Obstetricians and gynaecologists have chosen a career that is both clinically rewarding and also inherently risky, medicolegally. While it is important to maintain clinical and surgical skills to the standards expected of RANZCOG, the Medical Council of New Zealand and the Medical Board of Australia, older studies of obstetricians and gynaecologists1 and more recent ones of physicians2 show that focusing only on ‘technical’ competence does not protect clinicians from complaints and claims.

The literature consistently shows that one of the main drivers for complaints and litigation is poor communication3 4 and that patients often use clinicians’ communication skills as a proxy marker for their technical competence.5

From the Medical Protection Society’s (MPS) experience, one important way to effectively reduce medicolegal risk is by improving our skills as communicators. This includes:

- communicating effectively with a broad audience (patients, their families and our colleagues);

- communicating well using different means (verbally, non-verbally and in writing);

- communicating different content(breaking bad news, communicating risk and shared decision-making are areas that have been particularly well researched);

- establishing and managing expectations, both realistic and unrealistic; and

- establishing ways to check whether our communication has been understood.

A review of communication skills cites several barriers to good communication.6 These include workload, deterioration in communication skills over time and reluctance of either the doctor or the patient to share information and decisions. While acknowledging the challenges that exist, this article aims to highlight strategies to help overcome these barriers that are both time-efficient and effective in reducing patient dissatisfaction.

Communication with patients

The communication behaviour of doctors within consultations has been well-studied and observed. A study by Rodriguez et al, for example, showed significantly fewer complaints for doctors who explained things clearly, gave enough information, were perceived as caring and kind, knew the medical history and spent enough time with the patient.7 Several skills can be used to ensure you make a good impression with your patients, rather than a potentially misconceived view of a rushed, busy clinician with other things to do. The opening phase of the consultation, sometimes termed the ‘golden minute’, is the best opportunity to create this good impression. The skills discussed, therefore, focus largely on the start of the consultation, but obviously can be applied at other stages. Most patients note the non-verbal skills of the doctor more than they report on other aspects.8 9 For example, you seldom hear a patient saying, ‘that doctor’s examination skills were second to none.’ You are far more likely to hear patients reporting, ‘she was very kind’ or ‘he explained everything clearly to me’.

Greeting the patient with a smile and introducing yourself is an important start. Try to ensure eye levels are the same. The power differential between doctor and patient is never more marked than when the patient is lying down and the doctor remains standing. Interestingly, the simple task of seating yourself also creates an impression that you are spending more time with the patient.10

Part of the ‘golden minute’ skills involve patient-centred consulting through active listening and empathy. Patients have usually rehearsed a story before the consultation and there is good evidence that doctors often do not listen to this story and interrupt within the first 20 seconds.11 This interrupting is often thought by the doctor to be time-efficient. By the patient, however, it may be perceived as rude or uncaring and creates a negative perception of the doctor. If uninterrupted, most patients will tell their story within 90 seconds and then feel that the doctor has listened to them.12 Patients often provide important information in those 90 seconds, meaning that additional questions from the doctor become redundant. So, counterintuitively, it is often more time-efficient to listen without interrupting for the first 90 seconds, rather than rush into closed clinical questions.

Empathic skills involve noting cues and overtly responding to them with short ‘touch and go’ empathic statements such as ‘that sounds difficult’ or ‘you must have been very frightened’. Empathic responses provide the patient with a receipt that you have heard and understood them, and enhance the impression of a clinician who is caring and kind. These statements are time-efficient and result in shorter consultations.13 Following this with establishing the concerns and expectations of the patient will help to demonstrate a patient-centred approach.

Communicating with patients and their families

Sometimes it is not the patient who instigates the complaint, but a family member. Therefore, where possible and where the patient gives consent, it is wise to involve significant family members in discussions around patient care where appropriate. The same principles of listening and empathising with family members can be used.

Discussions with patients and their relatives become particularly important when things have gone wrong. The use of effective communication skills as part of open disclosure can help reduce your medicolegal risk.14

Checking for understanding

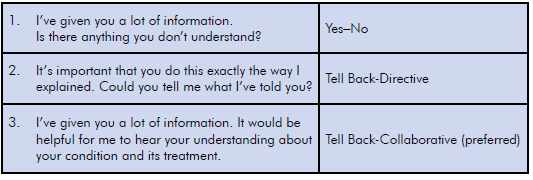

No matter how good our communication with the patient may be, there is only one way to assess whether the intended audience has understood: ask. Three methods to check understanding are shown below (see Table 1). Kemp studied the ways that doctors check for understanding and clearly demonstrated that one method is most likely to lower medicolegal risk and is preferred by patients.15

Table 1. Three methods to check patient understanding.

Most doctors will check for understanding using the first two methods. However, the third method creates a ‘shame-free’ zone where, if patients do get something wrong, it implies the clinician is at fault for not having made things clear. This allows the clinician to correct the error without the patient feeling inferior. Interestingly, as well as offering the lowest medicolegal risk, Kemp’s paper showed patients have a strong preference for the Tell Back-Collaborative approach.

Communicating with colleagues

The term ‘medical jousting’ has been coined to describe the staggering statistic drawn from a study in obstetrics and gynaecology suggesting that as much as 60 per cent of litigation is instigated at the suggestion of another healthcare professional.16 Consideration therefore needs to be given to how we communicate with our colleagues as well as how we respond to comments made about our colleagues. The basic principles are that a good working relationship with colleagues is likely to lead to support for the patient and yourself, should an adverse outcome occur. The use of standardised and reliable techniques for clinical communication with colleagues has been well tried-and-tested in a variety of settings and is also well-described. Additionally, just as it is important for you to check the patient’s understanding, there is evidence to suggest that asking colleagues to repeat back vital information can reduce errors.17

Effective communication in summary

While there are some aspects of risk that are inherent to the clinical nature of the specialty of obstetrics and gynaecology, there are some risks that are modifiable, which largely relate to communication. By maximising verbal and non-verbal skills, doctors can exert some control over the impressions patients create of them. A doctor who is perceived by their patients as someone who listens, appears caring and kind and is focused on their needs, can go a significant way to reducing the clinician’s individual medicolegal risk.

MPS, and its commercial arm, Cognitive Institute, offer a variety of workshops for clinicians wishing to further enhance their confidence and competence in communicating with patients and colleagues. As recognised leaders in communication skills training for healthcare professionals, MPS and Cognitive Institute offer short, practical skills courses for busy clinicians as well as more in-depth programs.

More information is available at

www.medicalprotection.org/newzealand and www.cognitiveinstititue.org.

References

- Entman SS, Glass CA, Hickson GB, et al. The relationship between malpractice claims history and subsequent obstetric care. JAMA. 1994 Nov 23;272(20):1588-91.

- Reid R et al. Associations Between Physician Characteristics and Quality of Care, Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(16):1442-1449.

- Beckman HB, Markakis KM, Suchman AL & Frankel RM. The doctor-patient relationship and malpractice: Lessons from plaintiff depositions. Arch Int Med. 1994; 154:1365-1370.

- Stephen F et al. A Study of Medical Negligence Claiming in Scotland, Scottish Government. 2012.

- Mangels LS. Tips from Doctors who’ve never been sued. Med Econ. 1991;8(4):56-8,60-64.

- Ha JF, Longnecker N. Doctor-patient communication: a review. The Ochsner Journal. 2010 Mar;10(1):38-43.

- Rodriguez H et al. Relation of patients’ experiences with individual physicians to malpractice risk. Int J Qual Health Care. 2008;20(1):5-12.

- Silverman J, Kinnersley P. Doctors’ non-verbal behaviour in consultations: look at the patient before you look at the computer. Br J Gen Pract. 2010;60(571):76.

- Marcinowicz L et al. Patients’ perceptions of GP non-verbal communication: a qualitative study. Br J Gen Pract. 2010;60(571):83-87.

- Swayden KJ et al. Effect of sitting vs. standing on perception of provider time at bedside: a pilot study. Patient Education and Counselling. 2012;86(2):166-171.

- Rhodes K et al. Resuscitating the physician-patient relationship: emergency department communication in an academic medical centre. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;44(3):262-267.

- Langewitz W et al. Spontaneous talking time at start of consultation in outpatient clinic: cohort study. BMJ. 2002;325(7366):682-3.

- Levinson W et al. A study of patient clues and physician responses in primary care and surgical settings. JAMA. 2000;284(8):1021-1027.

- Schostok KV. The development of full-disclosure programs: case studies of programs that have demonstrated value, in principles of risk management and patient safety. 2010. Jones & Bartlett Learning.

- Kemp EC et al. Patients prefer the method of ‘tell back-collaborative inquiry’ to assess understanding of medical information. JABFM. 2008;21(1):24-30.

- Hickson GB and Entman SS, Physician practice behavior and litigation risk: evidence and opportunity. Clin Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2008;51(4):688-699.

- Boyd M, et al. Read-back improves information transfer in simulated clinical crises. BMJ. 2014;23:989-993. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2014-003096.

Leave a Reply