At least one-in-seven new mothers and one-in-ten pregnant women in Australia will experience perinatal depression. Data on perinatal anxiety are less reliable; however, perinatal anxiety is thought to be at least as common as depression and many women experience both anxiety and depression. Fathers are also affected by perinatal anxiety and depression. The most recent data available from the Australian Institute of Family Studies suggest as many as one in ten new fathers will experience postnatal depression. We have recently had the opportunity to review data from the first five years of the Perinatal Anxiety & Depression Australia (PANDA) Helpline. The results, together with insights from our dedicated helpline team, present a compelling picture of this common and serious health issue that, in our view, is not discussed openly or often enough.

While PANDA has existed in Victoria for almost 30 years, the National Helpline only began in 2010. We have now managed more than 50 000 calls through the Helpline. PANDA is committed to sharing the essence of the stories we hear each day to improve service provision. There is one overwhelming message from the many conversations we have each week. Expecting and new parents do not anticipate perinatal anxiety or depression will affect them and, as a result, they are slow to recognise the symptoms, slow to seek help and, therefore, suffer longer than they need to.

With help, most women will fully recover from perinatal anxiety and depression. Obstetricians are well placed to help women anticipate and understand changes in their mental health. Understanding what is happening to them allows women to seek help early. This is important not just for the woman, but also for her baby and other family members.

PANDA Helpline

Calls to the PANDA Helpline cover the whole spectrum of emotional health and mental illness. While many calls focus on difficulties associated with the transition to parenthood and low-level anxiety and depression we also deal regularly with acute mental illness and crisis-intervention calls.

PANDA’s counselling team is an integrated workforce of professional counsellors and highly trained volunteers. To respond effectively to the diverse range of calls, all staff are trained in dealing with suicide prevention, domestic violence and trauma from childhood abuse. Importantly, PANDA’s service is more than an incoming helpline. For callers with mild-to-moderate perinatal anxiety and depression we also offer a follow-up service. This is a particularly important service given the volatile nature of the perinatal period.

Who calls PANDA?

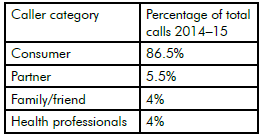

While most calls to PANDA are directly from women experiencing perinatal anxiety and depression, the calls are also from partners (5.5 per cent), other family members and friends (four per cent) and the remaining four per cent from health professionals (see Table 1). PANDA’s team welcomes calls from health professionals to consult about a patient or provide referral options and resources.

Table 1. Who calls Panda: by category.

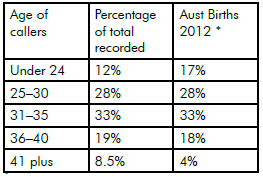

Table 2 compares age of callers with the average age of birth in Australia. Younger mothers are under-represented in our callers and older mothers somewhat over-represented. We know that older mothers often have a complex journey to birth (such as miscarriage, IVF or birth trauma), which is a recognised risk factor for perinatal anxiety and depression.

Table 2. Who calls Panda: by age range.

*Australian Mothers and Babies, AIHW, 2012

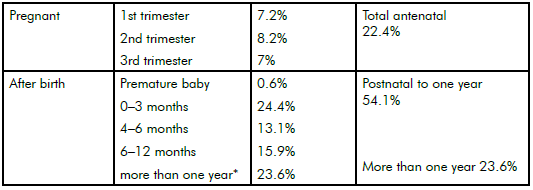

Most calls are from women in the postnatal period. We would like to see an increase in calls from women during pregnancy. The group calling more than one year after the birth includes those who have delayed treatment and those still recovering. This category also includes callers who may have been triggered by our awareness-raising activities and are understanding for the first time that there is a name for the experience they had in the past.

Table 3. Who calls PANDA: by stage of pregnancy/time after birth.

*Includes callers reflecting on a much earlier experience

While the great majority of callers to PANDA are women, there is an encouraging increase in recent years in the number of male callers. This increase is linked to two factors, firstly PANDA’s direct efforts to increase male callers, including the launch and promotion of howisdadgoing.org.au, a website specifically targeting new fathers and, secondly, a change in clinical practice whereby helpline staff routinely ask about how the non-calling parent is managing and encourage them to call if they need assistance. Of the male callers, most (65 per cent) are calling about their concerns for their partner while 35 per cent are calling about their own experience of depression or anxiety. Callers come from right across Australia, although there remains a small over-representation in Victoria. At just 13.5 per cent of PANDA’s callers, Queensland is under-represented. To match Australian population data this figure should be closer to 20 per cent.

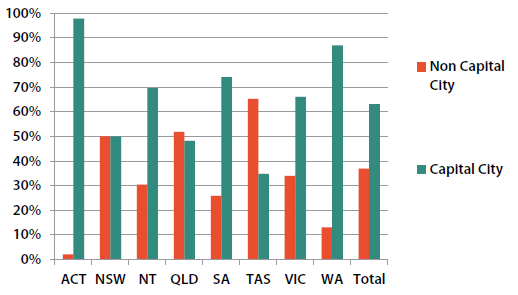

Figure 1 shows the spread of callers across capital city and non-capital city areas. Representation of rural callers in Victoria and NSW exceeds population average and in Queensland, Tasmania and South Australia it closely matches population. There is room to improve rural access in Western Australia and the Northern Territory.

Figure 1. Caller location by region.

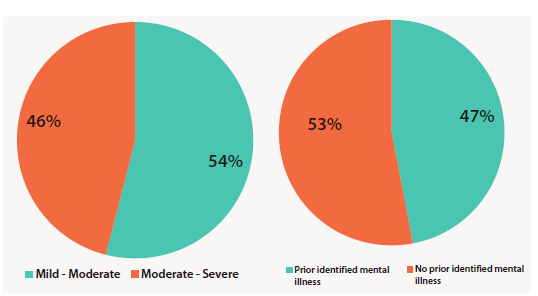

Most callers to PANDA do not have a specific diagnosis of perinatal anxiety and depression and PANDA does not diagnose a caller’s mental health status. PANDA’s general assessment process shows 54 per cent of callers with mild-to-moderate anxiety or depression and the remaining 46 per cent in the moderate-to-severe category (see Figure 2). Caller needs range from simply seeking information and reassurance to immediate crisis intervention.

Figure 2. Callers by severity of depression (left) and history of mental illness (right).

While 53 per cent of callers had no prior identified mental illness, 47 per cent identified a previous history of mental illness (see Figure 2). We know that previous mental illness is a risk factor for perinatal anxiety and depression, but previous mental illness is over-represented in PANDA callers. It is probable that these callers have been able to identify their declining mental health and may be confident in seeking help given their prior experience of mental illness.

Emotional well-being in pregnancy is important to consider and respond to. At least one-in-ten expecting mothers will experience antenatal depression or anxiety. While it might be normal for an expecting mum to feel sad or a little anxious about pending parenthood, symptoms of depression or anxiety that persist for more than two weeks should be addressed. Of women diagnosed with postnatal depression or anxiety at 12 weeks post-birth, 40 per cent report having experienced symptoms antenatally.3 There is an opportunity to ensure these women get help sooner rather than later.

Try to make the time and create the space to check in on your patients’ mental health and emotional well-being as well as their physical health and well-being. Early intervention reduces suffering and gives the baby the best chance of thriving. In some cases, at the most serious end, early intervention can save lives. In particular, watch out for signs of anxiety. Perinatal anxiety is less well understood than depression. An expecting mother’s distress during pregnancy can affect the baby’s development and also the birth experience. Traumatic birth experience is a risk factor for postnatal mental illness. It is also important to note that, while many expecting mothers have heard of postnatal depression, many do not understand that antenatal depression is almost as common.

Previous mental illness is a significant risk factor for perinatal anxiety and depression, so it is important that women with a history of mental illness are effectively monitored for perinatal anxiety and depression during their pregnancy and after the birth. Make sure you know about any history and check in regularly with patients about their mental health. Refer any patient with a history of mental illness who is presenting with symptoms that are affecting functioning to a perinatal psychiatrist for review and management before the birth.

You can contribute to breaking down the stigma attached to mental illness by routinely asking questions about your patients’ mental health. Given the volatile nature of the perinatal period, it is important to check in regularly with patients about their mental health. With increasing understanding of the direct and indirect impact of perinatal anxiety and depression on expecting and new fathers, you might also attend to signs that the male partner is struggling.

Have perinatal anxiety and depression resources available in your practice. This will also help normalise the experience so that your patients can talk about it and seek help. You and you staff are welcome to contact PANDA for specific advice and for resources.

PANDA Helpline 10am – 5pm EST

Monday to Friday

1300 726 306

www.panda.org.au

In addition to receiving incoming calls, PANDA is able to provide a callback service to support women through this difficult time. The service is free and confidential. No referral is necessary. PANDA has an extensive referral database and is able to make sure callers are linked to local services. Obstetricians are welcome to call the PANDA Helpline for secondary consultation or general advice.

Lessons learned

Perinatal anxiety and depression doesn’t discriminate – it affects women from across the socioeconomic spectrum. Many women are reluctant to seek help or simply don’t understand what is happening to them. Of callers to the PANDA Helpline, 65 per cent report having symptoms for more than four weeks before, including 15 per cent who have had symptoms for more than a year.

Callers often feel a deep sense of shame or judgement – this is commonly coupled with a view that they don’t deserve to be a parent/are a bad mother. For some, this leads to thoughts that someone will take their baby away if they talk about how they are feeling. Sometimes, women believe their family will be better off without them.

Our callers often do not tell their primary health professionals about their experience of perinatal anxiety and depression: 71 per cent of callers in our most recent audit period had not told their GP about their symptoms before calling the Helpline.

Grief and loss are significant contributing factors to perinatal distress. More than 50 per cent of callers say these experiences including IVF, miscarriage, stillbirth, relationship breakdowns and complex trauma) contributed to their capacity to be present in their pregnancy or to their baby.

The most important lesson we have learned is that seeking help early is the best option to help women recover and develop a healthy relationship with her baby. Many women need help to understand what is happening to them and encouragement to seek treatment. Letting a patient know that perinatal anxiety and depression is very common and treatment is available is a powerful step.

References and further reading

- All service data reported in this article is drawn from PANDA Client Data Package (CSS).

- Australian Mothers and Babies, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2012.

- Austin M-P, Antenatal Screening and early intervention for perinatal distress, depression and anxiety: Where to from here? Arch Women’s Mental Health. 1-6, 2004.

- beyond blue, Clinical Practice Guidelines; Depression and related disorders – anxiety, bipolar disorder and puerperal psychosis in the perinatal period, 2011.

Leave a Reply