In 2009, media reports emerged regarding Nadya Suleman, a woman in the US who had become pregnant following the transfer of 12 embryos and had eight fetuses who were subsequently delivered. This highlighted the dangerous practices in the US IVF industry, where multiple embryos were transferred. This still continues today as evidenced by the SART Database, which publishes the activity and success rates of every registered USA clinic. Worldwide, transfer of multiple embryos following IVF is the norm as clinics seek a competitive advantage in providing high pregnancy rates. Even in the UK, elective single embryo transfer is rare. There is no country in continental Asia, Africa or South America that replaces only one embryo electively and multiple pregnancy rates are routinely above 20 per cent, with the attendant complications known to all obstetricians.

The maternal and fetal complications of a multiple pregnancy following IVF have been well documented (but appear to be no worse than those of spontaneously conceived multiples, providing they are not monozygous). However, unlike naturally occurring multiples, the occurrence of multiple pregnancies in IVF is largely preventable. Even the occurrence of a single baby after transferring multiple embryos is not the best outcome: the perinatal mortality of a singleton conceived after double embryo transfer is higher than a singleton conceived after single embryo transfer.1

In Australia and New Zealand and parts of Europe, including Scandinavia, Belgium and the Netherlands, single embryo transfer has been advocated for more than a decade and encouraged through regulation, accreditation and education. Why is there such a contrast between areas of the world with equally high medical care? What have we done right in our RANZCOG community that others have not achieved?

One of the great differences between medicine in the US compared to those domains that practice high levels of single embryo transfer is the funding by the state for assisted reproduction. In Australia and New Zealand, there is significant Federal funding for IVF cycles, which substantially reduces the cost to the patient of going through this treatment. This encourages patients to take fewer risks because if they do not become pregnant on a single embryo transfer, they can use the frozen embryos on subsequent cycles without exorbitant expense. Even in New Zealand, which is not quite as generous in its funding as Australia, there is a very high degree of single embryo transfer. Various countries in Europe also mandate single embryo transfer as a condition for generous publicly funded cycles. There is now abundant evidence that transferring embryos singly does not compromise the overall pregnancy rate, while reducing multiple pregnancy rates to very low levels.2

A second reason for the high prevalence of single embryo transfer in key countries has been the advocacy by professional groups to educate patients and to encourage practitioners to practice single embryo transfer. In the 1990s, clinics in Sydney and Adelaide started to do single embryo transfer electively and a randomised control trial, the Asset Study, conducted across several clinics led to information that increasingly persuaded patients that double embryo transfer was not safe for them. The rapid change from double to single embryo transfer occurred in the absence of any regulation or coercion from government authorities and was voluntarily incorporated into the RTAC guidelines by which clinics are accredited. It is now impossible for patients to shop around to find a clinic that will give them two embryos when all the others are offering a single embryo transfer.

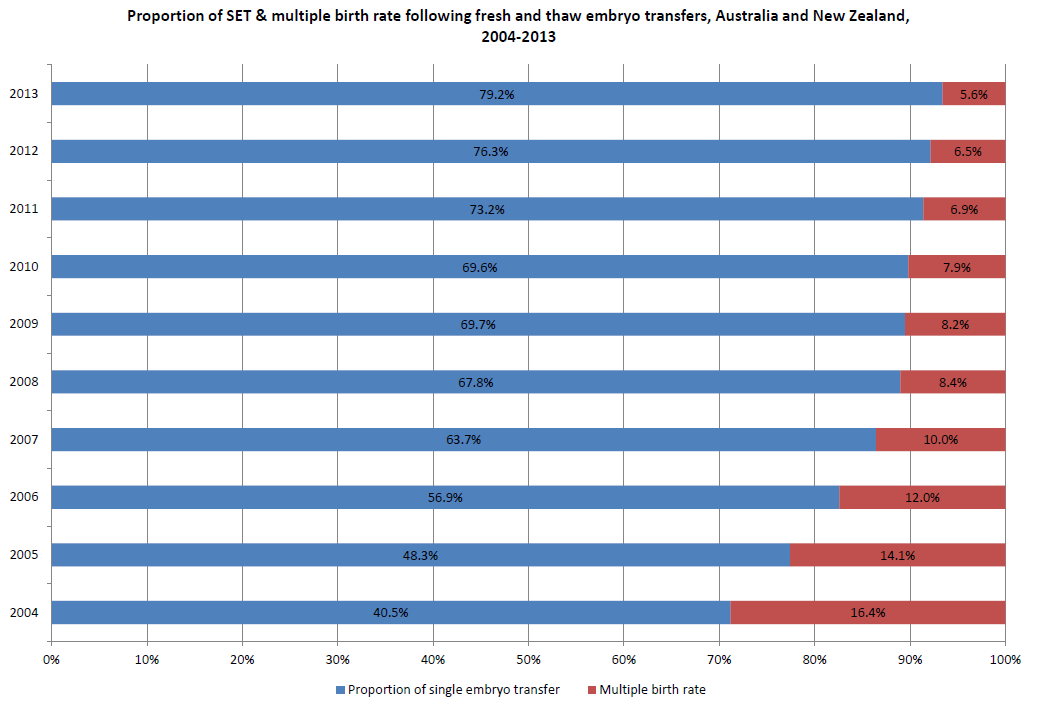

The multiple pregnancy rate now is below six per cent in Australia, which is remarkable and is only equalled by Sweden (see Figure 1). This is aided by the increasing success of freezing embryos and their excellent, sometimes superior, pregnancy rates compared with fresh embryo transfer. This has led to an increased confidence in encouraging patients to accept single embryo transfer, even at later ages, knowing that the pregnancy rates for the cohort of embryos after using them all will be the same regardless of single versus multiple transfer, but with a very small multiple rate if single transfer occurs.

Figure 1. Reduction in IVF multiple pregnancy delivery rates in Australia and New Zealand (ANZARD data, courtesy Dr Georgina Chambers, UNSW).

Several problems remain, however. The first is the problem of the older woman in whom implantation rates for an embryo are considerably reduced, owing to aneuploidy of the embryo. The common practice has been to offer a double embryo transfer to patients who are older than 38, with a maximum of three for women over 40, although this rarely occurs. This has led to unexpected multiple pregnancy rates in women where implantation rates are generally low. Similarly, double embryo transfer is sometimes practised when several transfers have occurred in younger women and again a multiple pregnancy can emerge unexpectedly.

Approaches to this problem generally run along two lines. The first is to always offer one embryo transfer regardless of age, bearing in mind that other embryos can be stored and used on a single embryo transfer in subsequent cycles. This, however, leads to frustration and increased expense for patients who are putting back embryos that may be aneuploid without any success. The second approach has become more popular recently and that is to do preimplantation genetic diagnosis on embryos from older women to identify those that are euploid and to only replace those singly. This is now becoming common practice in the US, where the resistance to single embryo transfer has disappeared with the advent of good preimplantation genetic screening services in every clinic. Indeed, many clinics are now going to the extreme of not putting any embryos back fresh, but biopsying all of the embryos before freezing them and then only replacing the euploid on a frozen cycle. Given that freezing is now so good and that frozen cycle implantation rates are as good as fresh, this would appear to be an attractive option. However, despite many thousands of babies born from preimplantation genetic diagnosis, safety data are lacking and there are very few, if any, randomised control trials that show the benefit of preimplantation genetic screening overall. Given the strong financial incentives in the IVF industry, it may take some time before we get substantial data to show whether it is beneficial or not.

A further problem is of monozygous pregnancies arising from single embryo transfer. These are clearly unpreventable, but have a very high risk of pregnancy complications. There has been a suggestion these are more common after blastocyst culture and transfer and it is possible that early transfer, such as at cleavage stage, may work better. However, selection of a superior embryo for implantation is more difficult at this stage. New technologies – such as metabolomics of the culture media, continuous imaging of the embryo development and evaluation of microRNA from the embryo – remain to be shown to be valuable.

Other problems remain in reproductive medicine relating to multiple pregnancy. Ovulation induction with clomiphene, letrozole and follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) is still widely practised and unless monitored carefully, can lead to multiple ovulations and increased multiple pregnancy rates. The practice of intrauterine insemination (IUI) using FSH is still used in Australia and there have been several well-publicised cases of women producing more than one fetus on IUI, including one woman who had ten children in two IUI and one IVF pregnancies. In the strong belief that multiple pregnancies are not ideal, many practitioners have virtually abandoned ovulation induction to use IVF, which they believe is better for their patient in terms of speed and reducing the multiple pregnancy rate and, at the same time, is more financially advantageous for clinics. This has led to underskilling of our new trainees in reproductive medicine in ovulation induction, leading to earlier use of IVF than is required if an experienced practitioner had used monitored oral drugs or gonadotrophins instead. Most experienced practitioners of FSH ovulation induction report multiple pregnancies to be around the rates of single embryo IVF.3

Responses to the ‘Octomom’ news ran the gamut: from academic papers and political discussion to salacious stories, and pictures, in the gutter press.

Australia and New Zealand have led the way in the world in responsible practises in IVF, particularly relating to the use of single embryos. Any unravelling of the financial incentives for patients to practice this will lead to a rise in multiple pregnancy rate and corresponding implications for health costs and safety.

References

- Sullivan EA, Wang YA, Hayward I, Chambers GM, Illingworth P, McBain J, et al. Single embryo transfer reduces the risk of perinatal mortality, a population study.

- McLernon DJ, Harrild K, Bergh C, Davies, MJ, de Neubourg D, Dumoulin et al. Clinical effectiveness of elective single versus double embryo transfer: meta-analysis of individual patient data from randomised trials. British Medical Journal. 2010; 21 341:c6945.

- Norman RJ. ‘Does ovulation induction with follicle-stimulating hormone still have a future in polycystic ovary syndrome? Fertil 2012; 98(3):599.

Leave a Reply