves-e-Castro M, Birkhauser M,Samsioe G Lambrinoudaki I et al. EMAS position statement: the ten point guide to the integral management of menopausal health. Maturitas. 2015;81:88-92.

- Roberts H, Hickey M. Managing the menopause :an update. Maturitas. 2016;86:53-8.

- Santoro N. Perimenopause: from research to Practice. Journal of Women’s Health. 2016;25:332-339.

- Nelson HD, Walker M, Zakher B, Mitchell J. Menopausal hormone therapy for the primary prevention of chronic conditions: a systematic review to update the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendations. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(2):104-113.

- The North American Menopause Society (NAMS) Position statement: The role of local vaginal estrogen for treatment of vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2007;14:357-369.

Leave a Reply