The decision to perform an emergency peripartum caesarean hysterectomy is a critical one for any obstetrician. With the rising caesarean section rate, this is a situation we will face more often in the future. The first successful caesarean hysterectomy was described in 1876, by Dr Eduardo Porro of Milan, Italy.

Incidence and cause

Emergency peripartum hysterectomy (EPH) is defined as a hysterectomy performed immediately following, or within 24 hours of, delivery. The reported incidence in developed countries ranges from 0.2 to five per 1000 deliveries.1 2

The Royal Hospital for Women, Sydney, reported an incidence of 0.85 per 1000 births. More recently, the Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital reported 15 years of data with an incidence of 0.6 per 1000 births.3 The National Women’s Hospital, Auckland, reported a similar incidence of 0.87 per 1000 births in 2015.4 In a New Zealand study in 2011, 95 per cent of EPHs were following caesarean delivery.5

The most common causative factors are:

- Abnormal placentation (morbidly adherent placenta 55%, and placenta praevia 20%)

- Uterine atony6

- Uterine scar rupture.

Risk factors

Over the past 20 years, the risk-factor profile for EPH has changed. There has been a shift in risk-factor profile, with atony and uterine rupture no longer the most common causes, those now being superseded by abnormal placentation, which is mainly related to prior caesarean section.7 8

In a 10-year data series of EPH from Sydney’s Royal Hospital for Women in 2011, 31 cases were reported; 54.8 per cent were due to abnormal placentation, 12.9 per cent due to uterine atony and 6.5 per cent due to uterine rupture.9

Placenta praevia is associated with an approximately five per cent risk of hysterectomy, usually in association with placenta accreta. Frequency of abnormal placentation increases with number of previous caesarian births and advanced maternal age. Caesarean delivery and previous uterine surgery appear to be key risk factors for EPH. Knight et al quotes risk of EPH lowest in women undergoing a first delivery that was vaginal (1:30 000); and highest in women with two or more prior caesarean births (1:220).10 Silver et al quotes a risk of EPH of one per cent following first, second or third caesareans; two to four per cent following fourth or fifth procedures; and nine per cent for six or more caesareans.11

Other risk factors include advanced maternal age, multiparity, multiple gestation, gestational diabetes, infection, and previous uterine surgery.12 13 More recent papers have also found a link between assisted reproductive treatment as a risk factor independent of the mode of delivery.14

Indications and prevention measures

The main indication for EPH is massive obstetric haemorrhage that is unresponsive to conservative measures. Postpartum haemorrhage (PPH) is defined as blood loss greater than 500 mL at vaginal delivery and 1000 mL at caesarean.15 Rapid management of PPH is an essential skill that all obstetric teams require to reduce risk of an EPH.

It is important that placental location is carefully evaluated antenatally in women with a history of prior caesarean birth. Those with a suspected adherent placenta on ultrasound scan should be referred for further imaging, such as MRI.

Referral to a tertiary centre is recommended. These cases require a multidisciplinary review and planned prelabour delivery with obstetric, anaesthesia, interventional radiology, urology, and vascular/gynaeoncological surgical team involvement.

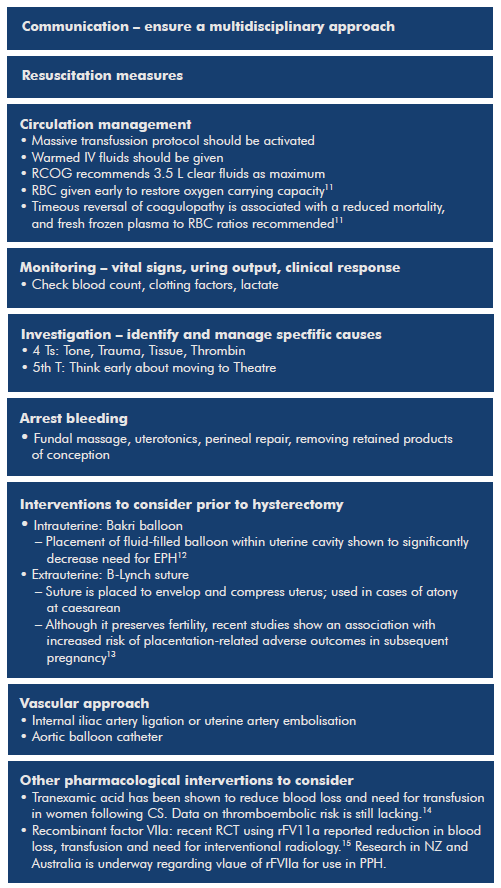

Basic PPH management is outlined in Figure 1.

If hysterectomy appears inevitable, prompt procedure results in lower transfusion rates and less overall morbidity.16

Procedure should be undertaken without delay for cases of:17

- Bleeding refractory to conservative measures

- Suspected accreta

- Uterine rupture.

Direct aortic compression can be used as a temporary measure to allow time for resuscitation to catch up and appropriate senior surgical support to be available.

The decision to perform an EPH should be made by a senior clinician and preferably after discussion with a second senior consultant.18

Procedure19

- Skin incision – both midline and low transverse can be used. Midline incision preferred

- Avoid the placenta; if there is a known praevia and accreta, consider a classical uterotomy incision

- Close uterotomy incision following delivery. Adherent placentas should be left in situ

- Careful bladder dissection off anterior lower uterine segment

- Sharp dissection should be performed to minimize bladder injury and bleeding. Aim 1–2 cm below the cervico-vaginal junction

- Understand ureteric anatomy

- Round ligament identification, double clamped laterally

- Utero-ovarian ligament. Special care is needed as vessels are often dilated and tissues can tear easily. Ovaries almost always preserved

- Identify the uterine vessels. Three clamps can be used for extra security, two on the active vessel side and one on the uterine side

- Supra-cervical (subtotal) hysterectomy can be performed at this stage.

- Cardinal ligaments. Clamp, cut and ligate in 1–1.5 cm tissue sections until the external os is reached. Continuous careful inspection of bladder and ureters

- Clamp across vaginal angle and uterosacral ligament, enter vaginal mucosae anteriorly, just below cervix and remove uterus. Secure vaginal vault angles and cardinal ligaments

- There are no specific guidelines for closure of vaginal vault. Continuous or interrupted sutures

- Consider perioperative thromboprophylaxis and antibiotic cover

- Haemostatic agents should be considered if required. Agents such as FloSeal, Fibrillar, Surgicel may be effective; however, none replace meticulous surgical technique

- Subtotal hysterectomy is thought to be faster, associated with less blood loss, less bladder/ureteric injury and is often the procedure of choice in haemodynamically unstable patients16

- Total hysterectomy should be considered to reduce problems associated with the residual cervical stump, especially if there is cervical bleeding or an accreta extending to the cervix

- A retrospective cohort study of 163 EPHs found no difference in total operating time, estimated blood loss,units of blood transfused, preoperative on and postoperative haemoglobin

Figure 1. Basic PPH management includes (simultaneously).20

Undertaking an EPH is more complicated than a standard hysterectomy for the following reasons:

- Distended soft cervix – difficult to identify the internal os

- Engorged and dilated pelvic blood vessels – increase risk of bleeding

- Friable and oedematous tissue – increase bleeding

- Large bulky uterus – obscure operating field

- Potentially unstable patient.

Consequences and outcomes

EPH has multiple consequences, affecting women physically and emotionally, as well as affecting the economy. The mortality and morbidity associated with EPH can be due to either the surgical procedure itself, or from the effect of the primary massive obstetric haemorrhage.

Worldwide mortality rates have been reported ranging from two to 15 per cent, with higher rates in developing countries.21 22 23 24

Morbidity is associated with prolonged hospital stay, ICU/HDU admission, increased surgical complications such as ureteric injury (6% to 15%), coagulopathy, massive transfusion, sub-fertility, emotional response and need for psychological support.25

Latest research

Research is scarce regarding EPH as is it a rare event. Most literature surrounding the topic are case studies or 10–20 year reports on incidence, epidemiology and management. Interestingly, in 2014, De Miguel et al published a report of 23 EPHs analysing the pathology of the placental site. They found that one-third of EPHs performed during a 10-year period were associated with placental site anomalies originating in the implantation site intermediate trophoblast.26

Conclusion

Massive obstetric haemorrhage requiring emergency peripartum hysterectomy is an uncommon, but serious, complication of childbirth, carrying significant morbidity and mortality. Prevention, rapid identification and active management of bleeding at, or following, delivery is essential to reduce the need to perform this procedure. With abnormal placentation increasingly becoming the major risk factor for emergency peripartum hysterectomy, it is important to address the increasing caesarean section rate.

Tips for a safe emergency peripartum hysterectomy

- Communication and multidisciplinary teamwork is key

- Departmental simulated drills for PPH management

- Massive transfusion protocol

- If placenta is adherent, do not try to remove

- Understand anatomy of ureters, bladder and pelvic vessels

References

- Cheng HC, Pelecanos A, Sekar R. Review of peripartum hysterectomy rates at a tertiary Australian hospital. ANZJOG. 2016;56(5) doi:10.1111/ajo.12519.

- Knight M, Kurinczuk JJ, Spark P, Brocklehurst P. United Kingdom Obstetric Surveillance System Steering Committee. Cesarean delivery and peripartum hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111(1):97-105.

- Cheng HC, Pelecanos A, Sekar R. Review of peripartum hysterectomy rates at a tertiary Australian hospital. ANZJOG. 2016;56(5) doi:10.1111/ajo.12519.

- National Woman’s Health, Annual Clinical report, 2015. P.157. Available from: http://nationalwomenshealth.adhb.govt.nz/ Portals/0/Annual_Clinical_Report_%20 2015%20ONLINE.pdf.

- Wong TY. Emergency peripartum hysterectomy: a 10-year review in a tertiary obstetric hospital. New Zealand Medical Journal. 2011;124(1345):34-9.

- Awan N, Bennett MJ, Walters WA, Emergency peripartum hysterectomy: A 10-year review at the Royal Hospital for Women, Sydney. ANZJOG. 2011;51(3):210–215. doi:10.1111/ j.1479-828X.2010.01278.x.

- Cheng HC, Pelecanos A, Sekar R. Review of peripartum hysterectomy rates at a tertiary Australian hospital. ANZJOG. 2016;56(5) doi:10.1111/ajo.12519.

- Awan N, Bennett MJ, Walters WA, Emergency peripartum hysterectomy: A 10-year review at the Royal Hospital for Women, Sydney. ANZJOG. 2011;51(3):210–215. doi:10.1111/ j.1479-828X.2010.01278.x.

- Wong TY. Emergency peripartum hysterectomy: a 10-year review in a tertiary obstetric hospital. New Zealand Medical Journal. 2011;124(1345):34-9.

- Knight M, Kurinczuk JJ, Spark P, Brocklehurst P. United Kingdom Obstetric Surveillance System Steering Committee. Cesarean delivery and peripartum hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111(1):97-105.

- Silver RM, Landon MB, Rouse DJ, et al. Maternal morbidity associated with multiple repeat cesarean deliveries. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107:1226.

- Awan N, Bennett MJ, Walters WA, Emergency peripartum hysterectomy: A 10-year review at the Royal Hospital for Women, Sydney. ANZJOG. 2011;51(3):210–215. doi:10.1111/ j.1479-828X.2010.01278.x

- Hernandez JS, Nuangchamnong N, Ziadie M, et al. Placental and uterine pathology in women undergoing peripartum hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119:1137.

- Cromi A, Candeloro I, Marconi N, et al. Risk of peripartum hysterectomy in births after assisted reproductive technology.Fertility and Sterility. 2016;106(3):623-628.

- WHO recommendations for the prevention and treatment of postpartum haemorrhage. 2012. WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data. Available from: http:// apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665_eng.pdf

- Knight M, Kurinczuk JJ, Spark P, Brocklehurst P. United Kingdom Obstetric Surveillance System Steering Committee. Cesarean delivery and peripartum hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111(1):97-105.

- RCOG. Prevention and Management of Postpartum Haemorrhage. GTG 52, 2009, revised 2011. Available from: www.rcog. org.uk/globalassets/documents/guidelines/gt52postpartumhaemorrhage0411.pdf.

- Hernandez JS, Nuangchamnong N, Ziadie M, et al. Placental and uterine pathology in women undergoing peripartum hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119:1137.

- Matthews G, Rebarber A. Grand rounds: practical perspective on cesarean hysterectomy: when, why, and how. Contemporary OB/GYN. 2010;55:30-40.

- RCOG. Prevention and Management of Postpartum Haemorrhage. GTG 52, 2009, revised 2011. Available from: www.rcog. org.uk/globalassets/documents/guidelines/ gt52postpartumhaemorrhage0411.pdf.

- Cheng HC, Pelecanos A, Sekar R. Review of peripartum hysterectomy rates at a tertiary Australian hospital. ANZJOG. 2016;56(5) doi:10.1111/ajo.12519.

- National Woman’s Health, Annual Clinical report, 2015. P.157. Available from: http:// nationalwomenshealth.adhb.govt.nz/ Portals/0/Annual_Clinical_Report_%20 2015%20ONLINE.pdf.

- Wong TY. Emergency peripartum hysterectomy: a 10-year review in a tertiary obstetric hospital. New Zealand Medical Journal. 2011;124(1345):34-9.

- Awan N, Bennett MJ, Walters WA, Emergency peripartum hysterectomy: A 10-year review at the Royal Hospital for Women, Sydney. ANZJOG. 2011;51(3):210–215. doi:10.1111/ j.1479-828X.2010.01278.x.

- Imudia AN, Hobson DT, Awonuga AO, et al. Determinants and complications of emergent cesarean hysterectomy: supracervical vs total hysterectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203:221.e1.

- De Miguel JR, Quintana R, González-Rodilla I, et al. Exaggerated placental site/placental site trophoblastic tumor: an underestimated risk factor for emergency peripartum hysterectomy. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 2014;41(6):638-40.

Leave a Reply