Obstetric anal sphincter injuries are a significant risk to the maintenance of anal continence in both the short and long term. This risk can be significantly reduced by identifying the injury, reconstructing the sphincter complex and optimising recovery.

This article will outline the process of recognition, repair and postoperative care to minimise the adverse effects on the woman’s quality of life and future pregnancies of obstetric anal sphincter injuries (OASIS).

Recognition and diagnosis

‘No finger, no diagnosis!’ is the decree of Mr Abdul Sultan, consultant obstetrician and gynaecologist with a special interest in urogynaecology at Croydon University Hospital and honorary Reader at St George’s, University of London. The UK NICE Intrapartum Care Guideline states: ‘If any evidence of perineal trauma is identified on initial visual assessment following vaginal delivery, further systematic assessment must include a rectal examination to exclude OASIS.’1 Without a digital rectal examination, OASIS cannot be excluded. Even those appearing to have an ‘intact perineum’ may have vaginal tears and these must be excluded after all vaginal deliveries.

Before beginning the assessment, explain the reason for the examination, obtain consent and provide adequate analgesia. In those requiring further examination, the recommended rectovaginal technique is to: position the patient into lithotomy to improve wound visualisation; and insert index finger into the anal canal and thumb into the vagina. Aim to ‘pill-roll’ the sphincter between the thumb and finger, starting from the midline then moving laterally in both directions to ensure the sphincter is complete along both its circumference and length. Identify the following:

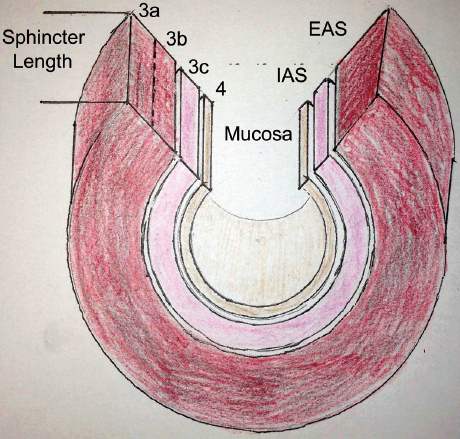

- External anal sphincter (EAS) – similar appearance to raw beef. The ishioanal fat superficial and lateral to the EAS can be useful in differentiating the EAS from the transverse perineal muscles. Also, by pulling on the ends of the EAS, the posterior aspect the anus will lift.

- Internal anal sphincter (IAS) – similar appearance to raw chicken, found deep to the external sphincter, remembering that it does not extend to the subcutaneous portion of the EAS.

- Rectal mucosa, also excluding any buttonhole tears.

Figure 1. Anal sphincter complex and OASIS classification.

All perineal injuries should be classified according to the RCOG OASIS Classification2 (see Figure 1). Buttonhole tears are not included in this classification and should be documented separately. If there is uncertainty about the severity of tear it should be classified at the higher grade to ensure appropriate vigilance is given to the repair and follow-up.

Preparation

Do I really need to repair this in theatre?

The default answer to this question is yes. However, if the same conditions and results can be achieved on the labour ward, this may be acceptable in some circumstances, for incomplete external sphincter disruption only. The requirements, whether the repair is performed in theatre or in labour ward, are the same:

- clean conditions;

- anaesthesia – regional or general anaesthesia to allow sphincter relaxation;

- adequate wound exposure:

– good lighting

– adequate positioning in lithotomy

– skilled assistance

– good haemostasis; and - equipment: additional clamps for grasping the sphincter (such as Allis clamps) and sutures (such as 4x artery clamps). A self-retraining retractor (for example, Weitlaner) can be invaluable.

In addition to these requirements, a single dose of a second-generation cephalosporin (such as Cefoxitin) administered intraoperatively significantly reduces perineal wound infections from 24.2 per cent to 8.2 per cent (p <0.05).3 Clindamycin or lincomycin are suitable alternatives in those allergic to cephalosporins.

Sometimes there are inevitable delays in gaining access to theatre. Nordemstam and colleagues reported equivalent functional outcomes between those women whose injuries are repaired immediately compared to those waiting up to 12 hours.4 However, tissues tend to become more oedematous and friable with time, making the repair more challenging. As well, other practical issues such as ongoing bleeding need to be considered. All things considered, OASIS repairs are a priority and should be dealt with as soon as possible.

Reconstruction

- Achieve adequate haemostasis to provide good wound exposure.

- Begin repair with the deepest injured structure.

Rectal mucosa

Re-appose the rectal mucosa with a standard 3-0 braided or monofilament synthetic suture in an interrupted or continuous fashion, taking care to incorporate the apical angle of the tear. When using synthetic sutures, the knots can be tied either in the lumen or extraluminally, unlike catgut which should be tied within the lumen.

IAS

The IAS should be repaired separately to the EAS to ensure it is reconstructed anatomically. It provides 80 per cent of resting anal pressure and when not intact may cause urgency symptoms, as well as passive faecal and flatal incontinence. A 3-0 delayed absorbable monofilament suture using a horizontal mattress technique 0.5cm from the torn edge with 1cm bites distributes the tension across length of the wound (see Figure 2).

EAS

Whether performing an end-to-end or an overlapping EAS repair, the aim is to re-appose the full depth and length of the EAS to maximise the functional anal length. The choice of technique is dependent on the following:

- Degree of sphincter disruption – (3a or incomplete 3b) – an end-to-end approach is used. A complete overlap is not possible in these situations and it is not advised to cut the remaining intact sphincter to achieve the overlap.

- The surgeon’s confidence in dissecting the EAS to enable an adequate overlap.

- The training and experience of the surgeon.

The steps of the repair are:

- Identify and grasp the full length and depth of each end using two atraumatic forceps (for example, Allis clamps).

- For either technique, two or three sutures are usually adequate. Figure-of-eight sutures should not be used because of the risk of ischaemia.

- The sutures should be placed from the proximal aspect to the distal.

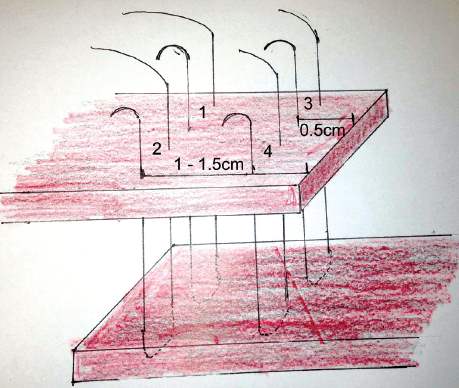

Figure 3. Overlap technique with order of sutures.

End-to-end

This is the same as described for the IAS, an important principle is tying the knots once all the sutures are placed.

Overlapping (see Figure 3 and 4)

- Ensure adequate length of the overlapping end and, if necessary, dissect the EAS laterally from the ischioanal fat to create enough length.

- The suture is inserted 1–1.5cm from the torn edge to be overlapped, from top to bottom.

- Place the suture to full thickness from top to bottom 0.5cm from the torn edge of the underlapping end. Bring the suture back through the underlapping edge from bottom to top taking a 1cm bite, again 0.5cm from the torn edge

- Place the return suture from bottom-to-top again 1–1.5cm from the edge of the overlapping torn edge, then cut and clamp the suture ends.

- Once the full length is overlapped, tie the sutures.

- Suture the loose edge of the overlapped end to the underlying

- end, with a similar technique to the other sutures. A full thickness bite of the underlapping end does not need to be taken.

- Check there is good sphincter length and bulk.

The literature demonstrates superiority of an overlapping repair in reducing faecal urgency (32 per cent versus 7.1 per cent, RR 0.12, p=0.04), and lower median modified Wexner anal incontinence score (1 versus 0, p=0.05), as well as improved anal incontinence (62.9 versus 32 per cent, p=0.02) at 12 months.5 However, this was in the hands of two experienced surgeons and this is the only study that documented separately repairing the IAS, which may have an impact on the outcomes also.

Williams and colleagues showed equivalent outcomes using a 2-0 standard braided suture (Vicryl) versus a 3-0 delayed absorbable monofilament (PDS) to reconstruct the EAS.6 However, some clinicians prefer the reassurance of the delayed absorption over the concern of suture migration and pain associated with monofilament sutures.

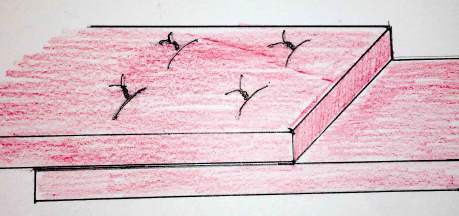

Figure 4. Completed overlap repair.

It is important to reconstruct the perineal body both to restore anatomy and overlay enough tissue to prevent suture migration and pain. The repair is completed with a rectovaginal examination to ensure good sphincter bulk and exclude any unintended anal perforation by the sphincter sutures.

Documentation

Standardised documentation of the diagnosis, repair technique and postoperative management is essential for the purposes of audit, quality improvement and follow-up. Using an electronic or paper-based structured form may increase the likelihood that all information is recorded and optimal intra-operative and post-operative management is provided.

Complication minimisation

Analgesia

At the time of repair, administration of a long-acting NSAID, for example, Diclofenac 100mg PR, has been shown to result in less pain and require less additional analgesia up to 48 hours following repair.7 Following this, strict oral paracetamol and an NSAID should be prescribed to reduce the need for opiates. Perineal cooling in the form of ice packs or gel pads for the first two days may also result in less perineal pain.8

Antibiotics

While we have good evidence for an initial dose of a cephalosporin, there is no direct evidence for ongoing antibiotics. Many clinicians prescribe a week of a broad spectrum oral antibiotic such as Amoxycillin with Clavulanic acid for five days, which seems to offer few risks and may reduce wound complications, particularly in those at higher risk of wound infection.

Catheterisation

Postoperative bladder drainage with an in-dwelling urinary catheter is recommended for at least the first 12 hours following the repair. Oedema and pain in addition to the other peripartum risk factors (for example, regional anaesthesia, instrumental delivery, high birth weight and prolonged labour), all increase the risk of postpartum urinary retention. This risk can be further minimised by performing a formal trial of void to ensure effective voiding after catheter removal.

Bowel motions, dietary measures and laxatives

The objective of any dietary measure is to prevent constipation promoting the passage soft frequent motions with minimal pain or need to strain. The most important dietary advice is to maintain a good fluid intake – at least two litres per day – especially if breastfeeding. There is no evidence demonstrating benefit of any dietary restrictions, including low residual diets.

A non-bulking osmotic laxative in the form of polyethylene glycol (PEG) should be prescribed for all OASIS patients. PEG-based laxatives have been shown to be more effective and cause less abdominal bloating and flatulence than lactulose in those with constipation.9 Bulk-forming laxatives (such as Psyllium) are not recommended as routine first-line management, since they are associated with increased anal incontinence; however, they should be considered in those developing constipation. Those who have been unable to pass a bowel motion by day three should be reviewed.

Debriefing

Prior to discharge, all patients should be debriefed about the type of injury they have had, any potential contributors, how it may affect them, prevention of complications and when to seek advice. In addition to addressing the woman’s individual situation and concerns, written information detailing potential issues, prevention and management should be provided.

Conclusion

The best opportunity we have to minimise the effects of OASIS is to recognise the primary injury providing the opportunity to optimally reconstruct the sphincter complex. With good postoperative care and support, most women will make a good recovery with minimal, if any, impact on their quality of life in the short and long term.

References

-

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Intrapartum care: care of healthy women and their babies during childbirth London: NICE, 2007. (http://guidance.nice.org.uk/CG055).

- RCOG. 2007. Management of third- and fourth-degree perineal tears following vaginal delivery (Green Top Guidelines No. 29). London: Royal College of Obstetrician and Gynecologists.

- Duggal N, Mercado C, Daniels K, Bujor A, Caughey AB, El-Sayed YY. Antibiotic prophylaxis for prevention of postpartum perineal wound complications: a randomized controlled trial. Obstetrics &

Gynecology. 2008;111(6):1268–73. - Nordenstam J, Mellgren A, Altman D, López A, Johansson C, Anzén B, Li ZZ, Zetterström J. Immediate or delayed repair of obstetric

anal sphincter tears-a randomised controlled trial. BJOG. 2008

Jun;115(7):857-65. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2008.01726.x. - Fernando RJ, Sultan AHH, Kettle C, Thakar R, Radley S. Methods

of repair for obstetric anal sphincter injury. In: The Cochrane Collaboration, Fernando RJ, editors. Cochrane Database of Systematic Review. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2006. - Williams A, Adams EJ, Tincello DG, Alfirevic Z, Walkinshaw SA, Richmond DH. How to repair an anal sphincter injury after vaginal delivery: results of a randomised controlled trial. BJOG. 2006 Feb;113(2):201–7.

- Dodd JM, Hedayati H, Pearce E, Hotham N, Crowther CA.

Rectal analgesia for the relief of perineal pain after childbirth: a randomised controlled trial of diclofenac suppositories. BJOG. 2004;111(10):1059–64. - East CE, Begg L, Henshall NE, Marchant P, Wallace K. Local cooling for relieving pain from perineal trauma sustained during childbirth

(Review). 2009 Available from: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/

doi/10.1002/14651858.CD006304.pub2/pdf/standard . - Lee-Robichaud H, Thomas K, Morgan J, Nelson RL. Lactulose versus Polyethylene Glycol for Chronic Constipation, Cochrane Databse Sys Rev 2010 Jul 7;(7) CD007570

.

Leave a Reply