Gastroenteritis is a general term for any inflammation or infection of the gastrointestinal tract, but in common clinical usage it refers to episodes of nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea. In the general community, the usual causes of acute gastroenteritis are viral infections and bacterial food poisoning. The pathogen typically associated with outbreaks of infectious gastroenteritis in adults is norovirus. Episodic causes in adults include norovirus, but also commonly rotavirus and adenovirus. Infants often suffer from rotavirus in outbreak settings.

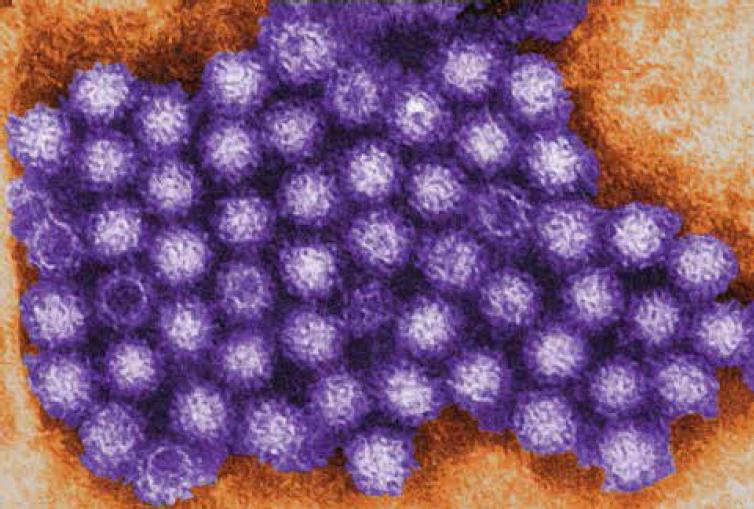

Noroviruses are non-enveloped single-stranded RNA viruses that belong to the Caliciviridae family. They are very infectious, with a single person often infecting as many as 12 other people. Noroviruses are classified into six genogroups of which G1, GII and GIV infect humans, most commonly GII. It is thought that the MDA-5 protein in humans is the primary immune sentry for detection of norovirus and individuals with common mutations of the MDA-5 gene seem to be more susceptible to infection by norovirus. When infection occurs the virus infects and replicates in the small intestine, leading to inflammation and onset of symptoms within a day or two. Although the infection is self- limiting, vulnerable people – the elderly or immunocompromised and children – are most vulnerable to dehydration and electrolyte disturbances, and deaths still occur from acute norovirus gastroenteritis.

In the initial stages of illness, it can be difficult to determine whether gastroenteritis is viral or from bacterial food poisoning. However, some features may help distinguish between the two. Food poisoning is typically associated with diarrhoea, abdominal cramping and vomiting, and fever may be present. Viral gastroenteritis is less likely to cause significant fever or bloody diarrhoea.

Norovirus gastroenteritis has a typically sudden onset of nausea and vomiting. The vomiting can be profuse and violent, occurring without warning and many times during a day. There is associated malaise, headache, myalgias and sometimes fever, and watery diarrhoea can also occur. Fortunately, these symptoms are relatively short lived, lasting only one or two days. Although diagnosis can be made using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing of faecal samples, this is more useful at a community public-health level than for individual cases and is not performed for routine diagnosis.

Norovirus infection is highly contagious, with direct transmission from person to person, airborne spread by aerosolised vomit, ingestion of food or drink contaminated with norovirus, and contact with contaminated surfaces or objects. It is generally stated that people are infectious from the day that symptoms commence. Viral shedding, however, can occur before symptoms begin and can persist for two or more weeks after the acute illness ends. It is not known whether viral shedding is indicative of infectivity. To reduce the risk of infection to others, it is usual to be excluded from work until there has been no diarrhoea for 24 hours.

Transmission electron micrograph (TEM) image of some of the ultrastructural morphology displayed by norovirus virions, or virus particles. Image credit: Charles D. Humphrey, courtesy of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Differential diagnosis

Common things occur commonly and the typical picture of acute onset of symptoms in a previously well woman, often during a period of community outbreak and with other family members or contacts affected with the same illness, points strongly to viral gastroenteritis. However, in pregnancy it is important to consider other causes (see Box 1). Food poisoning typically occurs within a few hours of ingestion and may simultaneously affect others sharing the same food. Surgical causes often have vomiting without the associate nausea. Emerging infections such as Clostridium difficile colitis may be difficult to exclude clinically if there is concomitant hyperemesis and can occur without clear antibiotic exposure. Pregnancy-specific conditions – hyperemesis, acute fatty liver and severe pre-eclampsia – will have their own symptom complex.

Assessment

Dehydration is assessed by clinical examination, looking for reduced skin turgor and dry mouth and tongue. There is commonly tachycardia and postural hypotension, though these can be more difficult to interpret in pregnancy. The fetal heart should be auscultated. There is little role for investigations if the clinical history is clear, but electrolytes and renal function and full blood count might be assessed. To distinguish from pregnancy-specific causes, checks of uric acid and liver function might be made. Acute fatty liver is characterised by low blood glucose levels, high white cell count and abnormal liver function.

Treatment

There is no specific treatment for norovirus infection in pregnancy and, unfortunately, no vaccine available. Oral rehydration and parenteral or oral antiemetics (metaclopramide or ondansetron) are the mainstays of treatment. It is important to manage pregnant women as outpatients if possible, as norovirus infection can sweep quickly through a maternity ward and affect neonates. For women who are not tolerating oral rehydration, intravenous fluids may be required. Strict infection- control procedures should be in place, including meticulous attention to the five moments of hand hygiene.

Hepatitis A

Recent cases of hepatitis associated with imported frozen berries have drawn attention to hepatitis A. Hepatitis A virus (HAV) is a small RNA virus, or picornavirus. It is not enveloped and, like norovirus, contains a single strand of RNA enclosed in a protein shell. Although HAV has only one serotype, there are many different genotypes; four of which affect humans, the commonest of which is the IA subtype.

HAV spreads by the faecal-oral route and is common where there is overcrowding with poor hygiene and sanitation. HAV is very hardy and is resistant to the action of detergents, desiccation and high temperatures. For this reason, HAV can survive for long periods in water. Fortunately, chlorination of drinking water is an effective way of inactivating the virus. Infection is common in the developing world (where it approaches 100 per cent) and usually occurs in early childhood. In Australia, childhood infection is uncommon except in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population in Queensland, Northern Territory, South and Western Australia. For this reason, it is included in the National Immunisation Program Schedule for those aged 12–24 months from these high-risk populations. Parenteral transmission, for example by blood products, is now very rare. Outbreaks associated with food such as shellfish are common, particularly if the shellfish have been sourced from polluted waters.

Once ingested, the HAV particles cross into the circulation through the digestive mucosa and are carried to the liver by the portal circulation. HAV infects hepatocytes and liver macrophages, and then multiplies with cell breakdown and release of new HAV particles through the bile into the faeces. Unfortunately, infected individuals often excrete large numbers of infectious HAV in the stool for more than a week before the onset of symptoms. Therefore, people infected with HAV can be infectious before there is a recognisable onset of symptoms and for almost a fortnight after the acute infection has passed. The incubation period is long, averaging a month, meaning that the source of infection may be long forgotten, making source tracing difficult.

Clinical presentation

The initial symptoms of acute hepatitis A are non-specific with an influenza-like illness or, in some cases, few symptoms at all. The illness can last for up to two months, but sometime considerably longer. Typical presentation is with jaundice, dark urine, anorexia, low-grade fever, fatigue, nausea and diarrhoea with light (clay coloured) stools. You are more likely to experience symptoms the older you are at the time of infection.

Diagnosis is based on clinical suspicion and isolation of IgM against HAV. If the test is negative at initial presentation, a four-fold rise in HAV IgM is also diagnostic (presence of IgG suggests that the infection is not acute). There may be an increase in serum ALT levels. There is no treatment for hepatitis A, apart from avoidance of alcohol (which is often poorly tolerated), healthy diet (avoidance of fatty foods) and good hydration. There is no particular risk to the fetus in pregnancy, but it is important to distinguish acute hepatitis A from other causes, including pre-eclampsia, HELLP syndrome and acute fatty liver. For women with a significant travel history and jaundice, hepatitis E is important to exclude as fetal risk includes spontaneous abortion and premature delivery. Maternal liver failure can also occur. The mortality rate from hepatitis A in otherwise healthy people is very low.

An effective vaccination against HAV is available and recommended for those at risk. The vaccination contains a live, attenuated virus, so should not be given in pregnancy.

Box 1. Differential diagnosis of acute nausea and vomiting in pregnancy

General

- Acute viral gastroenteritis

- Acute bacterial food poisoning

- Clostridium difficile colitis

Pregnancy specific

- Severe nausea and vomiting of pregnancy (hyperemesis gravidarum)

- Acute fatty liver of pregnancy

- Severe pre-eclampsia

Non-infectious

- Ovarian torsion

- Surgical causes – acute cholecystitis, appendicitis, small bowel obstruction, pancreatitis

- Hepatitis

- Diabetic ketoacidosis

Leave a Reply