In the puerperium, particularly following caesarean section, beware the postpartum distended abdomen.

Acute colonic pseudo-obstruction (ACPO) was first described in 1948 by the British surgeon Sir WH Ogilvie, who subsequently became the eponym of the condition. This acute surgical condition is classically described by massive colonic dilation in the absence of a mechanical cause. The exact pathophysiology is not fully understood, but if untreated the distension can result in rupture or ischaemic perforation of the bowel. We describe a recent case of Ogilvie’s syndrome in a postpartum patient, review the literature on the condition regarding its diagnosis and management, and discuss the syndrome’s relevance in obstetric practice.

Case report

A 43-year-old woman underwent an elective repeat caesarean section together with tubal ligation at 39 weeks gestation. The indication was maternal request for caesarean delivery and desire for a permanent method of contraception. The procedure was performed under regional anaesthesia (L3-L4 spinal block). There were no intra-operative problems noted.

During the first 24 hours, the woman used patient-controlled epidural anaesthesia (PCEA). This was removed on day two and the woman commenced regular oral analgesia. The patient remained well for the first 48 hours, but then reported spasmodic discomfort in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen and increased difficulty passing flatus with no bowel motion for four days. There was no associated nausea or vomiting and vital signs were all within the normal range.

Examination revealed a hyper-resonant and distended abdomen, upper abdominal tenderness and reduced bowel sounds. A working diagnosis of ileus was made and a full blood count, urea and electrolytes, liver function tests, C-reactive protein (see Table 1) and urgent erect and supine abdominal x rays were ordered. The radiographs showed a 13cm dilated caecal colon and 8cm dilated transverse colon (see Figure 1). The patient was discussed during the consultant ward round and, as the diagnosis was strongly suggestive of Ogilvie’s syndrome, the patient was transferred to the general surgical unit in the nearest hospital.

The surgical team ordered a pelvic and abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan that confirmed the initial radiological findings without any evidence of a transitional point; this made a functional cause of obstruction unlikely (see Figure 2). The surgical team initiated conservative management by restricting oral intake, providing intravenous hydration and inserting a flatus tube and regular enemas to encourage bowel activity. Over the next 24 hours, the patient started to pass flatus and decompress her bowel. The patient was discharged home on day six and given a follow-up appointment by the obstetric team for a debrief about her condition and its management.

Discussion and review

Since first being described in patients with retroperitoneal malignancy and involvement of the celiac plexus1, ACPO has now been reported in a wide variety of clinical conditions. The largest case series2 quotes a mortality rate of 15 per cent if diagnosed early and more than 40 per cent if the condition develops to the stage of bowel ischaemia.

The true incidence is unknown, but a large case series2 estimated that ten per cent of ACPO cases occur in O and G patients. The importance of ACPO in obstetrics was underlined by the UK Confidential Enquiry into Maternal Deaths Report 2000–20023, which reported three deaths from the condition during that triennium. Notably, after the condition was discussed in the CEMACH report, in the next triennium there were no reported deaths from the condition. In 2010, Rawlings4 published a case series of obstetric patients with Ogilvie’s syndrome that demonstrated early recognition of the condition, and thus early management, had a clear benefit in terms of decreasing associated morbidity. The findings from CEMACH and Rawling’s paper suggest that clinician awareness of ACPO is an important strategy in minimising patient morbidity.

Table 1. Haematological and biochemical results.

| FBC | U/E | LFT |

|---|---|---|

| Hb 148 g/L | Urea 4.1mmol/L | Bili 16umol/L |

| WC 16.9×10*9/L | Cr 46 umol/L | ALT 16umol/L |

| Neut 14.99×10*9/L | Potassium 4.2mmol/L | GGT 13U/L |

| GGT 13U/L | Sodium 133mmol/L | Alk phos 151U/L |

| CRP 309 | Bicarbonate 21mmol/L | Lipase 22U/L |

Figure 1. Plain film abdomen showing distended caecum in Ogilvie’s syndrome.

Figure 2. CT scan showing a coronal section of large bowel in a postpartum patient with Ogilvie’s Syndrome.

The pathophysiology of Ogilvie’s syndrome is uncertain. There appears to be an autonomic dysfunction involving the parasympathetic and sympathetic innervation of the colon. The parasympathetic innervation of the colon is supplied by the Vagus nerve until the splenic flexure, thereafter the parasympathetic supply to the distal colon is from the sacral spinal cord S2-4. The sympathetic innervation of the colon is via the celiac and mesenteric ganglia. One hypothesis for the cause of ACPO is that transient parasympathetic impairment at the sacral plexus may cause atony of the distal large bowel (beyond the splenic flexure), which could result in functional obstruction.5 Alternatively, increased sympathetic drive can be stimulated by bowel distension that will impair motility (colo-colonic reflex) this can promote further distension, particularly if the ileo-caecal valve is competent.5 By whichever mechanism, the resultant large bowel functional obstruction results in significant volume depletion (third spacing) and gaseous distension, owing to the bacterial decomposition of the static intra-abdominal contents. The caecum has the largest diameter of the colon, hence it dilates more rapidly than the remainder of the large bowel. If left untreated the caecum can rupture because of mechanical stretching or undergo ischaemic necrosis, whereby the pressure in the caecal bowel wall impedes vascular blood supply, eventually resulting in perforation.

Clinical presentation in obstetrics

ACPO has been reported to occur in women having a vaginal delivery, instrumental delivery and also antenatally with complicated pregnancies.6-8 However, the most common clinical scenario seen is in women after caesarean section.6 Typically, patients present with symptoms of increasing abdominal pain (reported in 80 per cent of cases). In these patients, nausea, abdominal distension and failure to pass flatus or stools should raise suspicion of the condition. The onset of these symptoms may vary from as early as day two to 12 days after delivery.6

Diagnosis

Once Ogilvie’s syndrome is suspected clinically, it should be confirmed radiologically. Colonic dilatation of more than 10cm is a significant marker of morbidity.5,8 A plain abdominal x ray is the most useful investigation to perform, the radiation dose of this procedure is 0.7mSV, (equivalent to five mammograms).9 It is imperative to rule out a mechanical or other cause of obstruction or infection with C. difficile (toxic megacolon). Ogilvie’s syndrome may mimic other conditions such as bowel perforation, bowel ischaemia10, sigmoid volvulus, peritonitis and so forth.6

Management

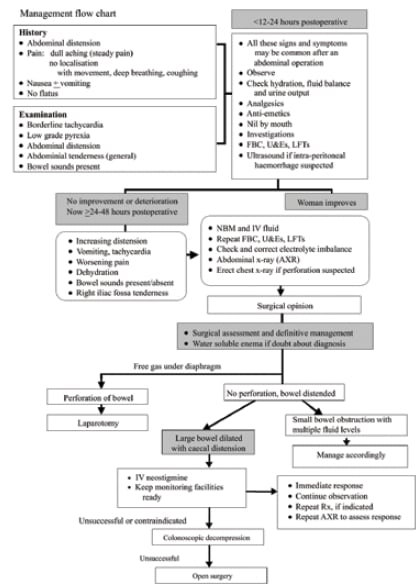

The management of Ogilvie’s syndrome consists of conservative, medical and/or invasive procedures (see Figure 3).6

Conservative management

This is appropriate for patients with a caecal diameter of 10cm or less and has a success rate of 96 per cent.5,6 It involves intravenous hydration, restricted oral intake, correction of electrolyte disturbances, nasogastric tube insertion, rectal tube insertion for decompression and urinary catheterisation to monitor output. Medications that interfere with gut motility (for example, opiates and anticholinergics) should be avoided. A conservative approach may be trialled for one to two days. Response is measured subjectively by the patient’s clinical condition and objectively by abdominal x rays.5,6

Medical management

Neostigmine (a reversible acetylcholinersterase inhibitor that stimulates the colon) is the best evaluated medical treatment with published success rates of up to 50 per cent of patients.11,12 Neostigmine is recommended for patients who do not require urgent decompression or have any contraindications to its use (perforation, mechanical intestinal and/or urinary obstruction). The drug can be given as a parenteral injection or as an infusion. Signs of resolution of ACPO may be observed within 30 minutes of administration, but usually more than one dose is required.6

Medical management

Neostigmine (a reversible acetylcholinersterase inhibitor that stimulates the colon) is the best evaluated medical treatment with published success rates of up to 50 per cent of patients.11,12 Neostigmine is recommended for patients who do not require urgent decompression or have any contraindications to its use (perforation, mechanical intestinal and/or urinary obstruction). The drug can be given as a parenteral injection or as an infusion. Signs of resolution of ACPO may be observed within 30 minutes of administration, but usually more than one dose is required.6

Invasive procedures

Colonoscopic decompression is the third-line management for Ogilvie’s syndrome. It is recommended in patients where conservative and medical treatment has failed. It has a reported success rate of 88 per cent.13 Complications include failure to decompress, relapse (40 per cent) and perforation (three per cent).5,6,14 Surgical therapy is the last line of treatment for Ogilvie’s syndrome. It is indicated for patients who fail conservative, medical and endoscopic decompression, or for the critically ill with complications of Ogilvie’s syndrome such as perforation or bowel ischaemia. It usually involves resection of the damaged bowel and stoma placement.6 Surgical treatment has a high morbidity, with a mortality rate of 30 per cent.2

Figure 3. Treatment algorithm for Ogilvie’s syndrome. Reproduced with permission from The Obstetrician and Gynaecologist.6

Follow-up

Previously healthy mothers who suffer from Ogilvie’s syndrome may require significant counselling and psychological support, this is particularly pertinent for patients who experience a delay in diagnosis or who have significant complications from ACPO. A discharge plan with a follow-up to debrief the patient and her family is sensible.

Conclusion

Ogilvie’s syndrome is a rare, but important, diagnosis to be aware of in obstetrics owing to its high morbidity and mortality. Any woman with abdominal distension in the early puerperium should be thoroughly reviewed and ACPO considered. A plain abdominal x ray is the most useful investigation to perform.5 If diagnosed early, conservative management is often successful and morbidity is minimal.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank the patient JM for permitting details of her care to be published.

References

- Ogilvie WH. Large-intestine colic due to sympathetic deprivation. Br Med J. 1948;2:671-3.

- Vanek VW, Al-Salti M. Acute pseudo-obstruction of the colon (Ogilvie’s Syndrome). An analysis of 400 cases. Dis Colon Rectum.1986;29:203-10.

- Lewis G.(ed.). The Confidential Enquiry into Maternal and Child Health (CEMACH). Why mothers die 2000-2002. The Sixth Report on Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths in the United Kingdom.London: RCOG Press, 2004.

- Rawlings C. Management of postcaesarean Ogilvie’s syndrome and their subsequent outcomes. ANZJOG 2010;50:573-574.

- Saunders MD, Kimmey MB. Systematic review: Acute Colonic Pseudo-obstruction. Division of Gastroenterology. University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005 Nov 15;22(10):917-25.

- Kakarla A, Posnett H, Jain A, George M, Ash A. Acute colonic pseudo-obstruction after caesarean section. The Obstetrician and Gynaecologist. 2006;8:207-213.

- Cartlidg D, Seenath M. Case report: Acute pseudo-obstruction of the large bowel with caecal perforation following normal vaginal delivery:a case report. J of Medical Case Reports. 2010;4:123.

- K akarla A, Posnett H, Jain A, Ash A. Acute pseudo-obstruction of the colon (Ogilvie’s syndrome) following instrumental vaginal delivery. Int Jof Clin Practice 60.(2006):1303-1305.

- Wall BF, Hart D. Revised radiation doses for typical x ray examinations.The British J of Radiology. 1997;70:437-439; (5,000 patient dose measurements from 375 hospitals).

- McGurgan P, Holohan M, McKenna P, Gorey TF. Idiopathic mesentericthrombosis following Caesarean section. Irish J of Med Sci.1999;168,3:164-166.

- Abeyta BJ, Albrecht RM, Schermer CR. Retrospective study of neostigmine for the treatment of acute colonic pseudo-obstruction. Am Surg. 2001;67:265-8.

- De Giorgio R, Barbara G, Stnahellini V, Tonini M, Vasina V, Cola B, et al. The Pharmacologic Treatment of Acute Colonic Pseudo-Obstruction. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15:1717-27.

- Geller A, Petersen BT, Gostout CJ. Endoscopic decompression for acute colonic pseudo-obstruction. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;44:144-50.

- Hutchinson R, Griffiths C. Acute colonic pseudo-obstruction: a pharmacological approach. Ann R Coll Surg Eng. 1992;74:364-7.

My daughter has just had surgery for olgivie syndrome after giving birth through ceserian section. I would like more current information about this syndrome. What should we be looking for in her condition? Should she have regular blood tests? What about diet.

Please send me relevant & current information on olgivie syndrome.

Will my daughter be able to have a general anaesthetic in other procedures or does this mean she is high risk when it comes to procedures using general anaesthetic?

Hi Della,

Thank you for your comments. Unfortunately, we cannot supply patient information or respond to personal queries. Please discuss your concerns with your daughter’s clinicians.