Establishing an outpatient hysteroscopy service at the Royal Hobart Hospital has been a success story.

Hysteroscopic inspection and biopsy of the uterine cavity is important in the work up towards diagnosis of intrauterine abnormalities. Modern diagnostic hysteroscopy began in the 1970s, when the uterine cavity was seen clearly with the use of distension media.1 Hysteroscopy can be performed in the outpatient setting or under general anaesthesia in the operating theatre. Outpatient hysteroscopy is a service gaining in popularity and acceptability from both a clinician and patient perspective.2 This article outlines the steps the Royal Hobart Hospital (RHH) took to set up and offer a truly ambulatory service.

Background

The RHH is Australia’s second-oldest hospital. It is Tasmania’s largest hospital and it’s major referral centre, serving a population of around 240 000 in the Southern region.3 The gynaecology service receives just over 200 new referrals per month. Women are seen across six outpatient clinics by staff specialists and registrars.

Hysteroscopy was offered solely as an inpatient day case theatre procedure under general anaesthetic until 2014. In 2013, there were on average 22 hysteroscopies (range 15–25) performed each month. As gynaecology had one of the shortest waiting lists, and with pressure on other specialties to address their waiting lists, gynaecological operating lists were under constant threat of being reduced. There was an impetus to look at other ways of addressing the problem and freeing up capacity. It became obvious that by a process of clinical redesign, hysteroscopy could be offered on an outpatient basis, improving the patient journey and experience.

Clinical redesign and innovation

Clinical services redesign is defined as the application of robust analysis of the patient journey to assist in achieving the desired outcomes.4 By moving hysteroscopies to the outpatient setting, capacity in the inpatient lists could be freed to allow for more major gynaecological operations to be performed. This also reduced the waiting times and improved access for investigation of women with abnormal uterine bleeding, especially postmenopausal bleeding. A case was made to the RHH Board under the Innovation Funds bid.

The benefits of the clinical redesign for patients and the success of such units in overseas centres were demonstrated. On this basis, the department received the necessary funding to set up the service.

Stakeholders were invited to participate in a consultation process and a change management program was instituted. The working group consisted of key medical and nursing staff, the business manager of the department, GP liaison officers, the operating theatre manager, infection control personnel and nurse educators. Guidelines from Australian and overseas centres were reviewed to help formulate our pathways. Although the initial outlay for establishing a new procedural clinic may be significant, the day-to-day running costs of this service will ensure long-term cost savings.5 It was estimated the revenue generated per case of outpatient hysteroscopy under the current Medicare payment scheme would be cost neutral, but improved throughput for other inpatient gynaecological cases would be more efficient and could also increase net income.

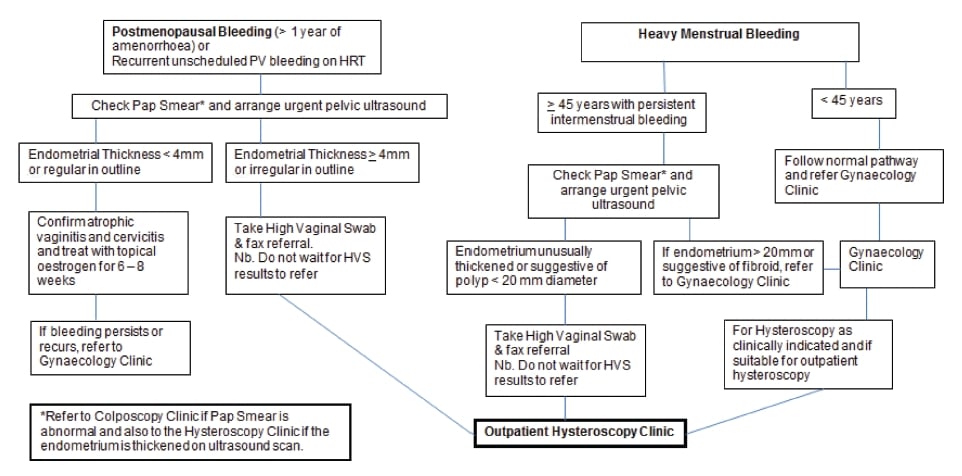

Figure 1. RHH pathways for referral to the outpatient hysteroscopy service.

Figure 2. GyneCare Alphascopes sheath and hysteroscope.

The outpatient hysteroscopy procedure uses different hysteroscopes to those used in theatre. After extensive testing of several excellent makes of outpatient hysteroscopes, the GyneCare® Alphascopes (see Figure 2), the Aquilex® fluid management system and the Karl Storz Aida® image-capture systems were chosen.

Clinical pathway and current program

A patient will require a hysteroscopy for investigation of abnormal uterine bleeding and/or endometrial abnormalities. Our pathway is shown in Figure 1. A thorough work up for other causes of abnormal bleeding should be completed prior to hysteroscopy. Pap smears should be up to date and colposcopy done first, if necessary. Prior to hysteroscopy, a high vaginal swab is taken and infections (including thrush or bacterial vaginosis) treated. Pelvic ultrasound will help determine the necessity for hysteroscopy. This preparation can be performed by the GP so the service becomes a ‘one-stop, see-and-treat’ service.6

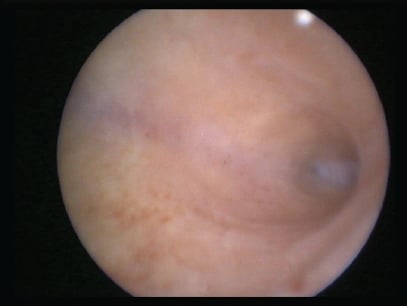

Patients are advised not to fast and to take simple analgesics around one hour before their appointment. The procedure involves vaginoscopy to guide the hysteroscope into the cervical canal.7 The vaginoscopy or ‘no touch’ technique is atraumatic and further reduces patient pain.8 This avoids the use of a speculum and tenaculum and involves saline distension of the vagina to find the cervix. It provides more manoeuvrability in patients where the uterus may be acutely flexed, in patients with a raised body mass index and in those who may not tolerate a speculum examination.6 In most cases this has been successful.9 Hydro-dilatation of the cervical canal is performed using normal saline, which has been shown to be more beneficial in terms of patient comfort, cost effectiveness and decreased post-procedure bleeding.10 Good views of the cervix and endometrial cavity are obtained (see Figures 3–7). Biopsies or minor surgical procedures such as removal of polyps or small submucous fibroids with grasping forceps or the Twizzle® bipolar diathermy electrodes (see Figure 8) can be performed through the expandable operating sheath. The collapsible plastic operating channel can be used without removing the hysteroscope or dilating the cervix further. In our current clinical environment, if more extensive intrauterine procedures need to be performed, hysteroscopy under general anaesthetic will be arranged. Hysteroscopy under general anaesthesia is still indicated if the outpatient setting has failed owing to patient discomfort or in cases of patient preference, virginal women and where a patient’s cardiac conditions means normal responses to vaso-vagal reactions are blunted.6 There is also a weight limitation of 170kg for our examination couches.

From top, Figures 3–6. View of the cervix at vaginoscopy; endocervical canal and internal os; endometrial cavity; right tubal ostium.

Figure 7. Left tubal ostium. Clinical images reproduced with permission from the individual patients.

Up and running

The RHH outpatient hysteroscopy service saw its first patient on 31 January 2014. There are currently two consultant-led clinics per week with a dedicated gynaecology nurse and a training registrar rostered. The clinic sessions run at a maximum of five patients each allocated 45 minutes. After the procedure, there is a short period of observation. There is also resuscitation equipment available. A private area for the patient to change is also provided.

Clinical problem shooting

Pain

Studies show that although patients may be anxious initially, most patients will tolerate outpatient hysteroscopy.2,5,11-12 In our clinic, simple analgesia is advised prior to the procedure. The diameter of the hysteroscope we use is 1.8mm and with the outer sheath, it becomes 3.5mm. This means that in most cases, there is no need to manually dilate the cervix. The presence of a nurse to talk to the patient or reassure her (‘vocal anaesthesia’) is important.

Vasovagal reaction

So far, only one patient required a longer period of observation post-procedure for a mild vasovagal response. This occurred several minutes after the procedure had been completed and resolved spontaneously. She had forgotten to take her pre-procedure analgesic. Vasovagal response to outpatient hysteroscopy is rare, but has been described.13 Techniques to reduce anxiety, mentally prepare the patient and adequate analgesia are helpful.13 Nevertheless, adequate resuscitation equipment and clinical vigilance are crucial.

Failed procedure

A failed outpatient hysteroscopy procedure is when the cervical canal cannot be entered or when an adequate view of the uterine cavity cannot be obtained. The use of the vaginoscopy technique, normal saline as the distension medium and use of the thinner hysteroscope are factors that improve success.14 In the current literature, over 95 per cent of cases are successful.8,13-15 Patient anxiety and emotional preparedness also influence success.16

Figure 8. Twizzle bipolar diathermy electrode. Reproduced with permission from Johnson & Johnson Pty. Ltd. Australia.

Patient feedback

Obtaining patient feedback has allowed us to improve our services and audit its acceptability. Some of the comments so far include:

- No bleeding at all, the discomfort was like period pain, and would go through it again. It was really good not to have an anaesthetic. Not as bad as having a pap smear. I had no soreness or pain after the procedure.

- It was good, no anaesthetic and no grogginess. The procedure was not uncomfortable; putting the Mirena in was the worst part. It is an excellent service.

- Back at work, had slight spotting after the procedure. During the procedure hardly any discomfort, things were explained really well and [the nurse] did an excellent job of distracting me. A bit concerning having so many people in the room.

The majority of patients have felt the discomfort was minimal and offering hysteroscopy in an outpatient setting results in faster recovery and less time away from work and home.

Future aims

The outpatient hysteroscopy clinic at RHH has been successful in providing a fast-tracked service for women with abnormal uterine bleeding. Nursing and medical staff have seen the benefits and acceptability of the procedure. Clinical expertise can be built upon with more training registrars becoming competent in this procedure. Possibilities for the future include operative procedures such as resection of fibroids, adhesions and septae, hysteroscopic tubal occlusion, infertility investigation and endometrial ablation.6 We believe the outpatient hysteroscopy service is beneficial from an economic, evidence-based and patient perspective.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge all stakeholders involved in setting up the RHH outpatient hysteroscopy service.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

References

- Edstrom K, Fernstrom I. The diagnostic possibilities of a modified hysteroscopic technique. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 1970;49:327-30.

- Kremer C, Duffy S, Moroney M. Patient satisfaction with outpatient hysteroscopy versus day case hysteroscopy: Randomized controlled trial. BMJ 2000; 320:279-282.

- Royal Hobart Hospital Website www.dhhs.tas.gov.au/hospital/royal-hobart-hospital Department of Health and Human Services.

- PriceWaterhouseCoopers Redesigning Healthcare Summit. 2007.

- Symonds IM. Establishing an outpatient hysteroscopy service. Current Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1999;9:158-162.

- Cooper NAM, Clark TJ. Ambulatory hysteroscopy. The Obstetrician & Gynaecologist. 2013;15:159-66.

- Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Best Practice in Outpatient Hysteroscopy. London: RCOG; 2011.

- Cicinelli E, Parisi C, Galantino P, Pinto V, Barba B, Schonauer S. Reliability, feasibility and safety of minihysteroscopy with a vaginoscopic approach: experience with 6,000 cases. Fertil Steril 2003;80:199-202.

- Cooper N, Smith P, Khan K, Clark T. Vaginoscopic approach to outpatient hysteroscopy: a systematic review of the effect on pain. BJOG 2010;117:532-539.

- Wieser F, Tempfer C, Kurz C, Nagele F. Hysteroscopy in 2001: a comprehensive review. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2001;80:773-783.

- Tahir MM, Bigrigg MA, Browning JJ et al. A randomized controlled trial comparing transvaginal ultrasound, outpatient hysteroscopy and endometrial biopsy with inpatient hysteroscopy and curettage. BJOG 1999; 106:1259-1264.

- Lau WC, Ho RYF, Tsang MK et al. Patient’s acceptance of outpatient hysteroscopy. Gynecol Obstet Invest 1999; 47:191-193.

- Bellingham RF. Outpatient hysteroscopy – Problems. ANZJOG. 1997;37(2):202-205.

- Di Spiezio Sardo A, Taylor A, Tsirkas P, Mastrogamvrakis G, Sharma M, Magos A. Hysteroscopy: a technique for all? Analysis of 5000 outpatient hysteroscopies. Fertil Steril 2008;89(2):438-443.

- Gulumser C, Narvekar N, Pathak M, Palmer E, Parker S, Saridogan E. See-and-treat outpatient hysteroscopy: an analysis of 1109 examinations. Reproductive Biomedicine Online. 2010;20(3):423-429.

- Gupta JK, Clark TJ, More S, et al. Patient anxiety and experiences associated with an outpatient ‘one-stop’ ‘see and treat’ hysteroscopy clinic. Surg. Endosc. 2004;18:1099-1104.

Leave a Reply