The obstetrics and gynaecology workforce in Australia: factors shaping our future, and how we should respond.

If asked about ‘workforce’, many RANZCOG members and Trainees respond in numerical terms, perhaps adding some qualifiers on distribution, gender and age. Demographic changes, such as the preponderance of female Trainees, ageing of provincial Fellows and the urban concentration of our current Fellowship are well recognised, but difficult to qualify in terms of workforce supply. Workforce supply-and-demand parameters are pivotal to those who are either established in practice, training to enter the discipline or at a pre-vocational stage contemplating a career in O and G.

Any discussion of the O and G workforce in Australia will have as many unknown as known factors. This is not say we, as a profession, should retreat from an informed and active participation in workforce planning in all forums. However, contemporary debate extends well beyond simple undergraduate or vocational Trainee numbers and now focuses on the ‘training and vocational pipeline’ – describing a continuum from medical school through pre-vocational and vocational training (including sub-specialisation), including career longevity and patterns of work throughout a career.

Taking into account recruitment from overseas (both temporary and permanent migration), changes in work practices, potential reforms to models of care that may reduce the demand for specialist and GP obstetricians, as well as predictions of expressed demand for services as the population grows and ages, we face a very complex system that starts to resemble one of Bruce Petty’s legendary economic modelling cartoons of the 1980s.

In this short article I address some of the more relevant the issues affecting our workforce predictions over the next 12 years, with particular reference to the Health Workforce Australia (HWA) publication Health Workforce 2025 (HW2025) Volumes 1–3 with reference to p129–138 in Chapter 15, specifically dealing with the O and G workforce. The HWA documents and subsequent work plans outline the current and predicted scenarios as they relate to the various ‘levers’ of reform and change that might be enabled under the Federal Government’s agenda.

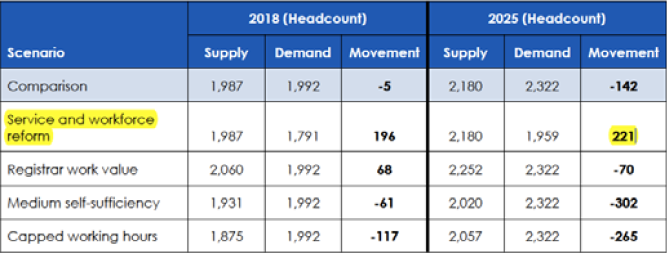

At the time of publication of the HWA report, in October of 2012, the workforce was estimated to be in undersupply.1 This formed the basis of the ‘comparison scenario’, (see ‘terminology’ below), under which we would remain under-supplied in 2025 by an estimated 142 specialists. Previous data collection and analysis by the Medical Training Review Panel (MTRP) have been more descriptive than predictive, but provided a valuable starting point for the HWA work.2

The MTRP was formed under legislation in 1996 to report to the Commonwealth Minister of Health on the activities of the MTRP and provide data on medical training opportunities in Australia. Over the years the panel has aimed, through its annual report, to provide a comprehensive picture of medical education and training, supplementing this with other data on the medical workforce supply.

Internal RANZCOG data on Practice Profile3 and Trainee intent4 complement those data and predictions. The most recent Practice Profile data gathered by the College, from May this year, include responses within the last three years from over 70 per cent of the Fellowship and confirm the trends and predictions expressed in the HW2025 publication. The practice intentions survey of Trainees and recently elevated Fellows contains more subjective data, with information on the reasons why our Trainees and recent graduates choose various career paths.

To appreciate the findings and recommendations of the HWA data it is necessary to understand both the terminology and methodologies used in describing workforce. Additionally, limitations of data collection and analysis should be noted to qualify interpretation of those data and guide any revisions between now and 2025. That said, our specialty poses particular challenges for workforce modelling and predictions. Some, like the long lead-time from undergraduate to Fellowship (15 years at the earliest), are common to most disciplines. Others, such as the impact of the feminisation of the workforce, changes in the models of care in obstetrics and, perhaps most importantly, the lack of inclusion of deliveries managed by GP obstetricians in the HW2025, make application of the HWA Work Plan5 to our profession more problematic.

Additional limitations in the O and G workforce data used by HWA in its modelling for the 2025 report must be acknowledged and include:

- failure to model IVF separately, as this is a recognised highgrowth area;

- lack of outpatient data for women’s health (a limitation common to most disciplines modelled by HWA); and

- the likelihood that the reported working hours for in O and G includes significant ‘on call’ hours, leading to over-estimation

- of true ‘time at work’. This may affect the ‘expressed demand’ calculations into the future.

Some specific terminologies are used when describing workforce parameters. These are described below in context with the Australian workforce and include:

- Comparison scenario – the ‘do nothing’ situation. This is an artificial construct used by analysts in which the current trends of demand, recruitment and migration are applied prospectively to the status quo in each profession.

- Expressed workforce demand – this important concept refers to predictions of the demand for services. There are several available methodologies for this indicator, with HWA adopting utilisation data that includes data on current services provided both in public (Diagnostic Related Groups and hospital separations) and private (Medicare data) sectors to predict future demand, taking into account predicted changes to disease burden, population and demographic changes. Expressed demand is estimated to grow by 2.6 per cent per annum. Specifically identified limitations to this measure with respect to expressed demand for O and G are the lack of data from outpatient services and the failure to account for GP obstetric services. Of note is that demand for medical services per se does not directly translate to workforce demand. In addition, new technologies and ways of managing reproductive health issues will inevitably modify this parameter. The interested reader is referred to HW2025 Vol 3 p393–71 for a more detailed explanation of expressed demand calculations.

- Self-sufficiency: measuring the impact of increasing, maintaining or reducing reliance on overseas-trained doctors leads to an estimation of self-sufficiency for each profession. HWA has identified our specialty as one of the disciplines more heavily reliant on specialist international medical graduate (SIMG) intake than others. During 2010–11, more than 45 per cent of the new Fellows elevated to FRANZCOG were from overseas. This indicator is a part of the overall workforce ‘vulnerability’ (see below).

- Workforce vulnerability, referring to demographic factors such as age, gender and working hours, measures the ability of a profession to respond in a timely manner to changes in demand, either increases or decreases. Firstly, we are ageing and this, in combination with changing work practices (shorter hours, more part-time work and parental leave), means that those who replace the retiring Fellows may not provide equivalent ‘supply’ on the capacity side of the equation. The average age of specialist O and Gs in the 2009 Australian Institute of Health Workforce (AIHW) survey was 51 years, with 37 per cent of Fellows aged 55 and over. One-third was female, and in 2010–11 more than 45 per cent of Fellows elevated to FRANZCOG were from overseas.

- Dynamic indicators refer to additional inputs, such as length of training and ability to replace exiting workers.

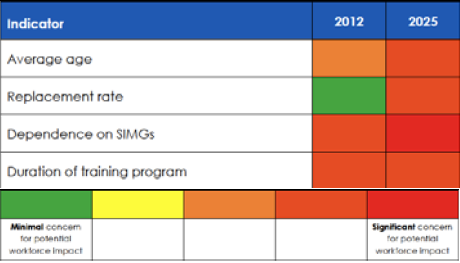

Figure 1. Summary of workforce dynamics indicators for O and G. © HWA 2012. Reproduced from Health Workforce 2025 Medical Specialties Vol 3 November 2012 with permission of Health Workforce Australia.

Figure 2. Summary of workforce supply and demand projections for O and G. © HWA 2012. Reproduced from Health Workforce 2025 Medical Specialties Vol 3 November 2012 with permission of Health Workforce Australia.

In summary, our specialty is rated as ‘vulnerable’ with respect to age, dependence on SIMGs and length of training, with the first two of these to become more dominant by 2025.

Figure 1 (taken from HW2025) indicates the grading by HWA of the dynamic indicators, where we are placed in 2012 and predicted to be in 2025. As can be seen, only ‘duration of training’ will not increase in severity or impact in the interval 2012–25. What, then, are the levers that can be manipulated to achieve a positive balance to meet the predicted expressed demand over the next decade?

Figure 2 (HW2025 Vol 3) shows the predicted workforce effects in 2018 and 2025 of the different ‘levers’ that may be used to adjust supply, against predicted demand. Of particular note to Fellows of our College, the only proposed reform that produces a positive balance in workforce is ‘service and workforce reform’.

Crucial to understanding and acting on the modelling by HWA for O and G workforce towards 2025 is an appreciation of the potential changes in the midwifery workforce with respect to the legislated (Maternity Reforms 2010)6 extended midwifery scope of practice, and the as-yet-to-be-modelled GP obstetrician contribution. With respect to the latter, very important challenges remain in both the training of GP obstetricians and providing ongoing support to these practitioners in often remote locations throughout Australia.

Lastly, we should examine how RANZCOG should respond to the workforce data, discussion and Health Department planning. Strategies could include:

- Proactive participation in discussions about productivity and efficiency, including new models of care.

- Ignoring the reality of work substitution, particularly in obstetrics, will likely result in our disenfranchisement from these reforms. Our College must continue to ensure that published data regarding better outcomes for women under specialist-led models of care are promoted and included in the reform agenda. As always, if we are not at the table, however disruptive to our work schedules this participation may be, we cannot object to the outcomes.

- Continue to make available, to HWA and the Commonwealth Health Department, the RANZCOG Practice Profile and practice intentions data, to ensure that policy decisions are informed, as far as is possible, by accurate and contemporary data.

- Request that any future modelling for the workforce takes into account GP obstetric contributions, particularly with respect to regional and rural expressed demand predictions.

- Continue to recognise and provide HWA with information on important issues such as mal-distribution of workforce, Indigenous health disparity and changing healthcare technologies specific to our field.

- Provide our own expert commentary on demographic modelling with respect to the population seeking reproductive healthcare.

- Provide HWA and other reform authorities with realistic and pragmatic appraisals of the potential role of: simulation in training, competency-based assessment for reducing length of training, job substitution and the ability to use training settings outside the traditional public hospital model.

- Remain actively engaged in the SIMG discussion, particularly with respect to plans to ‘streamline’ IMG entry to medical practice, along with active promotion of opportunities in our and other specialties.

- Re-assess demand for additional vocational training places in light of predicted under-supply, cognisant of the capacity restraints that may not be readily acknowledged by workforce planners.

It is of paramount importance that we, as a profession, remain aware of the planned government response to the findings and predictions of HW2025. The vulnerabilities identified for our profession will mean that the reform agenda will be relevant to how we train, assess and manage our workforce.

The National Health Workforce Innovation and Reform Strategic Framework for Action 2011–20157 has been approved by Health Ministers and will guide the policy formulation that seeks to address workforce issues around key domains including:

- Workforce capacity – including training numbers, skilled migration (which may include further streamlining of pathways to specialist registration for those disciplines perceived to have a high reliance on SIMGs) and retention within the workforce.

- Productivity – contained within this ‘reform’ we see the changing of maternity models of care, and the concept of ‘working to maximum license’, a term that, in our speciality, refers to an extension of midwifery roles in maternity care. Cost efficiencies and building a role for clinical assistants are also part of this domain.

- Improving distribution – this refers to both geographical distribution and the balance between generalist and sub-specialist. For us, it is critical that the GP obstetrician workforce is accounted for in future planning (it was not included in HW2025), and that we maintain a focus on generalist O and G training. Fortunately, this has been acknowledged as the preferred direction for the Australian medical workforce.

Accepting that a continued dependence on SIMGs is likely under the HW2025 scenario, it is imperative that the College provides sufficient resources to maintain a transparent, equitable and appropriately validated assessment process to ensure that those SIMGs elevated to Fellowship meet the standards expected by both the public and jurisdictional employers. Unlike some previous reforms in maternity care, we have a place at the table for this work and both the National Medical Training Advisory Network (NMTAN) and HWA will be expecting an active input from the College in the discussions and future directions of any reforms to the training and ‘vocational pipeline’ for all the specialties, including our own.

In some respects, this article is a call to arms to the Fellowship to engage in medical workforce reform, lest we be sidelined in the name of efficiency and task substitution, to the detriment of the standard of reproductive healthcare delivered in Australia. Doing nothing, and assuming that the status quo will serve either our patients or our own professional needs, is not an option. A reform agenda that affects our profession throughout the entire ‘pipeline’ is underway and perhaps only those who have already packed their fishing gear and taken down the brass plate can afford to remain disinterested and detached from these issues.

Changes in population demographics and continued demands for high-standard healthcare are perhaps the most reliable predictions for the next decade – it is the training methods, assessment tools and the nature of care providers that will inevitably change. Our challenge as a profession, and in particular for RANZCOG as a professional standards body, is to stay engaged with the agents of reform and remain a major partner in how reproductive healthcare is provided to future generations.

References

- Health Workforce Australia 2012: Health Workforce 2025 – Volume 3 – Medical Specialties.

- Medical Training Review Panel 15th Annual report available at http://www.health.gov.au/internet/publications/publishing.nsf/Content/work-pubs-mtrp-15-toc.

- 2013 RANZCOG Practice Profile.

- 2012 RANZCOG Workforce Intentions Survey.

- Health Workforce Australia 2012-13 Work Plan.

- National Maternity Services Plan 2010 (available at http://www. health.gov.au/internet/publications/publishing.nsf/Content/pacd-maternityservicesplan-toc).

- National Health Workforce Innovation and Reform Strategic Framework for Action 2011–2015.

Leave a Reply