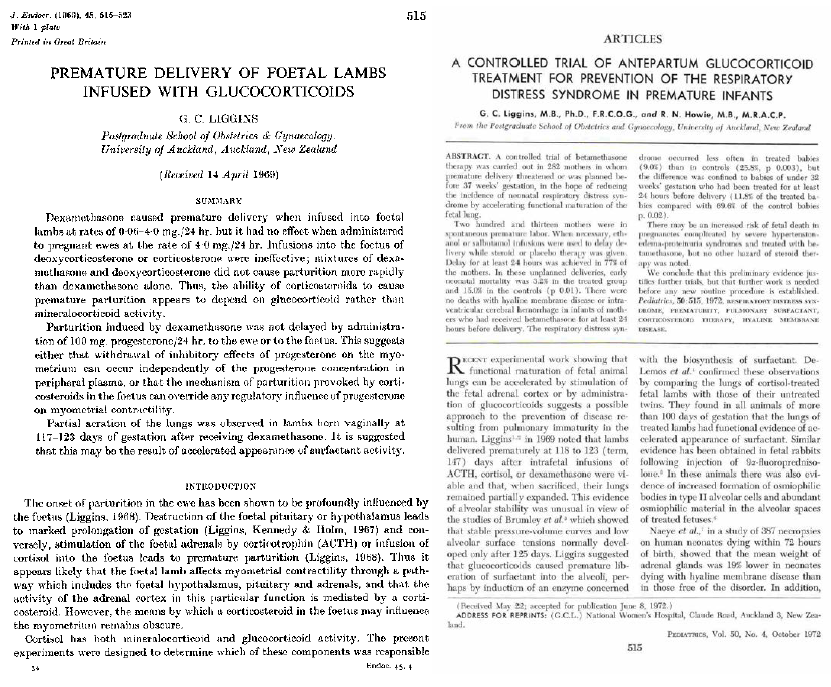

In 1972, Mont Liggins from National Women’s Hospital in Auckland, and his neonatologist colleague, Ross Howie, published a paper in Pediatrics that fundamentally changed the face of modern perinatology.1 They reported that mothers who were in premature labour and who were given antenatal betamethasone delivered children who had a significantly reduced risk of respiratory distress syndrome or hyaline membrane disease. At that time, immaturity of lung function was the primary concern of the emerging field of neonatology; respiratory care was in its infancy and survival rates for infants below 34 weeks of gestation were rather low. This finding was to dramatically change clinical perinatology.

Liggins was born in 1926 in a small provincial town near Auckland. His preferred name, Mont, came from a cartoon character that he had been immensely fond of as a little boy and no one called him by his proper name. He had graduated from medical school in Otago in 1949, and then trained in Newcastle on Tyne in obstetrics and gynaecology. He and soon-to-be his wife, Celia (1928–2003), met while applying for the same post and, fortunately, they were both appointed. In 1959 they returned to Auckland, Celia to enter private practice and Mont to join the fledging academic unit at National Women’s Hospital in Auckland. Here there was another soon-to-be hero of translational obstetrics, Bill (later Sir William) Liley, who was conducting studies that led him to undertake the first successful intrauterine intraperitoneal transfusions of blood to treat fetal haemolytic anaemia caused by Rh incompatibility. Liggins worked with Liley on these early studies and, with his characteristic inventiveness, developed a self-retaining catheter for use in pregnant sheep2 – an experimental system that Mont was to use to launch a remarkable career.

Liggins decided to focus his own career on what he then saw as, and still remains, the biggest challenge in obstetrics: premature labour. He took his cue from observations that cows with hereditary pituitary dysplasia had prolonged pregnancies. At the University of California at Davis, he studied sheep that also had prolonged gestation as a result of eating a lily containing the alkaloid jervine early in pregnancy. These fetuses were also malformed with hypothalamic and pituitary dysplasias. Liggins returned to New Zealand determined to explore the biology of this relationship experimentally. He developed techniques to remove pituitary or adrenal glands of the sheep fetus and showed that these pregnancies were prolonged. He then showed that he could reverse this effect, as well as accelerate birth by infusing corticotropin (ACTH) or glucocorticoids into the normal fetus.3

It was a serendipitous observation from this set of studies that was to change the path of neonatology and place Liggins at the forefront of perinatal science of the 20th century. It was already known from US research in the 1960s that the core deficit in hyaline membrane disease (which had killed President John F Kennedy’s youngest son, who had been born prematurely in 1963, shortly before JFK’s assassination) was a lack of pulmonary surfactant in the fetal alveoli. This lack meant the lungs could not maintain their opening at the end of expiration, so premature lambs died and at postmortem there was no air in their lungs. But in his 1967 studies of infusing the normal fetus with ACTH or cortisol to induce premature birth, Mont noted that a prematurely born lamb had died with air in its lungs.4 I suspect this incidental observation would have been ignored by most, but Liggins recognised the significance of this finding. He rapidly changed his emphasis to study the impact of fetal glucocorticoids on the maturation of the fetal lung.

Almost immediately, he launched a robustly designed, double-blind clinical trial of maternal betamethasone to women in premature labour, even though this type of clinical research had not really been part of his past experience. Ross Howie provided the neonatal expertise to assess the infants born in the trial. The results, published in 1972, were compelling, with more than a 50 per cent reduction in perinatal deaths.5 That study, supported by a number of similar studies that followed in other countries, became represented in the meta-analysis that still features on the Cochrane Collaboration logo. It is amazing to think that less than five years passed between the publication of the initial observation that glucocorticoids induced premature delivery in the sheep to the publication of the clinical trial of antenatal betamethasone. That speed of translation would be most unlikely, if not impossible, today.

While some centres rapidly adopted the use of glucocorticoids, scepticism for research not initiated in the USA meant that it would be another two decades before the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists was to endorse their use. Their effectiveness, safety and limits have been extensively reported and the original cohort has continued to be studied into the fourth decade of life by Prof Jane Harding of the Liggins Institute and her colleagues.

The title pages of the research papers that were to change the face of perinatology.

Liggins went on to explore, as did other groups, the mode of action of glucocorticoids on the fetal lung: they induced both surfactant production and changes in lung elasticity. He also explored other aspects of the regulation of fetal lung maturation, particularly the role of fetal thyroid hormones and TRH, as well as the effects of fetal breathing movements. The latter he showed in elegant experiments to promote lung growth.6 Indeed, Liggins had played a role in the rediscovery of fetal breathing movements – a phenomenon that had been observed decades earlier, but ignored, and which Liggins rediscovered while on sabbatical with Geoffrey Dawes in Oxford in 1969, simultaneously with a French group – this area of study would play an important part in the developing science of fetal neurophysiology throughout the 1970s and 1980s.

We now know that the antenatal rise in glucocorticoids is important for the maturation of a wide variety of biological systems in the mammalian fetus. Indeed, studies of the development of the fetal glucocorticoid system became a dominant focus of perinatal physiology for the next 40 years not only because of these effects on organ maturation, but also because of the link between the maturation of this system and the onset of parturition, particularly in ruminants. While the story in humans remains much more complex, Liggins’ work on parturitional biology was seminal to the development of an understanding of the role of the prostaglandin cascade in the onset of parturition. He demonstrated the role of prostaglandins in cervical ripening – again, work which has had long-term practical translation.

However, Liggins’s contributions were even broader. As a gynaecologist, he was involved in the first clinical trials of oral contraceptives in New Zealand. He was the first to suggest sequential packaging of the pill where inactive pills covered cover the withdrawal phase – an invention, he would wryly suggest that, had he known then about patents, would have made him a very wealthy man and could have forgotten about the nuisance of research grants. He found time with US colleagues to study the physiology of diving seals in the Antarctic, even though he had to deceive the medical examiner by providing his daughter’s urine to hide the fact he had developed type 2 diabetes.

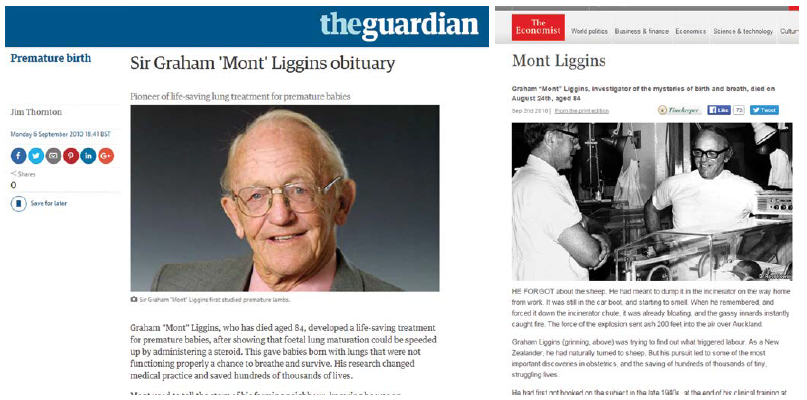

A figure of international stature, Mont Liggins’ life was honoured in newspaper headlines around the world.

As a young perinatal researcher returning to New Zealand in 1980, I found Mont’s unequivocal and generous support to be of critical importance. Indeed, he had a remarkable enthusiasm and generosity of ideas for young scientists. By then he was running his experimental flock of sheep on a park in central Auckland. He gladly welcomed me to share the flock. Monday mornings were spent doing the husbandry and Mont would palpate the sheep and pronounce with remarkable accuracy as to their gestational length and whether they carried twins or singletons. He was, however, less accurate when it came to ear-tagging them – I carry a permanent scar where he managed to tag my hand rather than the sheep! Alongside sharing the flock, we shared the fetus: he took the lungs and allowed my group to study other aspects of fetal physiology. Often I would be excited about some result only to find Mont had already done the experiment; Mont, in his classic style, only ever published a fraction of what he had done.

The deserved honours came – he was elected FRS in 1980 and knighted in 1991. Many in the perinatal community were saddened that his work, which has saved so many lives, was not recognised by the Nobel committee despite considerable lobbying. In 2001, the University of Auckland recognised his contribution by establishing the Liggins Institute, dedicated to perinatal research.

Mont never had the ambition to grow a large group and certainly avoided university administration (and knew how to defeat– or was it to deceive? – every university accountant who came near his grants as to whether they were in funds or otherwise). Mont retired early in 1987 to avoid the challenges of university bureaucracy, but he continued in full-time research supported by his superannuation, his forestry business and his wife’s clinical practice. It was more than a decade later before illnesses for both Celia and Mont caught up with them.

He was passionate about the role of the National Women’s Hospital as a global centre of academic obstetrics and was devastated by the events that unfolded in the 1980s. In between, he was busy with many practical projects: his fishing, his yachting, his forestry and, most of all, supporting and enjoying his beloved family. Even when he was ill, his good humour and his interest in good science always came through. This was a man who knew how to take the most from his life, but he gave back so much more. Mont died in 2010.

Acknowledgements

This piece draws on a more extensive biography in the Biographical Memoirs of the Royal Society that acknowledges the sources for this brief tribute: http://rsbm.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/roybiogmem/early/2013/03/28/rsbm.2012.0039.full.pdf

References

- Liggins GC, Howie RN. A controlled trial of antepartum glucocorticoid treatment for prevention of the respiratory distress syndrome in premature infants. 1972;50:515-25

- Liggins GC. A self-retaining catheter for fetal peritoneal transfusion. Obstetrics and 1966;27(3):323-6.

- Liggins GC. Premature parturition after infusion of corticotrophin or cortisol into foetal lambs. Journal of Endocrinology. 1968;42:323-9.

- Liggins GC. Premature delivery of foetal lambs infused with glucocorticoids. Journal of Endocrinology. 1969;45:515-23.

- Liggins GC, Howie RN. A controlled trial of antepartum glucocorticoid treatment for prevention of the respiratory distress syndrome in premature infants. 1972;50:515-25.

- Liggins GC, Vilos GA, Cammpos GA, Kitterman JA, Lee CH. The effect of bilateral thoracoplasty on lung development in fetal sheep. J Develop Physiol. 1981;3:267-74.

Leave a Reply