The Millennium Development Goals 4 and 5 provide a direction to achieve women’s and children’s well-being. The Global Strategy for Women’s and Children’s Health provides vital support to this, and catalyses worldwide action to accelerate progress towards achieving the MDGs. Many countries have recorded good progress, but much remains to be done.

Globally, under-five mortality has reduced by 35 per cent (1990–2010).1 More children survive today than they did a decade ago. In 1990, there were more than 12 million under-five deaths globally, but in 2010 this had reduced to 7.6 million. The child mortality rate dropped from 88 deaths per 1000 live births, in 1990, to 57 in 2010. Although the rate of decline at 2.5 per cent per year between 2000 and 2010, was an improvement from the 1.9 per cent year between 1990 and 2000, it is still insufficient to meet the MDG.4

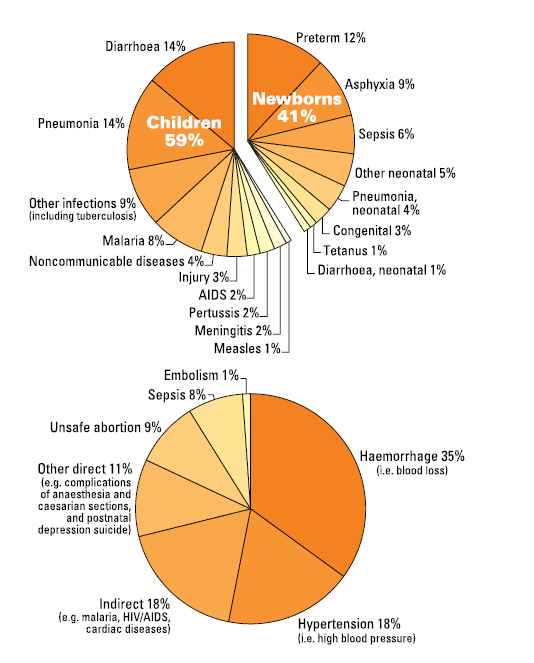

Newborn deaths (41 per cent) form the single largest category of deaths among under-fives.1,2 Preterm complications and birth asphyxia are the major causes for newborn deaths (see Figure 1).Pneumonia, diarrhoea, malaria and other infections such as tuberculosis, measles and so forth cause more than half the deaths in under-fives. Although not included in this category,as they are not counted as child deaths, there were 2.6 million stillbirths in 2008.3

In many countries, significant progress has been made to ensure child and maternal health is supported by the healthcare infrastructure.

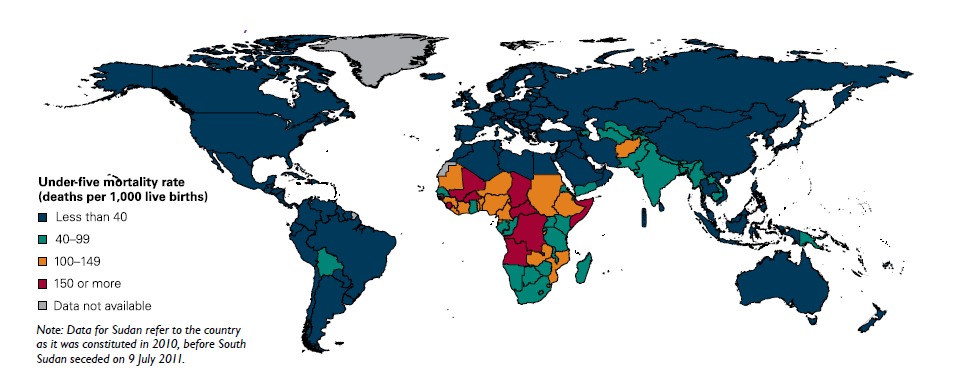

Under-five deaths have declined by at least 50 per cent in some countries, but continue to be particularly high in sub-Saharan Africa.1,4 About one in eight under-five children continue to die in sub-Saharan Africa, and one in 15 under-fives die in Southern Asia. Sub-Saharan Africa, with 121 deaths per 1000 live births, has nearly twice the average rate seen in low- and middle-income countries. But some large reductions have also been seen here between 1990 and 2010, as four sub-Saharan countries recorded the largest absolute reductions. India, Nigeria, Democratic Republic of Congo, Pakistan and China account for half the under-five deaths.1

Figure 1. Main causes of death. Top: Causes of deaths in children under five years (7.6 million deaths every year/ around 21 000 preventable deaths every day). Bottom: Causes of maternal deaths (350 000 deaths every year/ around 1000 preventable deaths every day). Adapted from: Countdown to 2015 (2010) and UN Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation (2011).

Figure 2. MDG 4: Child mortality rates. Source: UNICEF (2011). Levels & Trends in Child Mortality, 2011; Estimates developed by the UN Inter-agency. Group for Child Mortality Estimation (PDF). www.unicef.org/media/files/Child_Mortality_Report_2011_Final.pdf .

Children in rural areas and from the poorest households are vulnerable. Even in areas where child mortality rates could be generally low, poor children under-five years in rural areas are 1.7 times more likely to die than those in urban areas.1 Children from the poorest 20 per cent of households face more than twice the risk of dying as children in the richest 20 per cent of households.

Children of mothers with secondary or higher education face less risk of dying.1,4 Basic primary education among mothers brings down child mortality rates, but with secondary or higher education the reductions are much more significant.

The chances of survival are almost two-fold higher if a child’s mother has secondary education. For example, in Latin America and the Caribbean, the ratio of under-five mortality among children who had mothers with no education to that of those with primary education is 1.6.4

This ratio increases to 3.1 between mothers with no education and those with secondary education, implying that higher educational levels bring larger benefits.

Maternal mortality rates in low- and middle-income countries dropped by 34 per cent (1990–2008).4,5 Despite a significant drop from 440 maternal deaths per 100 000 live births in 1990, to 290 deaths in 2008, the progress in low- and middle-income countries is not at a rate that can achieve the MDG. The progress has been uneven across regions with some regions such as Eastern Asia, Northern Africa, South-Eastern Asia and Southern Asia reporting reductions of 40 per cent or more, while others such as sub-Saharan Africa showing only a 26 per cent reduction.

About 87 per cent of maternal deaths happen in South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa (2008).5 South Asia has shown a 53 per cent reduction (1990 to 2008), but is still host to a large number of maternal deaths. With maternal mortality rates of 280 deaths per 100 000 live births and 640 deaths per 100 000 live births, South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, respectively, bear the largest burden of maternal deaths in the world (see Figure 3).

More than 50 per cent of maternal deaths are due to haemorrhage and hypertension.6 This high proportion of deaths due to haemorrhage and hypertension reflects the poor access to basic as well as emergency obstetric care. Unsafe abortions, which are also preventable, account for nine per cent of maternal deaths. About a fifth of the maternal deaths are due to indirect causes such as cardiac diseases, malaria, HIV/AIDS, etc. (see Figure 1).

Skilled birth attendance in low- and middle-income countries increased from 55–65 per cent (1990–2009).4 There has been significant progress in many regions, but that is not enough yet. For example, in South Asia, skilled birth attendance improved from 32–50 per cent (1990 to 2009), but coverage is still low here as well as in sub-Saharan Africa (46 per cent).

The proportion of women who received care from a skilled health worker at least once during pregnancy increased from 64 to 81 per cent (1990 to 2009), but the proportion of those who had the recommended four contacts is only 51 per cent.4

South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa have the lowest antenatal coverage. In South Asia the coverage for at least one contact is 70 per cent, while that for four contacts is 44 per cent. If India is excluded, the proportion of women having four contacts goes down to 26 per cent in this region.

Childbearing among teenagers in low- and middle-income countries continues to be high at 54 per cent (2008).4 Overall, teenage childbearing decreased between 1990 and 2000. But the rate of decline slowed down between 2000 and 2008, and in some places childbearing in this age group has actually increased. In sub-Saharan Africa, however, there has been little change in the past two decades and it still records the highest rate (122 births per 1000 women aged 15 to 19 years).

Although 61 per cent of all married women or those with a partner (15 to 49 years) use contraception (2008), unmet need is high in some areas.4 In sub-Saharan Africa in 2008, only 22 per cent of women in the above category used any contraception. And the proportion of women in sub-Saharan Africa who wished to delay or avoid pregnancy, but did not use any contraception, was 25 per cent. These facts point to the low contraceptive prevalence in this region. Donor aid for family planning services as a proportion of total healthcare aid decreased from 8.2 to 2.6 per cent between 2000 and 2009.

The sub-Saharan region is home to the highest maternal mortality rates and teenage pregnancy rates, lowest rates of skilled birth attendance and contraception prevalence, making it the most unsafe place for a woman to become pregnant. With a growing population in the childbearing age group in low- and middle income countries, the pressure on reproductive and maternal health services is set to increase. If the current trend of dwindling funds to reproductive health and family services continues, it could exacerbate the high rates of teenage pregnancies and low contraceptive use/prevalence – potentially leading to unsafe abortions and maternal deaths.

Poverty and lack of education are key determinants of under five mortality rates, high rate of teenage pregnancies, low contraceptive use, lack of access to skilled birth attendance, undernourishment among children, lack of access to clean drinking water and proper sanitation. Improvements in these two key determinants can help accelerate progress in other areas.

This is an edited version of the PMNCH Knowledge Summary 1: Women’s & Children’s Health: Progress Towards MDGs 4 and 5, which is available to download.

Leave a Reply