While an intern, I researched working in Africa, but was always asked if I was a specialist or had management skills or spoke another language. In the end, I gave up on the idea. I continued doing another two years residency, with 12 months of that focusing on obstetrics and gynaecology, and achieved my DRANZCOG in 1984. I then started working at family planning and general practice, eventually co-owning a general practice of seven female doctors with three female colleagues. I also worked three days a month in country South Australia as part of the Federal Government’s Rural Women’s GP service in 2002. Hearing about the poor status of women’s health in developing countries reignited my desire to focus some of my energies on improving this situation. I decided on two specific responses: I would endeavour to work in the field, but also put together a birthing kit that would be useful for mothers.

Working in the field

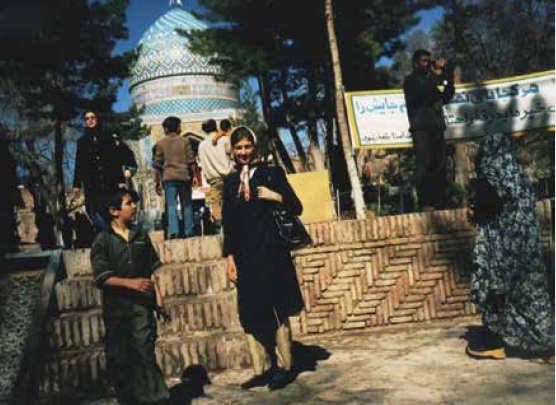

To prepare, I sold my share of the medical practice, did country work and brushed up on my French language skills. When offered a position with Medicins Sans Frontieres for six months in 2003–04, working with Afghan refugees in Masshad, Eastern Iran, I accepted.

Free health clinic services, medication and, if required, hospital treatment were provided to those refugees without means. Usually, 100–120 clients were seen by three to four doctors each four-hour session. Services were provided in a fixed clinic in Gulshar and mobile clinics temporarily set up in mosques or uninhabited houses.

I required an interpreter, Neshat, when interacting with patients, but luckily all the medical staff wrote their notes and spoke to me in English. I supported the midwife who provided antenatal care to patients. Bloods or other tests were performed infrequently. No smears were done and breast checks only if lumps were noted. During the six-month placement, I learned Farsi up to a grade 3 literacy level.

When I returned to Adelaide I commenced work as a locum. One of my first locums was with the Migrant Health Service in Adelaide where they provide comprehensive health assessments for new arrival refugees. The six months in Iran provided me with insights into the issues and realities that many of the refugees had experienced. Many women refugees arrived under the 204 visa category. This is the women-at-risk group, which often covers women who are head of households or widows and their families.

The groups I worked with were initially from Yugoslavia then from Sudan/Democratic Republic of Congo, then Iraq and Afghanistan. Now there are more Bhutanese and Burmese refugees, plus asylum seekers, many of whom are currently in community detention.

A small birth kit can make a big difference.

Birthing kits

In the late 1990s, I helped create a small one-use birthing kit that allows women in rural and remote areas of resource-poor communities to access items that ensure a clean and safe birthing environment. The kit contains a square metre of plastic, soap, a pair of gloves, pieces of string, a scalpel blade and gauze within a clip-lock plastic bag. It weighs less than 100g. The kits were originally financed, collated and sent by Zonta International clubs within the three Australian Districts 22, 23 and 24. Zonta International is a women’s service organisation, empowering women through service and advocacy. In 2006, the Birthing Kit Foundation Australia (BKFA) was formed to continue the work. I have been a board member since its inception. BKFA has provided 1.4 million kits free, mainly to non-governmental organisations that work with mothers in 28 countries. It has arranged for many more kits to be produced in the country. BKFA has also trained 9000 birthing attendants in Vietnam, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Ethiopia and India. In the last 12 months, BKFA has also organised three train the trainer programs in the Democratic Republic of Congo and India to increase the reach of education.

The knowledge I acquired doing obstetrics and gynaecology has been vital in performing my medical role. I, like many professionals working in health areas, hope to support people, especially women, in whatever way I am able, to achieve their optimal health and a full life.

The author on placement in Iran.

Leave a Reply