Stillbirth is one of the most emotionally devastating pregnancy outcomes for patients, their families and healthcare providers.

In 2006, in Australia, stillbirth occurred at a rate of 7.4 per 1000 births.1,2 The management of stillbirth involves providing compassionate care, investigating for identifiable causes, managing delivery and providing postpartum care with ongoing support.

Antepartum management

Clinical history

Identification of a cause for stillbirth can help provide closure to grieving patients and their families, and can aid in the planning and management of future pregnancies.3,4 Thorough clinical history is a vital component of stillbirth evaluation. This includes past obstetric history, maternal medical history and antenatal history, noting any medical conditions complicating the pregnancy, anomalies identified on ultrasound, infections, abdominal trauma and exposure to toxins.3 Family history should include recurrent pregnancy losses, thromboembolic disorders, congenital abnormalities, hereditary conditions and consanguinity.3 An ultrasound scan is recommended to confirm the diagnosis of fetal demise, look for fetal anomalies and measure amniotic fluid volume.1,2

Karyotype

Fetal karyotyping should be encouraged. Abnormal karyotype is detected in 8–13 per cent of all stillbirths4 and in more than 20 per cent of those with structural anomalies or intrauterine growth restriction.4 Samples obtained antenatally via amniocentesis are more likely to yield viable cells for successful culture, than samples obtained from the placenta, cord or fetus after delivery (85–100 per cent versus 13–35 per cent).5 Amniocentesis can also provide a sample for microbiological culture. If amniocentesis is not possible, samples for karyotype can be taken from the placenta below the cord insertion site including the chorionic plate, an umbilical cord segment closest to the placenta, or fetal cartilage from the costochondral junction or patella.3,4 Fetal skin samples are suboptimal.4

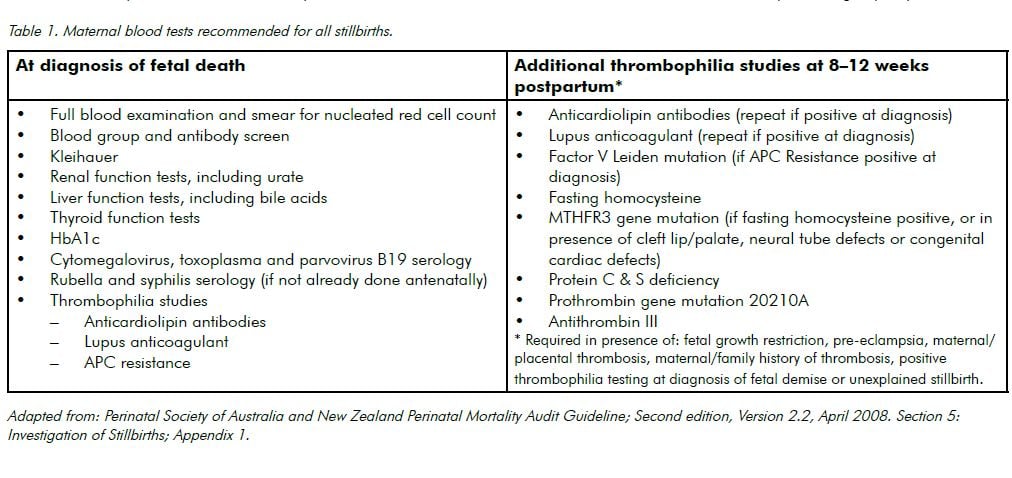

Maternal investigations

Maternal investigations taken prior to delivery may help to exclude many causes of intrauterine fetal demise. Recommended maternal blood tests are listed in Table 1. Low vaginal/peri-anal swabs should also be taken for culture.

Delivery

Environment

Where practicable, bereaved parents should be offered a private room away from other postnatal and antenatal patients. Continuity of care by midwifery, medical and support staff may also be helpful.

Timing

Timing and mode of delivery are dependent on gestational age, obstetric history, maternal preference and clinical circumstances.3,4 In most cases, there is no necessity for urgent delivery, however, a majority of patients prefer early delivery to expectant management. Around 80–90 per cent of patients will labour spontaneously within two weeks of fetal demise.4 Consumptive coagulopathy associated with prolonged fetal retention is due to thromboplastin release from the placenta. It is an uncommon occurrence3,4, particularly in the first four weeks after fetal demise.6

Mode of delivery

In general, vaginal delivery is preferable to caesarean section, as maternal risk minimisation is the main priority and fetal welfare is no longer an issue.3,4,2 However, patients should be managed on a case-by-case basis.

A 2010 Cochrane review compared vaginal misoprostol to other induction methods for termination of pregnancy in the second or third trimester for fetal demise or fetal anomalies. Vaginal misoprostol was as effective as other prostaglandin preparations and more effective than oral misoprostol in inducing labour and achieving vaginal birth within 24 hours. There were fewer maternal gastrointestinal side effects, but information on rare adverse outcomes, such as uterine rupture, was limited.7

Prior to 28 weeks gestation, vaginal misoprostol is generally the accepted method of induction. It has been shown to be 100 per cent effective in achieving vaginal delivery within 48 hours.8 Regimes vary between institutions, but are typically 200–400mcg vaginally every 4–12 hours.3 In patients with a prior uterine scar, evidence supports the use of vaginal misoprostol.3 Many institutions use a reduced dose protocol; however, as uterine rupture is such a rare event, data on the optimum dose and administration route are limited.3

Early stillbirths (less than 24 weeks) may be suitable for dilatation and curettage, however this requires an experienced operator and may limit the efficacy of autopsy for detecting gross fetal anomalies.3

After 28 weeks, either misoprostol or syntocinon are acceptable induction agents. Syntocinon dosing is in accordance with standard labour protocols and may be preceded by cervical ripening with misoprostol or dinoprostone (in patients without a uterine scar) or transcervical catheters (in patients with a uterine scar) where required.2 There is limited evidence regarding patients with previous classical caesarean section and such patients should be managed on an individual basis.3

Postpartum management

Placenta

Macroscopic and microscopic examination of the placenta, cord and membranes may reveal abruption, umbilical cord thrombosis, velamentous cord insertion or vasa praevia.4 Umbilical cord knots should be interpreted cautiously as most true knots are associated with live births.4 Swabs should be also taken for culture. Histology specimens should be submitted fresh and unfixed1, accompanied by appropriate clinical details.

Autopsy

Autopsy is perhaps the single most important investigation in the workup of a stillbirth.4 In 26–51 per cent of cases, it yields new information which influences counselling and future pregnancies.4 Autopsy findings can alter the estimated risk of recurrence of stillbirth and may change recommendations for future preconception, antenatal and neonatal management, as well as aid in the grieving process.9 When discussing autopsy, compassion and sensitivity are paramount. Its potential benefits should be discussed, while acknowledging and respecting the family’s personal, religious and cultural beliefs.4 This discussion should be provided by a senior clinician with sufficient understanding of the procedure involved.1 Many parents are not comfortable with a full autopsy and options for limited or step-wise autopsy should be discussed. This may include examination by a pathologist, clinical photography, full body X-ray, ultrasound scan or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).2 Ample time should be allowed for consideration and written information may be helpful. If desired, parents should also be given as much time as possible with their baby before autopsy. Written consent must be provided and should accompany the autopsy request, along with comprehensive clinical and obstetric histories and copies of the death certificate and ultrasound reports.

Regardless of whether or not an autopsy is requested, a detailed examination of the baby should be undertaken and any abnormalities photographed. Surface swabs (ear and throat) should also be obtained for culture.1 Cord or cardiac blood samples should be taken for microbiology, full blood count and Guthrie test.1

Counselling and support

Bereavement support officers are available in most hospitals and can serve as an individual point of contact to assist and support patients and their families in the early stages of grief.10 They can also provide advice on what to expect in hospital, legal requirements, funeral preparations and arrange support after discharge from hospital.10

There is a legal obligation to arrange a burial or cremation for all stillborn babies that are, by definition, born after 20 completed weeks of gestation or weighing 400g or more and showing no signs of life at birth.2 Birth registration is also required and social workers can assist patients in completing documentation and accessing government entitlements. They can also link patients with support groups, such as Sands, which provide support and information to parents and their families.11 All patients should also be offered psychological counselling.

Memories

For many parents, creating memories of their baby can assist in the grieving process.1 If desired, they should be allowed to parent their baby by holding, bathing and dressing them. Some parents may wish to take their baby home for a period of time and every effort should be made to accommodate this request. Cultural and religious beliefs should be respected and pastoral care referral offered if appropriate. Some families may wish to hold a baptism/ blessing while in hospital.

If a name has been chosen, health workers should refer to the baby by name.3 Special mementos such as cot cards, blankets, hand/ footprints and photographs can also be helpful in the grieving process.1 If parents do not wish to keep such mementos, they may be stored in the health record and parents advised that they can access them in the future, should they change their minds.2 Organisations such as Heartfelt offer free photographic memories to parents of stillborn babies.12

Follow-up

Where medically appropriate, early discharge with midwifery home follow-up should be offered.2 Lactation suppression and contraception are vital postpartum considerations, which should be discussed with all patients.2

Arrangements should be made for a follow-up consultation for results and counselling. This appointment should ideally take place within the first six to eight weeks.2 Patients should be made aware that even with thorough investigation, a cause for the stillbirth may not be identified.3,4 Referrals for genetic counselling and psychiatric services should also be considered where indicated.

The general practitioner should be advised of the death as early as possible and should be provided with a comprehensive clinical summary and results of investigations when available.

Risk of recurrence

The risk of recurrent stillbirth in future pregnancies will depend on the clinical circumstances and investigation results. Low-risk patients who have suffered an unexplained stillbirth, have a risk of recurrence of 7.8–10.5 per 1000.3 This rate may be higher for women with medical conditions or previous obstetric complications. Advice regarding management of future pregnancies should be individualised and is beyond the scope of this article.

As obstetricians, we will all encounter stillbirths during our careers. By providing appropriate medical advice and treatment, along with sensitive care and support, we will hopefully offer some comfort to vulnerable patients and their families during what is likely to be one of the most difficult experiences of their lives.

References

- Flenady V, King JF, Charles A, Gardener G, Ellwood D, Day K, et al. for the Perinatal Society of Australia and New Zealand (1) Perinatal Mortality Group, 1 Clinical practice guideline for perinatal mortality. April 2009; version 2.2.

- Queensland Maternity and Neonatal Clinical Guideline: Stillbirth care. Guideline No MN11.24-V4-R16May 2011. Available at: http://www. health.qld.gov.au/qcg/documents/g_still5-0.pdf [link expired; now at https://www.health.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0023/143087/g-stillbirth.pdf]

- ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 102: management of stillbirth. Obstet Gynecol. 2009; 113(3):748-61.

- Silver RM, Heuser CC. Stillbirth workup and delivery management. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2010;53(3):681-90.

- Korteweg FJ, Bouman K, Erwich JJ, Timmer A, Veeger NJ, Ravise JM et al. Cytogenetic analysis after evaluation of 750 fetal deaths: proposal for diagnostic workup. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111(4):865-74.

- Maslow AD, Breen TW, Sarna MC, Soni AK, Watkins J, Oriol NE. Prevalence of coagulation abnormalities associated with intrauterine fetal death. Can J Anaesth. 1996;43(12):1237-43.

- Dodd JM, Crowther CA Misoprostol for induction of labour to terminate pregnancy in the second or third trimester for women with a fetal anomaly or after intrauterine fetal death. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2010; CD004901.

- Gomez Ponce de Leon R, Wing DA. Misoprostol for termination of pregnancy with intrauterine fetal demise in the second and third trimester of pregnancy – a systematic review. Contraception. 2009;79(4):259-71.

- Michalski ST, Porter J, Pauli RM. Costs and consequences of comprehensive stillbirth assessment. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186(5):1027-34.

- The Royal Women’s Hospital [Internet]. Melbourne: c2006 [updated 2013 May 29; cited 2013 Oct 11] Pregnancy and newborn loss. Available from [link expired]: www.thewomens.org.au/PregnancyNewbornLoss .

- Sands.org [Internet]. [cited 2013 Oct 11] Available from http://www. sands.org.au.

- Heartfelt.org [Internet]. [cited 2013 Oct 11] . Available from http://www.heartfelt.org.au.

Leave a Reply