Coming to a new country demands the willing surrender of a life well understood. To choose instead to embrace the unknown – the unknowable – and place at stake one’s future and one’s children’s future, on the hope of one singular venture. It requires the recreation of a person’s very identity – to become a mixture of something old and something unfamiliar – the only certainty is that you can never be the same as that person who would have stayed behind. It necessitates learning to accept of a wave of change: to familiar traditions, boundaries and expectations. To migrate is to let go and to fall through the looking glass, to embark upon an alternative life in which each quotidian act becomes a contest of patience and will.

Australia is a nation of over 300 languages. One-in-four Australians were born overseas and 60 per cent of Australia’s future population growth will come from migration. More than a million Australians have migrated here in the past five years. On top of this, nearly 1.7 million people are currently living and working here temporarily.1 Equally, as our population has rapidly diversified, the number of patients who do not speak English well or at all has grown dramatically.2 For the medical profession, the proliferation of complex cultural cases presents rising and unprecedented demands on time and resources.

Compared to Australian-born women, migrant and refugee women from non- English-speaking backgrounds experience higher rates of illness and health disadvantages. After living in Australia for five years, the average health of many migrant and refugee women has declined, despite increases in the general standard of living;3 suggesting that access to care is a key factor. Furthermore, migrant and refugee women are under represented in use of preventative health services and over represented in the acute and crisis setting. A lack of health system literacy and knowledge of how to navigate Western consumer-model health services sharply limits the access of a growing number of new Australians.

Lack of access is compounded by gender inequality. Increasingly, our migration program sources from countries with very different norms with regard to the role of women and their place in society. Domestic violence rates among immigrant communities are higher than the national average while, of concern, the reporting rates are significantly lower. Across every indicator of gender equality, migrant women are losing out: their participation in the workforce is well below migrant men, English language acquisition is lower and literacy and access to education is lower still.

The inequality facing refugee women, in particular, is further exacerbated by their pre-migration experience. Many have fled places of conflict, where rape, sexual torture and slavery are used as weapons of war. Rates of sexual violence are rampant in refugee camps, leading to downstream sexual and reproductive health issues including increased risk of sexually transmitted infections, pregnancy and birth complications, and mental health consequences of trauma. Women from refugee backgrounds coming to Australia will often have no prior experience of Western medicine or Western birthing and antenatal practices and may find the application of technology and birthing interventions confronting.

Getting prepared for birth can be complicated when you are in an unfamiliar environment.

For practitioners, three key issues need to be kept in mind when treating women from migrant and refugee backgrounds: language, culture and gender dynamics.

As an illustrative case study, Aditi*, a recent migrant from India, was brought over on a spouse visa to honour an arranged marriage. Her prospective husband had already been living in Australia for ten years, having originally arrived on a student visa. Aditi had no English and very little formal education. Her family had struggled to bring together an appropriate dowry, complicating her marriage from the beginning. Subsequently, her husband and her in-laws began to harass her in order to extort an increased dowry. The form of this harassment included repeated physical abuse from her husband and psychological abuse from her sister in-law.

After a year she fell pregnant and saw the child as a blessing. Aditi hoped the child would help mend her troubled relationship and would bring some joy to her life. She wanted her children to grow up in a country able to provide the privilege of the education she had not herself received. When she told her husband of the news he beat her and demanded she undergo termination of pregnancy. Her friends advised her that Australia is not like India; if she told the doctor that she wanted to keep the child, they would not perform the termination.

Her husband escorted her to the pre- termination counselling session. When the doctor called her in, her husband stepped forward and stated he would translate for her. She sat in the room with tears flowing down her cheeks as her husband explained that she was upset because she did not want to be pregnant and that she wanted the baby gone immediately. The doctor engaged only with her husband. Aditi explained later that she had felt more powerless in that moment than she ever felt before in her life. She said in that moment she gave up hoping for herself and began to believe that everyone in this new world was on her husband’s side.

While Aditi’s story is one isolated experience, it demonstrates the problems and complexities that doctors face. From a practitioner’s perspective on the encounter, arranging to have a neutral interpreter in the room or being able to understand the background cultural dynamics in play are both significant hurdles to remedy, requiring further resources that are often simply not available. Simply put, Australia’s broader framework of healthcare delivery – encompassing everything from referral pathways and Medicare claims to continuing education and auxiliary services has not kept pace with our changing demographics. All the while, the consequences of overlooking cultural complexity upon safe and effective patient care have become too grave and too common to be ignored.

What can practitioners do?

Firstly, be mindful not to make assumptions. Speak to the patient, as their cultural background may or may not inform their personal beliefs and expectations. Particularly around childbirth and women’s health, a medicalised Western approach may be very unfamiliar. Furthermore, what may seem banal in terms of sensible health advice can conflict with cultural understanding, thus be difficult to follow or be misinterpreted. For example, it is not uncommon in certain communities to interpret medical complications, such as gestational diabetes, as a bad spiritual omen or curse. Be mindful of the presence and influence of other family members, including partners, and use judgment and intuition. It is easier to call family members back into the room once you have determined their presence accords with your patient’s wishes.

A new mother welcomes her baby.

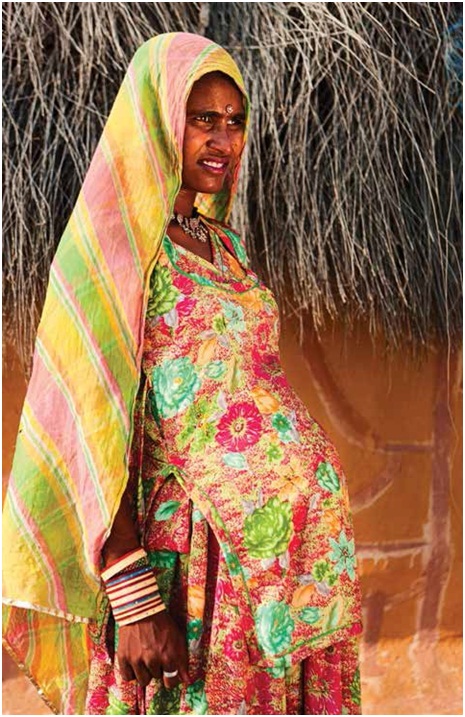

A pregnant woman in her village – becoming a migrant means leaving many cultural certainties behind.

Secondly, champion systems to identify who will need an interpreter ahead of time. In the public system, this may mean advocating for internal change. Raising demand from practitioners to improve the identification of patient language needs and provision of organisational resources for trained interpreters is a good start. In private practice, ensure your booking staff make note of a patient’s language skills, are able to assess if an interpreter may be required and, if needed, know how to arrange interpreter sessions. If the patient does not speak English, allow for extra time for the consultation.

Thirdly, when appropriate, involve migrant support services. There is a network of many settlement service providers around Australia with caseworkers trained to deal with cultural complexities. Not all migrants are eligible, but many of the most vulnerable and newly arrived patients are. Caseworkers themselves can offer independent support – they can chaperone clients to appointments, follow up dietary requirements, assist in filling prescriptions, monitor patient progress and advocate on their behalf. Not withstanding the limitations of patient confidentiality, settlement services bring dedicated cultural liaison skills to the table, and will be familiar with the process of arranging an interpreter on the patient’s behalf. The Settlement Council of Australia can provide details of your local settlement provider (www.scoa.org.au).

Finally, seek to learn about unfamiliar cultures as both a professional and personal interest. The better you understand your patients and their backgrounds, the more you will hear in their story, the better the questions you will ask and the stronger the chance you will have in your words being listened to and affecting change. If you are aware of a substantial representation of a particularly ethnicity in your community or clinic, take the time to get to know about the country and culture. It is an investment that will return tenfold in terms of improvement in patient relationships and patient care.

Obstetricians and gynecologists see women at a point of profound emotional vulnerability – fertility treatment, pregnancy, labour, menopause or an abnormal Pap smear. To imagine a woman seeking help in a foreign country, with no comprehension of what is being said, with no knowledge of the procedures, the machines or the tests to be run, lets us understand her personal ordeal as all the more daunting.

To be a migrant is to wear a badge of courage. We routinely trust our lives to doctors in an act of faith. For many migrants there is no such preconceived social conditioning – they have not grown up enduring dozens of visits to GPs for sore throats and sick notes or watched countless re-runs of ER. They have not lived in a culture where reverence to white coats and stethoscopes is the norm. To place their trust in you at a moment of the greatest vulnerability, where not only their life, but also their child’s life is in your hands is an act of great bravery. To spend a little more time and summon a little more patience is a small appeal in return.

*Name changed to protect identity. This interview was conducted on 25 May 2015.

References

- Australian Bureau of Statistics [Internet]. Migrant Families in Australia [updated 14 November 2013; cited 14 July 2015]. Available from www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/[email protected]/Latestproducts/3416.0Main+Features2Mar+2013#Current.

- 2 Department of Immigration and Border Protection [Internet]. Temporary Entrants and New Zealand Citizens in Australia [updated 30 September 2014; cited 14 July 2015]. Available from www.border.gov.au/ReportsandPublications/Documents/statistics/temp-entrants- newzealand-sep14.pdf.

- Department of Health [Internet]. Diversity – Ethnicity, Geographic Location, Disability, Sexuality [updated 7 February 2011; cited 14 July 2015] Available from www.health.gov.au/internet/publications/publishing.nsf/Content/ womens-health-policy-toc~womens- health-policy-social~womens-health- policy-social-det~womens-health-policy- social-det-diversity .

Leave a Reply