It is a common scenario for doctors in training. You see a patient with your consultant and there is an abnormal rash, ECG or snapshot of a CT scan that needs further exploration. You’ve suddenly got two choices in front of you. You can attempt to describe the anomaly to the specialist on the other line and try your absolute hardest to ignite your inner Shakespeare. Or, you can pull your ectopic brain out of your pocket, take a photo and send your digital Van Gogh directly to the specialist. I don’t know about you, but my Latin just isn’t that good. It is no surprise then that clinical images are being taken on smartphones and sent to colleagues for further opinion every day, but what exactly are the broader implications of our current de facto practices? To understand how we’ve ended up where we are today, we need to look at information in healthcare at a broader level, specifically outlining issues of privacy, confidentiality and consent.

Privacy is quite a broad concept and there is no all-encompassing, singular definition of what privacy means. Roger Clarke defines privacy at the broadest level as, ‘the interest that individuals have in sustaining a personal space, free from interference by other people and organisations’.1 Privacy is not a static concept and has multiple subjective boundaries.2 The degree to which these align enables a clearer definition of privacy for a given situation and problems arise when the expectations of privacy conflict with one another. For example, the Victorian government recently introduced laws to make vaccination compulsory for children to attend childcare or kindergarten.3 With Victorian vaccination rates at 92 per cent, it is clear that the majority of Victorians are willing to forego some personal privacy of the body to protect their public health. However, a small minority continue to challenge the idea of vaccination. These conflicts in expectation of privacy are ultimately managed by the Australian legal system.

Privacy is also intertwined with the concepts of confidentiality and consent. If information is considered private, then there are expectations around how that data will be managed, including an expectation of security. Confidentiality is the idea that information communicated between parties will be kept in confidence.4 Confidentiality is also relative, and broader interests may override the expected confidence. For example, medical practitioners are sometimes directed to break confidentiality if there is an overriding public interest, such as can be the case with specific dangerous infectious diseases.5

The provision of informed consent is discussed in privacy legislation. Informed consent is a voluntary choice or permission, made freely by an individual who has sufficient information available to understand the implications of their decision.6 In obtaining this consent, an individual must be informed of how their data are to be used and shared, including instances in which these restrictions may be overridden through exemptions. Models for the sharing of healthcare information operate either by opt-in or opt-out mechanisms for consent, whereby patients must either provide informed consent to enter the system, or elect to exit the system after having already been added to it.

So what does all of this mean for the doctor in training and our troublesome rash? We all carry devices on our person with the ability to record high-definition photos, video and audio and yet we have no uniform, secure systems with which to transfer them to each other. When you use bedside media to deliver medical care, you’re creating a new part of the medical record and there are rules and expectations around the management of this record, as we have touched upon. Let’s say that you decide that media is necessary to deliver medical care to your patient. Does the patient understand what will be done and why it needs to be done? Has their consent been obtained and recorded properly? How will the images be stored? Do you have automatic backup services on your phone that might send that data to the other side of the world, outside of an Australian legal jurisdiction? What policies do your local hospitals or clinics have in place for these situations? How will you store the media in the record for the required amount of time? What will you do if the patient revokes consent? Suddenly, our rash doesn’t seem like just a small problem anymore.

The reality is that storing electronic media in modern-day clinical records is a veritable nightmare of legislation, policy and procedure. It’s so complicated and so variable that it is often easier to take the picture, send it off and just pretend it never existed. However, it did exist and will continue to exist in devices and storage outside of your control. The reality is far from ideal. Doctors can’t wait for the system to evolve and catch up. They need to deliver the best care they can for their patients right now, and often that brings tenants of practice into conflict with each other.

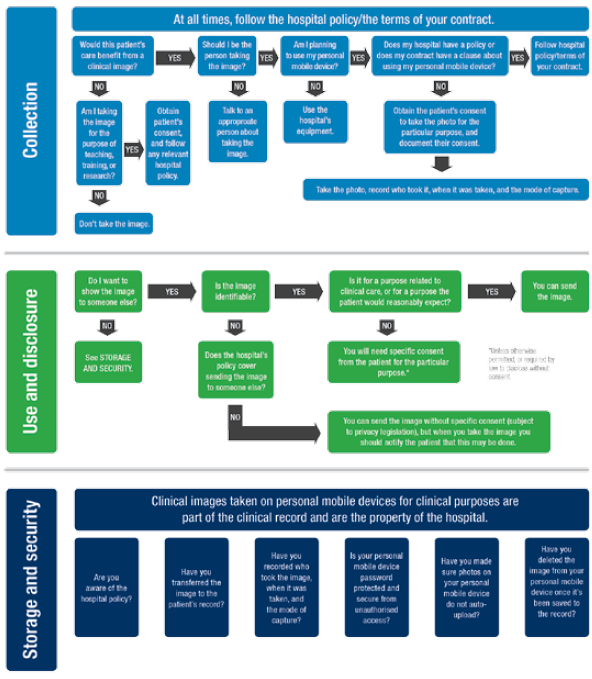

In 2014, the Australian Medical Association (AMA) joined forces with the Medical Indemnity Industry Association of Australia (MIIAA) to develop a clear guideline for clinical images and the use of personal mobile devices.7 This guideline provides clear information on the responsibilities of doctors and medical students in dealing with clinical images. The guideline includes a single-page flowchart to inform decisions made at the bedside with regard to collection, use, disclosure, storage and security (see Figure 1). This body of work recognises the enormous complexity of clinical imagery and the benefits it can provide, and helps us to navigate these complicated waters.

The sad reality of modern medicine and modern technology is that the disparity between the two is a gulf that seemingly continues to expand. I can get off of a plane anywhere in Australia and my phone can instantly find the closest cinema, find the most popular movie and buy me two tickets automatically charged to my credit card in mere seconds. However, if I’ve got an unconscious patient and I want to send the images of their expanding subdural haemorrhage to the nearest neurosurgeon for rapid management stratification, then I must think twice.

I recognise that we have exemplary clinical photography departments in our hospitals. I understand that there are singular examples of where clinical messaging is done well in parts of Australia. But in a day and age where I can instantly video conference with my nearest and dearest, it seems unreasonable to don my stethoscope and be forced to deprive my patients of these same technological benefits. We are in an age of clinical medicine where the use of smartphones at the point of care is not fringe practice or cutting-edge medicine. It’s here and now, and we ignore the implications of this fact at our own peril.

Figure 1. AMA decision-making process flowchart. Reproduced with permission from AMA

References

- Clarke R. Roger Clarke’s ‘Privacy Introduction and Definitions’ [Internet]. 1997 [cited 2015 Aug 18]. Available from: www. rogerclarke.com/DV/Intro.html.

- Foord K. Defining Privacy: Occasional Paper | Victorian Law Reform Commission [Internet]. Victorian Law Reform Commission; 2002 [cited 2015 Aug 22]. Available from: www. lawreform.vic.gov.au/projects/workplace-privacy/defining-privacy-occasional-paper.

- ABC. New ‘no jab, no play’ vaccination laws to be introduced in Victoria – ABC News (Australian Broadcasting Corporation) [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2015 Aug 22]. Available from: www.abc.net. au/news/2015-08-16/no-jab-no-play-laws-to-be-introduced-in-victoria/6700644.

- TCLS. What is confidentiality? – Townsville Community Legal Service [Internet]. 2013 [cited 2015 Aug 22]. Available from: www.tcls.org.au/01_cms/details. asp?ID=71.

- Department of Health WA. Patient Confidentiality [Internet]. 2013 [cited 2015 Aug 20]. Available from: www.health.wa.gov.au/circularsnew/circular.cfm?Circ_ ID=13003.

- NHMRC. Chapter 2.2 General requirements for consent. National Health and Medical Research Council [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2015 Aug 22]. Available from: www.nhmrc.gov. au/book/chapter-2-2-general-requirements-consent.

- AMA. Clinical images and the use of personal mobile devices [Internet]. Australian Medical Association. 2014 [cited 2016 Jul 15]. Available from: https://ama. com.au/article/clinical-images-and-use-personal-mobile-devices.

Leave a Reply