Can the reproductive catastrophes of a long-dead king be explained by the presence of a minor antibody in pregnancy?

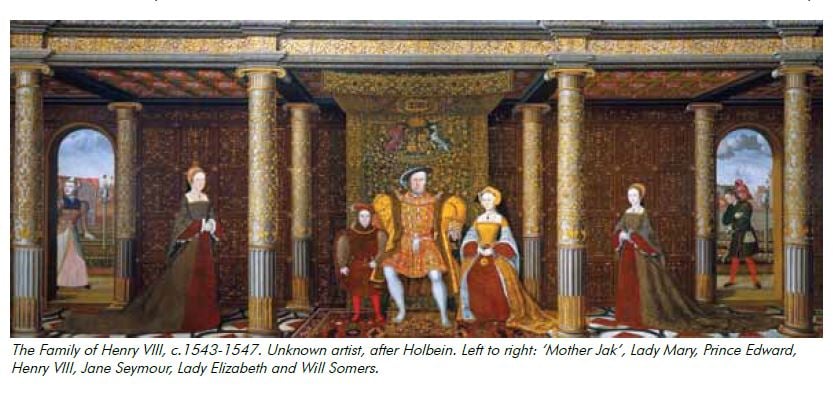

A fatal incompatibility between Henry VIII and his wives and mistresses could be the hidden reason behind the sad string of pregnancy losses experienced by the king’s partners. Although it can never be proven, the culprit for this tragic story could well be a minor antibody of pregnancy: the Kell antibody. An unconfirmed theory is that Henry VIII was unfortunate enough to be Kell positive. In association with a Kell-negative woman, he therefore had a 50 per cent chance of conceiving a Kell-positive baby. The first child by his many partners therefore tended to be healthy and unaffected by this curse, irrespective of their Kell status. However, subsequent pregnancies could be affected by this aggressive antibody if that first child had been Kell positive. The offspring who regrettably inherited their father’s Kell-positive status were at risk of attack by their mother’s antibodies, resulting in what has been described as an ‘atypical reproductive pattern’ even in an age of such high infant mortality.4 The tragic fact that only four of his 11 progeny survived infancy, of whom three were firstborn, supports this theory.4,7

Minor red blood cell antibodies, immunoglobulins, arise most commonly in response to foreign red blood cell antigens encountered. Generally, women are more prone to developing these antibodies during their reproductive years. This is usually via the multiple obstetric-related opportunities for exposure to such antigens (in other words, via a blood transfusion, feto-maternal haemorrhage or even contaminated needles). In more exceptional circumstances, the antibodies can evolve via a more passive, natural exposure to potential pathogens such as bacteria or viruses.2 For those Trainees in the midst of exams, the blunt, but helpful, expression ‘Kell kills, Duffy dies, Lewis lives’ has simplified remembering some of the more frequently encountered minor antibodies.8 In reality, minor antibodies in obstetrics are far more complicated than this simple phrase implies. These rarer antibodies are not often detected, but can still have a significant impact on a woman’s opportunity to produce a healthy infant, as perhaps indicated by the unfortunate plight of Henry VIII. The identification of these antibodies is doubly important in that donor blood for transfusion to an affected mother is required to be compatible, a possibility obviously not available in the time of the Tudor king.

In the years following the reign of Henry VIII, haemolytic disease of the newborn remained a significant contributor to the rates of fetal loss and neonatal mortality. It was not until the 1950s, that the link between poor fetal and neonatal outcome and maternal antibodies was made.1 As research has progressively shed light on antibodies in pregnancy over the last few decades, more has been able to be done to prevent the potentially catastrophic consequences of these conditions.

Fetal anaemia owing to these minor antibodies is cell-mediated and evolves in the same manner as the more commonly encountered antibodies: via transplacental passage of a maternal IgG antibody against a fetal red blood cell antigen. The exception is the pathogenesis of fetal anaemia by Kell antibodies in which an additional mechanism is employed and erythrocyte production is suppressed at the level of the progenitor cell.2 It is thought this erythroid suppression is, in fact, the predominant mechanism in producing fetal anaemia in the case of the presence of Kell antibodies.3,8

The introduction of routine screening for maternal antibodies in the 1970s, in order to allow the early identification of those babies at risk and therefore allowing the opportunity for treatment, has led to an impressive decline in the incidence of fetal loss related to haemolysis.6 At this point, guidelines suggest repeated screening throughout pregnancy in Rhesus-positive women with no abnormal antibodies detected is not cost-effective given the incidence of late-onset alloimmunisation is extremely low.2

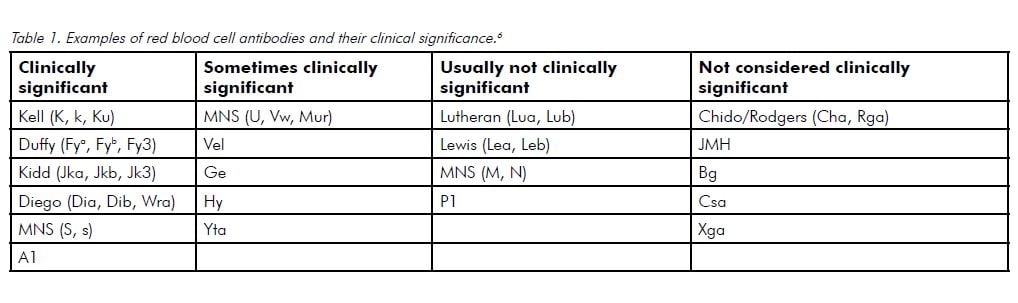

The approach to discovering an unusual antibody on a routine group and screen should be systematic and stepwise. The potential impact on the baby’s condition depends on the antibody type, their circulating levels in the maternal blood and the red blood cell antigens the fetus has inherited. If the antibody identified has not been indicated to be responsible for haemolytic disease of the newborn then generally no further evaluation is required (see Table 1).2 However, given the presence of antibodies hints at the possibility of exposure of the fetal blood to the maternal circulation, on-going consideration should be given to the possibility of fetomaternal haemorrhage, even if the antibody itself is not potentially harmful. If the antibody could result in an affected neonate, a thorough history should be obtained in order to better clarify the potential severity of impact on the current pregnancy. Important components include information regarding previous pregnancies and whether or not they were affected, and the defining of the mother’s transfusion history or the use of any illicit drugs.2 Paternal red blood cell antigen status and his zygosity for the antigen is extremely helpful in order to determine the next appropriate step.5 If the father is antigen-negative and his paternity can be guaranteed, then no further evaluation is required as this ensures the fetus will also be negative.2 If the father is antigen positive or his status is unknown, the fetus must be considered to be at risk.

It is generally advised, if these more unusual antibodies are detected in pregnancy, care should be the same as for women with Rhesus alloimmunisation.2 If clinically significant red blood cell antibodies are detected, regular fetal surveillance and follow-up is required. The next step should be a quantification of the antibody with a titre or equivalent quantification determined by a standardised technique. However, the general consensus is that serial titres are unnecessary prior to 18–20 weeks, owing to the low risk of fetal anaemia at this gestation.2 Titres should subsequently be monitored on a reasonable schedule; for example, repeated every four weeks until 28 weeks and then fortnightly until delivery.5 The regular monitoring of titres aids the clinician in determining when to initiate more intensive fetal monitoring. Approaches include ultrasound monitoring of the middle cerebral artery peak systolic velocity (MCA PSV), free fetal DNA, amniocentesis or cordocentesis, depending on the access in the facility managing the patient’s care.3 A titre of 1:16 is considered to be the level at which fetal anaemia

has occurred rarely in the past. A critical titre of 1:32 or higher necessitates an urgent evaluation for fetal anaemia with a referral to a maternal fetal medicine specialist.2 An exception to this rule is Kell, in which the critical titre is far lower at 1:8.2 If the patient has had a previous pregnancy affected by the antibody, it is important to remember the general rule is subsequent pregnancies are affected at a much earlier gestation.2 The conventional approach is to begin monitoring ten weeks earlier than the gestation at which the previous fetus was affected, with some maternal-fetal medicine specialists omitting the use of titres altogether and monitoring MCA PSV directly.9 Timing of delivery is dependent on the degree of fetal anaemia, the treatment required and the zygosity, with an attempt made to prolong gestation as close as possible to term.9

We now live in an age where obstetric intervention has thankfully all but prevented pregnancy loss owing to the Kell antibody, such as might have happened Henry VIII, and similar conditions. In its effect on this royal family 500 years ago, the Kell antibody may have played a covert, but important, role in history. Fortunately, despite these minor antibodies still being occasionally encountered in day-to-day practice, a precise and standardised approach to their management should ensure that a similar painful story will never happen again.

References

- Dean L. Blood Groups and Red Cell Antigens [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Center for Biotechnology Information (US); 2005. Chapter 4, Hemolytic disease of the newborn. Available from: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK2266/ .

- Barss V & Moise K. Significance of minor red blood cell antibodies during pregnancy [Internet]. UpToDate; c2012 [updated 2012 Nov 9]. Available from: www.uptodate.com/contents/significance-of-minor-red-blood-cell-antibodies-during-pregnancy?detectedLanguage=en&source=search_result&search=red+cell+antibodies&selected .

- Australian and New Zealand Society of Blood Transfusion Inc. Guidelines for Blood Grouping & Antibody Screening in the Antenatal & Perinatal Setting. 2nd ed. Sydney: 2004. Available from: www.anzsbt.org.au/publications/documents/ANGuidelines2004.pdf. [Expired link; search online at https://anzsbt.org.au/]

- Southern Medical University. Solving the puzzle of Henry VIII. 2011 Mar 03. Available from: http://phys.org/news/2011-03-puzzle-henry-viii.html .

- Leeds Pathology [Internet]. UK; Antibodies in Pregnancy [updated 2011 June 2]. Available from: www.pathology.leedsth.nhs.uk/pathology/ClinicalInfo/AntenatalTesting/AntibodiesinPregnancy.aspx

- Lab Tests online [Internet]. UK: RBC Antibody Identification [updated October 26 2011]. Available from: http://labtestsonline.org/understanding/analytes/rbc-antibody/tab/test .

- Whitley C & Kramer K. A New Explanation for the Reproductive Woes and midlife decline of Henry VIII. The Historical Journal. Dec 2010; 4: 827-848.

- Fortner, K, editor. The Johns Hopkins Manual of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2007.

- Wagle S. Haemolytic disease of the newborn treatment and management. May 2 2013. Available from: http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/974349-treatment .

Leave a Reply