How a project to treat pelvic organ prolapse in Nepal grew into an endeavour to build workforce capacity.

Australians for Women’s Health (A4WH) began its life as an organisation whose sole function was to provide surgical camps to treat pelvic organ prolapse (POP) in remote areas of Nepal. Its original name was ‘Prolapse Down Under’. Following the first prolapse camp in Solokhumbu, it was decided that the organisation could also assist in combating the other major female medical problem in Nepal: high levels of maternal mortality.

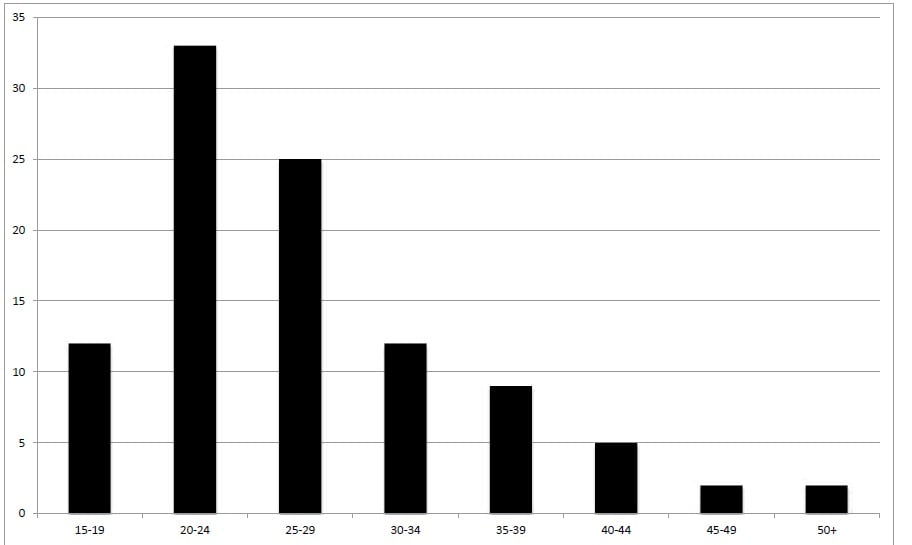

Nepal has a staggeringly high prevalence of POP. The World Health Organisation (WHO) estimates more than 600 000 Nepalese women suffer with some form of ‘uterine prolapse’1, with almost 200 000 in urgent need of surgery.2 This translates to ten per cent of the reproductive-age population, however in some districts the prevalence is as high as 44.5 per cent.3 Furthermore, unlike Western countries, the majority of POP in Nepal occurs in relatively young women. Forty-five per cent of symptomatic POP occurs in women less than 24 years of age (see Figure 1).4,5 There are very few local doctors trained in pelvic floor surgery.

Nepal remains one of the poorest countries in the world, with 82 per cent of the population living in rural areas. Access to medical facilities is limited in these areas and the majority of the population depend on subsistence farming for their livelihood.

Severe forms of POP significantly limit the working capacities and sexual function of these women. As a result, many are deserted by their husbands or families.4,6 As with the problem of genital fistula, the severe prolapse problem results in significant humiliation and social stigma.

A4WH regularly takes teams of gynaecology surgeons, anaesthetists, nursing and ancillary staff to remote areas of Nepal to provide prolapse camps. Other semi-urgent gynaecological surgery is performed when necessary. A4WH is one of a number of local and international organisations providing surgical prolapse camps.

Figure 1. Percentage age distribution of uterine prolapse onset in Nepal. Adapted from Pradhan, 2007.5

Conditions in prolapse camps are often quite challenging. The environment is often harsh, surgical facilities and equipment are limited. Electricity load shedding in Nepal means that power is unavailable for several hours each day at unpredictable times. Local electricity generators are either unreliable or absent and it is not unusual to operate under torchlight.

Pathology laboratories provide basic haematology and biochemistry, but many camps do not have readily available blood banks. Pre-operative pathology includes blood typing and, in the rare event of the need for blood transfusion, whole blood from a local relative or team member is used.

A4WH camps last two to three weeks to allow volunteers to coordinate their annual leave. Despite the considerable challenges of each prolapse camp, the mood of each team is remarkably upbeat. There is a wonderful camaraderie among the team.

Prolapse: why so many, and why so young?

Several qualitative studies have shown POP in Nepal is associated with a number of conditions. The most common associations are heavy workload during pregnancy and the immediate postpartum period, absence of skilled birth attendants (SBAs) at birth and poor diet.7,8,9

Measures designed to reduce the incidence of POP must include public health strategies to prevent the condition. However, public education alone is not enough to overcome firmly entrenched behaviour in rural areas of Nepal. Patriarchal and gender discrimination are major social determinants of POP in this country.10 Women are often expected to return to heavy working duties, often within one week of childbirth.11

Two of the guiding principles of volunteer work that are instilled into volunteers at A4WH are:

- do not interfere with the local traditions and customs; and

- do not tolerate the abuse of human rights.

Clearly there are times when these two principles are in direct conflict with each other. How to resolve this dilemma?

The more important of the two principles is to stand against the human rights abuse inherent in gender inequity. However, external intervention in social and cultural institutions is particularly challenging, because these are highly sensitive areas and involvement could easily be viewed as ‘cultural imperialism’. Proposing this form of social change is not an erosion of cultural liberty; rather it allows women freedom of choice. Promoting gender equality and the empowerment of women is not a ‘Western’ view imposed on developing countries; all 191 member states of the United Nations unanimously adopted this undertaking in the United Nations Development Declaration (MDG 3).12

As far as possible, attempts to promote healthy behaviour requiring cultural change are achieved through the use of local Nepalese intermediaries – people who share our own beliefs in gender equality and women’s health. During A4WH camps, selected respected locals are instructed to instruct households in health education, including the necessity of appropriate rest during and following childbirth or surgery; and the importance of antenatal care and SBAs at birth and during the puerperium.

In 2012, only 19 per cent of births in rural Nepal were attended by an SBA. A4WH is involved in a number of projects aimed at increasing the proportion of deliveries attended by SBAs.

Daily blackouts add to the challenge of performing any surgical procedure.

Severe uterovaginal prolapse in a 28-year-old woman.

Criticism of prolapse camps

Studies following government and non-government prolapse camps have been limited. Criticism has been applied in a number of areas. Qualitative studies from some of these camps have shown that preoperative counselling is often poor, with up to 20 per cent of women having no understanding of the surgery provided.4 Intermediate and longer-term postoperative follow-up is often lacking. There is concern that in a number of prolapse camps, the surgical treatment of severe forms of POP has been by vaginal hysterectomy alone, with minimal attention to the vaginal walls and vault – the so called ‘trophy hysterectomy’ camps.13,14 There is understandable apprehension that in the near future many women from these camps will present with prolapse of the vaginal wall and/or vault.

The A4WH prolapse camp

All patients undergo screening for significant POP and co-morbidities. In every A4WH prolapse camp it is a prerequisite that thorough, translated pre-operative counselling and information, education and communication (IEC) materials are provided to all women contemplating surgery. All patients undergo a pre-operative Quality of Life (QoL) questionnaire, and as many patients as possible undergo a post-operative QoL assessment six- to 12-months after surgery. Locating patients in remote areas several months post-operatively is often a difficult exercise and, to date, only 43 per cent of patients have undergone formal post-operative QoL assessment. Results show that 92 per cent of patients who have undergone prolapse surgery with A4WH are either satisfied or very satisfied. Data are continuing to be collected.

Maternal mortality in Nepal

Nepal shares many of the problems of other developing countries, including the absence of a vital register of births and deaths. As a result, the maternal mortality ratio (MMR) is an estimate only, based on extrapolations using the ‘sisterhood’ method. In 2009, the Nepalese Government reported the MMR to be 247 per 100 000 live births; however, the true figure may be significantly higher than this. Adjusting for the well-documented problems of underreporting and misclassification, in 2010, the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and WHO estimated the Nepal MMR to be 380 per 100 000 live births.15 As in all developing countries, the vast majority of causes of maternal deaths are preventable. A4WH is involved in a number of projects in an effort to reduce maternal mortality.

Antenatal clinics

While in developed countries antenatal care (ANC) has not been shown to reduce maternal mortality, it is generally agreed that in developing countries, where there is a higher prevalence of a number of potentially life-threatening conditions, ANC is highly likely to improve the MMR.16 In a country where education and the basic health of women and girls is poor, ANC provides the opportunity to teach hygiene, sanitation and nutrition, and to recognise specific pregnancy risk factors. Furthermore, in India, ANC has been shown to lead to a fourfold increase the SBA attendance at birth.17 Numerous international agencies have adopted SBA attendance as a leading indicator of maternal health.18,19

The original team in Phaplu, Nepal.

Hands-on antenatal ultrasound training.

In Nepal, there are many cultural and gender-based barriers preventing women from accessing ANC. Currently, only 28 per cent of women attend at least one antenatal visit18 (WHO currently recommends a minimum of four visits20). We have found that the provision of free antenatal ultrasound during ANC greatly increases attendance of both the woman and her husband.

A4WH is training Nepalese midwives in the provision of modern ANC. We also provide regular antenatal ultrasound training sessions to Nepalese midwives working in areas where formal ultrasound is unavailable. After three weeks of training, the majority of midwives are competent in the ultrasound diagnosis of many high-risk pregnancies including placenta praevia, multiple pregnancy, malpresentation and more severe forms of intrauterine growth restriction. A4WH ultrasound training camps will shortly be commencing in other countries.

Training local doctors

The long-term success of aid programs will only be achieved through sustainability. Training of local doctors (and other medical staff) is essential. During every camp A4WH teams train selected local surgeons in POP diagnosis, treatment and postoperative care. The challenge is to retain suitably trained doctors in rural and remote areas, as the large majority eventually choose to work in major cities in Nepal or other countries. We are currently undertaking discussions with the Nepal Ministry of Health regarding potential solutions to this problem, including three-year rural bonds for trainee local gynaecology surgeons.

The future

A4WH will continue to provide prolapse and maternal care camps, three to four times a year. Post-operative follow-up at 12 months of QoL and objective assessment be pursued with vigour.

A RANZCOG registrar exchange program is proposed for a teaching hospital in the mountainous district of Kavrepalanchok.A key to improving women’s health is to increase the level of education of both males and females. A4WH will shortly commence regular laptop computer training programs for local teachers in Nepal. Australian teacher volunteers will join surgical and maternal camps to instruct local primary school teachers in basic computer techniques. The Nepal Government has acquired a limited number of laptop computers for students in several schools in remote districts.

We are very fortunate and privileged to be living in a country where women’s health is of a very high quality. I believe that every one of us – practitioners experienced in women’s health – has a duty to contribute in some way to improving the health of women in countries like Nepal, where the quality of women’s health is appalling.

I founded the international aid organisation A4WH in 2010. The principles of A4WH are to provide pelvic floor surgery and to reduce maternal mortality in developing countries. Currently, the majority of the work is being performed in Nepal.

A4WH is continually seeking volunteers for its regular overseas activities. Volunteers include: gynaecologists experienced in POP surgery, anaesthetists, theatre nursing staff, midwives, ultrasonographers, school teachers and general hands. Potential volunteers should visit: www.A4WH.org.

A local midwife training session.

References

- Status of Reproductive Morbidities in Nepal. Available at: www.unfpanepal.org/pdf/Status per cent20of per cent20Reproductive per cent20Morbidities per cent20in per cent20Nepal_august per cent202 per cent202006_UN.pdf.

- United Nations Population Booklet on Uterine Prolapse (2007). Available at: www.advocacynet.org/modules/fck/u[load/file/upa/bonetti per cent20et per cent202004.pdf.

- Rai OA. Government lowers uterine prolapse treatment target. Republica, Jan 2010. Available at: http:/www.myrepublica.com/.portal/index.php?action=news_details&news_id=515.

- Chhetry DB, Upreti SR, Dangal G, Subedi PK, Khanal MN. Impact evaluation of uterine prolapse surgery in Nepalese Women. J Nepal Health Res Counc 2012 May;10(21):167-71.

- Pradhan S. Unheeded agonies: a study on uterine prolapse prevalence and its causes in Siraha and Saptari districts. Women’s Reproductive Rights Program, Centre for Agro-ecological Development, 2007.Available at: www.wrrpnepal.org/uploads/doc/46Unheeded per cent20Agonies-UP per cent20Survey per cent20Report.pdf.

- Bhattatai AM, editor. The landmark decisions of the supreme court, Nepal on gender justice.Hariharbhawan, Lalitpur Nepal: National Justicial Academy.

- Bodner-Adler B, Shrivastava C, Bodner K. Risk factors for uterine prolapse in Nepal. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct.

2007;18(11):1343-6. - Family Health Division, SAIPAL and WHO. Perception, experience and health outcome of the women who had undergone uterine prolapse surgery from Doti District of Nepal. Kathmandu: Family Health Division, South Asian Institute of Policy Analysis and Leadership (SAIPAL) and WHO Country Office Nepal; 2011.

- Earth B, Sthapit S. Uterine prolapse in rural Nepal: gender and humanrights implications; a mandate for development. J Cult Sex Health.2002;4(3):281-96

- Radl CM, Rajwar R, Aro AR. Uterine prolapse prevention in EasternNepal: the perspectives of women and health care professionals. Int JWomens Health. 2012; 4: 373–382. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S33564.

- Amatya S. Fallen womb: the hardest burden for a woman tobear. XLIII UN Chronicles 2006. Available at:www.um.org/pubs/chronicle/2006/issue3/0306p53.htm

- Jutting J, Morrison C. Culture, Gender and Growth. OECDDevelopment Centre Policy Insights No. 15). (Online) Available at:www.oecd.org/dev/35636812.pdf

- Rana A. Reducing morbidity from uterovaginal prolapse in Nepalesewomen through surgical camps: an ambitious approach. N. J. Obstet.Gynaecol. 2006:1(2);1-3 Nov-Dec 2006. doi:10.3126/njog.v1i2.1485.

- Gautam M. Uterine prolapse: Experts scorn health camp surgeries.The Kathmandu Post. Sept 15, 2011. Available at: www.ekantipur.com/the-kathmandu-post/2011/09/14/nation/uterine-prolapseexperts-scorn-health-camp-surgeries/226306.html

- UNICEF. New York, NY: United Nations Children’s Fund: 2010. Infoby Country: Nepal Statistics. (Online) Available at: www.unicef.org/infobycountry/nepal_nepal_statistics.html. Cited 21st Dec 2012 .

- Sharma SK. Does antenatal care matter reducing maternal mortality inNepal? J Pop Social Stud. 2006;14(2):59-76.

- Bloom, S., Lippeveld, T. Wypij, D. Does antenatal care make adifference to safe delivery? A study in Uttar Pradesh, India. HealthPolicy and Planning. 1999;14(1):38-48

- WHO, UNFPA, UNICEF, World Bank. Reducing maternal mortality:a joint statement by WHO/UNFPA/UNICEF/ World Bank. Geneva:World Health Organization; 1999.

- Campbell OMR, Graham WJ. The Lancet maternal survival seriessteering group. Strategies for reducing maternal mortality: getting onwith what works. Lancet. 2006:368;1284-99.

- World Health Organisation (2004). Far more pregnant women gettingantenatal care. (Online) Available at: www.who.int/mediacentre/releases/2004/pr22/en .

Leave a Reply