There are a plethora of surgical procedures available for pelvic organ prolapse (POP) repair. Perhaps the most important factor is to consider the apical compartment when performing any repair, as failure to address this will lead to an increase in recurrence risk. A customised approach to POP surgery is essential.

POP is an increasing problem as the western population ages. In the US, about 200 000 prolapse surgeries are performed annually, with 11–19 per cent of women requiring POP or continence surgery by the age of 80.¹ POP can be found in up to 50 per cent of parous women on vaginal examination, however, if symptom free no intervention is required. For women with prolapse symptoms – such as a bulge, dragging, back pain, voiding, defaecatory or sexual dysfunction – conservative or surgical options are available. A discussion of conservative options is not within the remit of this short article, but is generally most suited to women who have not completed their family, are medically unfit or do not wish to undergo surgery.

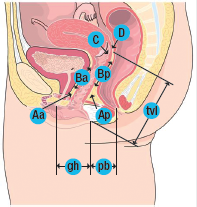

POP is divided into compartments: the anterior compartment (cystocele or urethrocele), apical compartment (vault or uterine prolapse) and posterior compartment (rectocoele or enterocoele). In reality, many women have multi-compartment prolapse. Use of a POP quantification (POP-Q) exam (see Box 1) will help to delineate the extent of prolapse in each compartment so a surgical plan can be created.

he options for surgical repair are wide and choice will depend on a number of factors, including the stage of prolapse, compartments involved, the patient’s age, lifestyle, sexual activity, BMI, comorbidities and previous history of POP surgery. The operating surgeon should have the ability to tackle a prolapse repair using a variety of surgical approaches so that surgery can be customised for the individual patient. The aim of prolapse surgery should be to: restore vaginal anatomy and improve or maintain bladder, bowel and sexual function. For elderly women, obliterative surgery may be the most appropriate surgical option.

Apical compartment prolapse

Abdominal sacrocolpopexy (ASC), sacrospinous or ileo coccygeus suspension fixation and uterosacral suspension are the most commonly performed apical suspension procedures. Open ASC is traditionally performed through a Pfannenstiel incision, although increasingly via a laparoscopic or robotic approach. To date, robotic procedures do not confer an advantage over laparoscopic procedures, but do incur a longer operating time and higher cost. Open procedures are associated with a longer hospital stay and more postoperative pain, but no difference in patient satisfaction or surgical outcomes.

Box 1. POP-Q exam

The POP-Q exam12 is used to quantify, describe, and stage pelvic support. There are six points measured at the vagina with respect to the hymen. Points above the hymen are negative numbers; points below the hymen are positive numbers. All measurements except tvl are measured at maximum Valsalva.

| Point | Description | Range of values |

|---|---|---|

| Aa | Anterior vaginal wall 3 cm proximal to the hymen | -3 cm to +3 cm |

| Ba | Most distal position of the remaining upper anterior vaginal wall | -3 cm to +tvl |

| C | Most distal edge of cervix or vaginal cuff scar | |

| D | Posterior fornix (N/A if post-hysterectomy) | |

| Ap | Posterior vaginal wall 3 cm proximal to the hymen | -3 cm to +3 cm |

| Bp | Most distal position of the remaining upper posterior vaginal wall | -3 cm to + tv |

Genital hiatus (gh) – Measured from middle of external urethral meatus to posterior midline hymen. Perineal body (pb)– Measured from posterior margin of gh to middle of anal opening. Total vaginal length (tvl) – Depth of vagina when point D or C is reduced to normal position.

POP-Q staging criteria

| Stage 0 | Anterior vaginal wall 3 cm proximal to the hymen |

| Stage l | Stage 0 criteria not met and leading edge < -1 cm |

| Stage ll | Leading edge ≥ -1 cm but ≤ +1 cm |

| Stage lll | Leading edge > +1 cm but < + (tvl – 2) cm |

| Stage lV | Leading edge ≥ + (tvl – 2) cm |

Success rates after ASC range from 76–100 per cent, with a four per cent reoperation rate for prolapse.² The incidence of mesh extrusion with ASC using polypropylene mesh is low, at around 0.5 per cent, increasing if a hysterectomy is performed concurrently. Recent studies show performing a subtotal hysterectomy will minimise the risk of mesh extrusion. In the recent FDA statement, mesh used in ASC was retained for use as a Class 2 product under the 510K ruling and has not been associated with the incidence of complications associated with vaginal mesh.

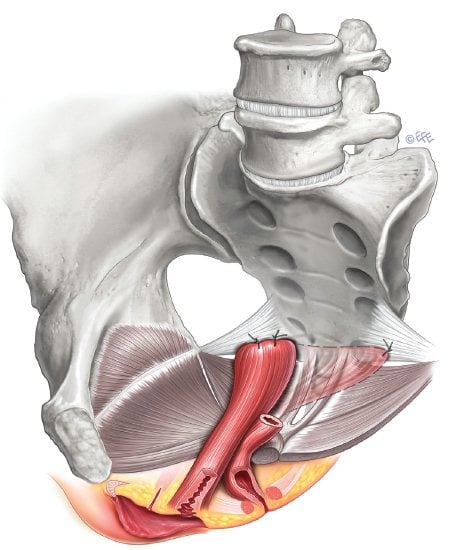

Sacrospinous fixation

Sacrospinous fixation (SSFxn) provides excellent vaginal vault support (see Figure 1), with recurrence rates ranging from 2–19 per cent and objective cure rates of 67–97 per cent.³ Traditionally, sutures are placed in the right suture suspension lift. Some advocate bilateral SSFxn; however, this approach requires an adequate vaginal vault width and length and, to date, hasn’t been associated with improved outcomes. Sacrospinous hysteropexy is gaining in popularity, with a reported reduction in surgical time, risk of complications and blood loss, but a possible increase in recurrence rates, and may best be reserved for older women with small atrophic uteri and no cervical hypertrophy until more data are available.

Braided sutures, such as Ethibond, are associated with an increased risk of suture extrusion, infection and granulation formation. Monofilament sutures, such as prolene or PDS, are more suitable. The incidence of buttock pain with SSFxn is around ten per cent. This is usually short lasting and careful placement of sutures 2cm medial to the ischial spine and the use of a suture carrier such as the I stitch or Capio will reduce the risk of damage to the sciatic nerves sitting posterior to the ligament.

The incidence of haemorrhage with SSFxn is low, at 1.8 per cent, despite popular belief most haemorrhage during sacrospinous fixation is a result of damage to the inferior gluteal artery, which runs behind the sacrospinous ligament, rather than damage to the pudendal artery. This is best treated with packing and interventional radiological techniques. The recent Cochrane review by Maher et al concluded that ASC, when compared to SSFxn, was associated with a lower rate of vaginal vault prolapse and reduced dyspareunia rates, but a higher cost and longer operating and recovery time than vaginal surgery. SSFxn results in a posterior angulation of the vagina and this has been associated with an increased risk of cystocele formation.

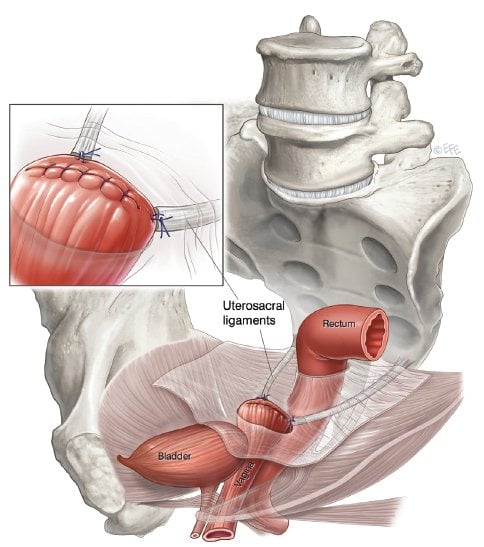

Uterosacral ligament suspension

Uterosacral ligament suspension (USL) suspension provides a more anatomical axis to the vagina than SSFxn (see Figure 2), but owing to the attenuation of the ligaments would be less suitable for women with advanced stages of prolapse. Success rates are quoted at 81–98 per cent.4 Many different approaches are described all with the aim of placing several permanent or absorbable sutures from the USL to the vaginal vault, thus resulting in vault elevation and reduction of enterocoele. Care needs to be taken in suture placement to avoid ureteric entrapment or kinking and performing a cystocopy at the time of surgery is essential. Sutures placed too deeply may result in pain or numbness along the S2, S3 dermatomes.

There is, as yet, no RCT comparing SSFxn with USL suspension for apical support, but a trial is underway.

Anterior vaginal wall prolapse repair

Traditional native tissue repair involves the plication of the pubocervical fascia using an absorbable suture. Of anterior compartment prolapses, 50–60 per cent have an additional element of apical prolapse, which will need to be addressed to get a good anatomical result. Failure to do so may, in part, account for the recurrence rates of up to 40 per cent reported in the literature.5 Attaching the pubocervical fascia to the vault or cervix with a suture will also aid support. Paravaginal repair techniques have largely fallen out of favour owing to a lack of efficacy.6 In 2010, in the US, a quarter of prolapse cases were managed with a mesh implant. In 2008 and 2011, the FDA issued statements regarding the safety and efficacy of vaginal mesh implants, this was followed by a frenzy of lawsuits and an inevitable decline in mesh use.7 Data from radomised controlled trials, summarised in a Cochrane Review in 20138 and the FDA report, found that use of surgical mesh for anterior compartment repair has potentially higher anatomical success rates than repair without mesh, but results in similar subjective success rates and a higher complication rate than traditional vaginal surgery. Judicious use of vaginal mesh by experienced surgeons is therefore recommended with stringent patient counselling prior to implantation. The IUGA round table discussion document9 is a useful source of guidance on which patients may benefit from vaginal mesh.

Figure 1. Sacrospinous ligament fixation. Image courtesy IUGA, copyright Levente Efe.

Figure 2. Uterosacral ligament suspension. Image courtesy IUGA, copyright Levente Efe.

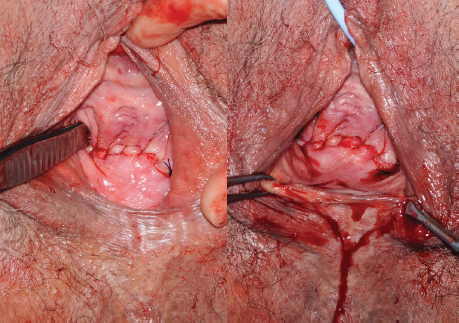

Figure 3. LeFort colpocleisis, on the right completion of Le Fort colpocleisis with a perineorrhaphy.

Stress urinary incontinence

Detailed discussion of stress urinary incontinence (SUI) is not within the remit of this article; however, de novo SUI needs to be considered in all women with advanced POP. Urodynamics with a pessary in situ can be performed before surgery and a continence procedure performed at the time of POP repair. Another approach is to warn the patient of the risk of de novo SUI (about eight per cent) and perform a two-stage procedure if necessary.

Posterior compartment repair

The posterior compartment is supported by the level 1 support systems (uterosacral and cardinal ligaments), level 2 supports(with the endopelvic fascia) and level 3 supports (the perineal body). The puborectalis portion of the levator ani muscles is particularly important in maintaining the rectal angle and also the genital hiatus. Assessment of these supports prior to surgery is important so a suitable repair can be performed. Many women suffer from symptoms of obstructed defaecation. This may be owing to a prolapse, but also to intussusception or rectal prolapse and assessment with a defaecating proctogram or MRI before surgery may be indicated, particularly if symptoms do not match examination findings.

Native tissue repair is customarily performed as a site-specific repair or a traditional rectocoele repair. Anatomical cure rates are very similar with both techniques at 80–100 per cent. The addition of a perineorrhaphy will reduce vaginal calibre and add support, but care should be taken not to narrow the vagina excessively. Levatorplasty does narrow the vagina, however, it may also result in dyspareunia and pelvic pain and should be performed with caution, if at all, in sexually active women. Use of reconstructive materials (synthetic or biological) to augment the repair of posterior vaginal wall prolapse is not supported by current evidence8 and should only be considered in exceptional cases.

Obliterative procedures

Colpocleisis is an extremely effective procedure for women with advanced POP, with success rates in excess of 90 per cent.10 The procedure is quick, simple and can be performed under local anaesthetic if required. LeFort or partial colpocleisis (see Figure 3) involves removal of a strip of vaginal mucosa anteriorly and posteriorly and should be performed for women with an intact uterus. Total colpocleisis involves the removal of all vaginal mucosa. In both cases, 3–4cm of vaginal mucosa should be retained distally so the urethra is not distorted. The incidence of SUI following colpocleisis is up to 30 per cent, a mid-urethral sling may therefore be of benefit at the time of surgery.11 Colpocleisis precludes future penetrative sexual activity, so careful counselling is required prior to surgery. Women should be screened before surgery for endometrial thickness and have a normal cervical screening history, as the cervix will no longer be accessible following surgery.

For illustrated patient information brochures on POP surgery and more, visit the International Urogynecological Association website at: www.iuga.org, they are free to download.

References

- Smith FJ, Holman CD, Moorin RE, Tsokos N. Lifetime risk of undergoing surgery for pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2010; 116:1096.

- Nygaard IE, McCreery R, Brubaker L, Connolly A, Cundiff G, Weber AM, Zyczynski H, Pelvic Floor Disorders Network Abdominal sacrocolpopexy: a comprehensive review.Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104(4):805.

- Beer M, Kuhn A. Surgical techniques for vault prolapse: a review of the literature. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2005; 119:144.

- Kenton K et al Pelvic organ prolapse in women: Surgical repair of apical prolapse (uterine or vaginal vault prolapse) In: UpToDate, Brubaker L (Ed) UpToDate, Waltham, MA, 2013.

- Delancey JO. Surgery for cystocele III: do all cystoceles involve apical descent? : Observations on cause and effect. Int Urogynecol J. 2012; 23:665.

- Sangeeta et al Pelvic organ prolapse in women: Surgical repair of anterior vaginal wall prolapse In: UpToDate, Brubaker L (Ed) UpToDate, Waltham, MA, 2013.

- Urogynecologic Surgical Mesh: Update on the Safety and Effectiveness of Transvaginal Placement for Pelvic Organ Prolapse July 2011 www.fda.gov/downloads/MedicalDevices/Safety/AlertsandNotices/ UCM262760.pdf .

- Maher C, Feiner B, Baessler K, et al. Surgical management of pelvic organ prolapse in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013; CD004014.

- IUGA Grafts Round Table. Int Urogynecol J. 2012 Apr; 23 Suppl 1:S7-14.

- Zebede S, Smith AL, Plowright LN, et al. Obliterative LeFort colpocleisis in a large group of elderly women. Obstet Gynecol. 2013; 121:27

- FitzGerald MP, Brubaker L. Colpocleisis and urinary incontinence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003; 189:1241.

- Bump RC, Mattiasson A, Bo K, et al. The standardization of terminology of female pelvic organ prolapse and pelvic floor dysfunction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:13.

Leave a Reply