In the era of very advanced maternal age, what do we know and what is yet to be determined?

Before the development of donor oocyte therapy, the upper limit of reproductive age for women was determined by low conception rates once women were over the age of 40. Advanced reproductive technologies, introduced as treatments for infertility and premature ovarian failure, have now been increasingly used to assist perimenopausal and postmenopausal women to achieve pregnancy. This has led to uncharted territory when it comes to pre-pregnancy risk assessment, antenatal care and peridelivery management. Medium- and long-term outcomes for these women and their offspring remain largely undetermined.

Epidemiology

It is estimated that there were around 2000 donor oocyte cycles performed in Australasia in 2010, with nearly 30 per cent of recipients being over 45 years of age. Australasian women also seek donor oocyte and embryo treatment overseas, with estimates of more than 500 babies born each year in Australasia following conception with donated oocytes from overseas.1

The rates of donor oocyte cycles provided to woman over the age of 50 years in the USA have more than doubled between 1998 and 2010.2 The popularity of this treatment is driven by the increased chance of a successful live birth; with women over 45 years of age having an over 50 per cent success rate compared to 1.8 per cent success rate using their own oocytes.3

It is likely that increased recipient age over 45 years is associated with small, but progressive, declines in favourable reproductive technology outcomes (implantation, clinical pregnancy, live birth and miscarriage), compared to outcomes for younger recipients. Live birth rates remain high in the age cohorts over 45 years – 52.7 per cent and 48.6 per cent for women aged 45–49 and >50, respectively.4

Outcomes of pregnancy

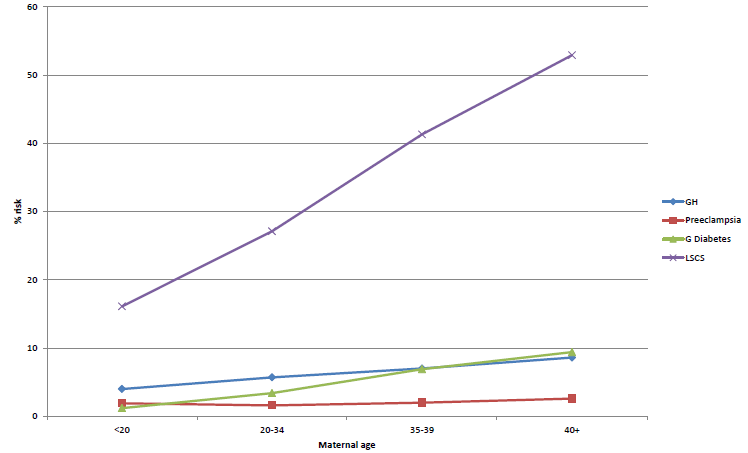

The Canadian Institute for Health information has reported outcomes across maternal age groups for primigravida singleton pregnancies that indicate increasing risks with age, especially for delivery by caesarean section (see Figure 1).

While there is a progressive impact of advanced maternal age over 35 years on pregnancy outcome, there is a remarkably small volume of outcome data for women of very advanced maternal age (VAMA, defined as>45 years) in either the Australasian or international literature. The more recent information that exists pertains increasingly to outcomes from donor oocyte programs. Most series are of limited size and therefore report only frequent outcomes such as gestational diabetes, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, preterm delivery, mode of delivery and rates of small for gestational age babies (see Tables 1–3). It is not possible to determine the risks of less-frequent maternal and neonatal outcomes, such as maternal and neonatal death, postpartum caesarean section, placenta accreta/percreta and maternal cardiac events.

The literature reports a wide range of risk of adverse maternal outcome and therefore makes it difficult to predict outcomes for pregnancy in women over the age of 45 years. It is not possible The literature reports a wide range of risk of adverse maternal outcome and therefore makes it difficult to predict outcomes for pregnancy in women over the age of 45 years. It is not possible to determine that ‘pre-screening’ women for medical suitability for pregnancy reduces the risk of maternal adverse outcomes.

Figure 1. Pregnancy outcomes by maternal age – Canadian Institute of Health.20

There are two reported episodes of maternal death in women over the age of 50 years after donor oocyte therapy. One death occurred from intracerebral haemorrhage in the setting of HELLP syndrome14 and one occurred from acute cardiac arrest.15

The largest report of outcomes for pregnancy in advanced maternal age (>40) from California described the outcomes of more than 24 000 pregnancies between 1992 and 1993. They described a pre-eclampsia rate of 5.4 per cent and a gestational diabetes rate of seven per cent in nulliparous women.16

The literature confirms the high rates of delivery by caesarean section in VAMA pregnancies. The underlying reason for this high rate may be influenced by rates of multiple pregnancies following fertility treatment, concerns regarding maternal age and post-dates delivery and neonatal concerns.

Adverse perinatal outcomes are increased in all series compared to outcomes of pregnancy in woman of lower maternal age. Rates of preterm birth are elevated and SGA is high in most studies. This represents a higher risk of neonatal unit admission, prolonged neonatal hospital stay and potential for medium- and long-term medical complications during childhood. Donor oocyte therapy is associated with high rates of multiple pregnancy (15–39 per cent), which is associated with an increased risk of maternal and perinatal adverse outcomes.19 The high rate of multiple pregnancy could be reduced substantially by adhering to recommendations to avoid transfer of more than one embryo at a time, when oocyte donors are of a younger age.22

Although the immediate outcomes of VAMA pregnancies are reported in small numbers, there is a lack of follow-up data to answer very important questions:

- Is there a higher risk of poor recovery from pregnancy complications for these women? This is particularly relevant for hypertensive and diabetic complications, which are known to potentially predict future development of cardiovascular and metabolic disease.

- What is the risk of rare but serious complications that could be associated with advanced maternal age? These potential complications may include peripartum cardiomyopathy, pregnancy related myocardial infarction, venous thromboembolism, and placenta accreta or percreta.

- What are the long term outcomes for children born to women of VAMA? We might expect an increase in complications already recognised as higher risk in adults who were born prematurely or SGA.

Table 1. Maternal outcomes in VAMA.

| Author | Country | Year | n | IVF only | Hypertension | Preeclampsia | GDM | Age |

| Jacobsson17 | Sweden | 1987–2001 | 1205 | no | 3.4% | 2.2% | 4.7% | >45 |

| Paulsen5 | USA | 1991–2001 | 40 | yes | 35% | 20% | >50 | |

| Sauer18 | USA | 1990–1994 | 74 | yes | 11% | 2.7% | 8.1% | >45 |

| Sheffer6 | Israel | 1995–1999 | 41 | yes | 30% | 24% | >45 | |

| Simchen7 | Israel | 1999–2004 | 123 | no | 28% | 9.8% | 21% | >45 |

| Callaway8 | Australia | 1992–2001 | 76 | no | 13% | 8% | >45 | |

| Yogev9 | Israel | 2000–2008 | 177 | no | 16% | 11% | 17% | >45 |

| Glasser10 | Israel | 2004–2008 | 131 | yes | 42% | 18% | 43% | >45 |

| Carolan11 | Australia | 2005–2006 | 217 | no | 4.6% | 9.7% | >45 | |

| Jacquemyn12 | Belgium | 2005–2010 | 421 | no | 11% | 7.6% | >45 | |

| Le Ray13 | France | 2008–2010 | 380 | yes | 8.7% | 6.1% | >43 | |

| Kort15 | USA | 101 | yes | 23% | 3% | >50 |

Table 2. Mode of delivery and obstetric complications in VAMA.

| Lead author | Instrumental delivery | LSCS delivery | PPH |

| Jacobsson17 | 4.7% | 30% | |

| Paulsen5 | 6% | 78% | |

| Sauer18 | 65% | ||

| Sheffer-Mamouni6 | 72% | ||

| Simchen7 | 75% | ||

| Callaway8 | 3.9% | 49% | |

| Yogev9 | 3.4% | 79% | |

| Glasser10 | 94% | ||

| Carolan11 | 55% | 9.7% | |

| Jacquemyn12 | 8.3% | 43% | |

| Le Ray13 | 45% | 7.4% |

Table 3. Perinatal outcomes in VAMA.

| Lead author | Preterm <37/40 | Preterm <37/40 | SGA | Perinatal mort. |

| Jacobsson17 | 9.4% | 3.5% | 5% | 1.4% |

| Sheffer-Mamouni6 | 15% | 7.6% | ||

| Simchen7 | 14% | 34% | ||

| Callaway8 | 10% | 2.6% | ||

| Yogev9 | 22% | 6% | 11% | |

| Glasser10 | 34% | 29% | ||

| Carolan11 | 17% | 11% | 1.3% | |

| Jacquemyn12 | 17% | 9.2% | 3.6% | |

| Le Ray13 | 19% | 7.9% | 28% |

Counselling women prior to treatment

It is recommended that women have pre-pregnancy review and counselling by a clinician experienced in caring for women with potentially high-risk pregnancy.1,20,22 This clinician may be a physician with obstetric medicine training or an obstetrician with either maternal-fetal medicine training or with substantial experience caring for high-risk pregnancy. It is not known whether medical review of older women considering pregnancy offers any benefit with regards to predicting adverse outcome or offer any preventative role in improving pregnancy outcomes.

It would seem reasonable for all women considering pregnancy beyond the age of 45 years, or at a younger age if they have pre-existing medical issues, to have the opportunity to have pre-pregnancy advice from an independent expert medical practitioner. This review should include:

- a full personal and family medical history;

- a review of regular medications and the consequences of these for pregnancy;

- a medical examination including weight, height, cardiovascular examination and general examination;

- up-to-date recommended screening tests including cervical smear testing, breast screening and bowel and skin cancer screening for those at higher risk;

- standard blood tests including renal, liver and thyroid function, antenatal bloods and diabetes screening (either an HbA1c or a glucose tolerance test in higher risk patients);

- standard blood tests including renal, liver and thyroid function, antenatal bloods and diabetes screening (either an HbA1c or a glucose tolerance test in higher risk patients);

- a discussion regarding the potential risks of pregnancy for themselves and for potential offspring, including the possibility of maternal hospitalisation, preterm delivery and operative delivery;

- advice to avoid fertility treatments that substantially increase the risk of multiple pregnancy; and

- advice regarding optimal prenatal and pregnancy care,including exercise, diet, weight loss, prenatal vitamin intake, specialist obstetrician oversight and a discussion of the potential modest benefit of low dose aspirin and calcium supplementation. If a woman is contemplating donor oocyte therapy, then a delay in treatment to optimise her own health is likely to be beneficial.

This review should be additional to the counselling routinely provided by fertility treatment providers and be provided by a clinician with no financial interest in the woman proceeding with fertility treatment.

Societal and ethical considerations

Increased maternal and neonatal complications secondary to VAMA pregnancies will result in increased financial and resource cost to the public health system in both the short term and potentially the long term for babies with complications of prematurity. It is unlikely that this has been taken into account in future planning for funding and planning of antenatal and neonatal services.

VAMA is often accompanied by very advanced paternal age (VAPA). The consequences for offspring of VAPA are not well defined, but may include an increased risk of new gene mutations, fetal congenital malformations, schizophrenia and autistic spectrum disorder.21

Ethical issues with assisting women to achieve VAMA pregnancies are considerable.22 It is ethically warranted to decline to provide treatment to women who have underlying medical conditions that may further increase maternal or neonatal risks. Fertility treatment providers must take responsibility for ensuring an appropriate and ethically defendable decision is made. There is a lack of data regarding any potential long-term adverse medical and psychological outcomes for oocyte donors, which could be rectified by longitudinal follow up by fertility service providers.23

There is no evidence of social or psychological adverse effects for children with older parents, but the risk of age-related parental illness or death occurring earlier in a child’s life is likely be increased. The health of both parents should be taken into consideration when determining this potential risk.

Conclusion

Advances in reproductive technology, particularly donor oocyte and donor embryo programs, have opened a door, allowing increasing numbers of women to undertake pregnancies at VAMA. Providers of these treatments have a professional, ethical and moral obligation to ensure that prospective parents understand the potential risks of these pregnancies and have access to independently provided medical assessment and counselling. The long-term implications for children born to mothers of VAMA and the consequences for the health system remain undetermined.

References

- RANZCOG position paper on Assisted Reproductive Treatment in women of advanced maternal age (https://www.ranzcog.edu.au/doc/assisted reproductive-treatment-for-women-of-advanced-maternalage.

html). - Paulson RJ. Does the age of the recipient influence the probability

of pregnancy among recipients of oocyte donation? Fertil Steril

2013;101:1248. - CDC National ART success rates 2012.

- Pregnancy outcomes decline in recipients over age 44: an analysis of

27,959 fresh donor oocyte in vitro fertilisation cycles from the Society

for Assisted Reproductive Technology. Fertil Steril 2014;101:1331-36. - Paulson RJ et al. Pregnancy in the sixth decade of life. Obstetric outcomes in women of advanced reproductive age. JAMA 2002;288:2320-3.

- Sheffer-Mimouni et al. Factors influencing the obstetric and perinatal outcome after oocyte donation. Hum Repro 2002; 17:2636-2640.

- Simchen et al. Pregnancy outcome after 50. Obstet Gynaecol 2006; 108:1084-

- Callaway et al. Pregnancy outcomes in women of very advanced maternal age. Aust NZ J Obstet Gynaecol 2005; 45:12-16.

- Yogev et al. Pregnancy outcome at extremely advanced maternal age. AJOG 2010; 203: 558.e1-7.

- Glasser etal. Primiparity at very advanced maternal age (>45 years). Fertil Steril 2011; 95: 2548-51.

- Carolan et al. Very advanced maternal age and morbidity in Victoria, Australia: a population based study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 2013; 13:80.

- Jacquemyn et al. Pregnancy at late premenopausal age: Outcomes of pregnancies at 45 years and older in Flanders, Belgium. J Obstet Gynaecol 2014; 34: 479-481.

- Le Ray et al. Association between oocyte donation and maternal and perinatal outcomes in women aged 43 years or older. Hum Repro 2012; 27: 896-901.

- Schutte et al. Maternal death after oocyte donation at high maternal age: case report. Repro Health 2008; 5:12.

- Kort et al. Pregnancy after age 50. Defining risks for mother and child. Amer J Perinatol 2012; 29(04): 245-250.

- Gilbert et al. Childbearing beyond age 40: Pregnancy outcome in 24,032 cases. Obstet Gynaecol 1999; 93: 9-14.

- Jacobsson et al. Advanced maternal age and adverse perinatal outcome. Obstet Gynecol 2004;104:727-33.

- Sauer et al. Oocyte donation to women of advanced reproductive age: pregnancy results and obstetrical outcomes in patients 45 years and older. Hum Repro 1996; 11: 2540-43.

- Soderstrom-Anttila. Pregnancy and child outcome after oocyte donation. Hum Repro Update 2001; 7: 28-32.

- Canadian Institute for Health Information. In due time: why maternal age matters. www.cihi.ca .

- SOGC Committee Opinion. Delayed child-bearing. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2012;34(1):80-93.

- Ethics Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Oocyte or embryo donation to women of advanced age: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril 2013;100:337-40.

- Woodriff et al. Advocating for longitudinal follow-up of the health and welfare of egg donors. Fertil Steril 2014;102:662-666.

Leave a Reply