The story of performing caesarean section in 19th-century Africa has some surprising twists and turns.

Although exact records are lacking, it has been widely accepted in relevant literature that at some time between 1815 and 1821 a caesarean section operation was performed in Cape Town, South Africa, by a British military surgeon, Dr James Barry. While the date of this procedure is uncertain, the name of the infant, James Barry Munnik, is well documented, the child being named for the surgeon. It has been further claimed that this was the first successful caesarean section in Africa – successful in that both mother and child survived – and also the first such successful caesarean performed by a British doctor.

Yet, while details of the operation are scant, the surgeon has received a great deal of attention in recent years. For it has also been claimed that ‘Dr James Barry’ was actually a woman, and was therefore the first British woman to become a qualified medical doctor.

The person who later became known as Dr James Barry was born to Jeremiah and Mary-Ann Bulkley, probably in 1789, in Ireland. At the time of birth it appears the child was known as Margaret Ann Bulkley. Mary-Ann Bulkley’s maiden name was Barry, and her brother, James Barry was a well-known portrait painter at the time. In 1809, Margaret and Mary-Ann Bulkley travelled by sea to Edinburgh; from this point on no record exists of Margaret Bulkley, but a young (apparently male) James Barry was enrolled in the medical school of the University of Edinburgh later in 1809. James received his medical degree in 1812, and moved to London, becoming a pupil at both Guy’s and St Thomas’s hospitals, and successfully passing the examinations of the Royal College of Surgeons of England in 1813.

Later in 1813, Dr James Barry joined the British Army, serving first in South Africa. At some time between 1815 and 1817 he arrived in Cape Town, where he is said to have improved the water system as well as conditions both for wounded soldiers and for ‘the native population’. He continued his medical career in the army until 1864, serving in Malta, Canada, the West Indies and during the Crimean War, and was frequently noted for his concern for the poor and suffering who came under his care. Throughout his time in the army, he was always accepted, and identified himself, as a man. Although his achievements in public health and medical administration were well recognised, it was also said that he could be impatient and tactless, and that he had a tendency to meddle in local politics, and it is known that he fought at least two duels.

Retiring from the service in 1864, he died in 1865 of dysentery, at which point the charwoman employed to wash his body after death reported to the Registrar of Deaths that the body was that of ‘a perfect female’. Informed of this, the Army sealed the records for 100 years. In the mid 20th century, historians gained access to these records and there have been a number of biographies, plays and television documentaries on the subject of Dr James Barry. There have been claims that Barry was a normal female who had to disguise her gender in order to enter medical school, and was therefore the first British woman doctor. However, it seems more likely that James Barry had some form of intersex condition, and chose in his teenage years to identify as male.

But was the birth of James Barry Munnik really ‘the first successful caesarean section in Africa’? There is in fact some evidence to suggest the original inhabitants of that great continent may have worked out the benefits and techniques of the operation well before more ‘civilised’ European practitioners.

In 1884, in the Edinburgh Medical Journal, Dr RW Felkin described at length an operation he had witnessed in Uganda in 1879, performed by ‘a native surgeon’. The patient was a 20-year-old primipara in obstructed labour who, in the absence of the more conventional methods of anaesthesia by then widely used in Europe, was ‘reduced to a state of semi-intoxication’ by a large dose of banana wine. She was then tied to her bed with bands of cloth over her legs and chest, while an assistant held her feet. The surgeon, who would seem to have possessed more understanding of the principles of antisepsis then being promulgated by Joseph Lister than did many of Lister’s own colleagues, proceeded to paint the woman’s abdomen and wash his own hands with more of the banana wine.

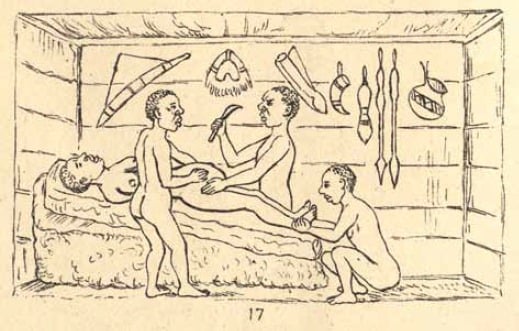

Caesarean section being performed in Kahura, Uganda, as described by Felkin.

He then made a rapid midline incision from umbilicus to symphysis, through the full thickness of the abdominal wall and part of the anterior surface of the uterus. Bleeding was dealt with by the cautious application of a red-hot iron to spurting vessels. The uterine incision was extended, the child extracted, in good condition, the cord cut, and placenta and blood clot removed manually. Uterine massage caused the organ to contract well and the iron was applied to deal with further minor bleeding. The uterine incision was not sutured but a ‘porous grass mat’ was placed over it and the woman turned on her front so that fluid could drain from the abdominal cavity.

Some short time later the woman was turned on to her back, the mat removed and ‘the edges of the abdominal wound brought into close apposition, seven thin iron spikes, well-polished and resembling acu-pressure needles, being used for the purpose and fastened by a string made from bark cloth.’ The wound was dressed with a concoction made from plant roots and firmly bound with a cloth. The woman, said Felkin, ‘stood the operation in silence until the pins were placed.’ Post-operatively the dressings were changed on alternate days and the pins gradually removed. There was very slight post-operative fever which quickly settled, the wound was well healed by day 11, and the patient appeared to have made an excellent recovery.

The first successful caesarean operation performed in Europe is widely acknowledged as being the caesarean hysterectomy performed by Edouardo Porro in Padua in 1876, both mother and child surviving. Successful classical caesareans were first reported from Germany by Sanger and Kehrer around 1882. While by 1879 ether and chloroform anaesthesia were being extensively used in European and North American surgical procedures, there was still widespread scepticism about the practices of antisepsis and asepsis. So while the ‘native surgeon’ Felkin observed may have learned a certain amount about avant-garde European practice from missionary doctors, it would seem from the timing and details of Felkin’s description that African practitioners had very likely developed their techniques of abdominal delivery quite independently, and much earlier than in Europe. Felkin himself concluded that these techniques had been employed for a very long time. Similar reports have come from Rwanda, where botanical preparations were used to anaesthetise the patient and promote wound healing.

So it seems that the identity of the original person to perform ‘the first successful caesarean section in Africa’ must remain unknown.

Acknowledgement

I would like to thank Ms Cheryl Brooking who first told me about the extraordinary life of James Barry.

Further reading

Rae, Isobel. The Strange Story of Dr James Barry. London: Longmans Green, 1958.

Du Preez HM. Dr James Barry: The Edinburgh Years. Journal of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh 2012; 42: 258-65.

Brandon S. James Barry. Oxford Dictionary of Biography. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004.

Felkin RW. Notes on labour in Central Africa. Edinburgh Medical Journal 1884; 20: 922-30.

National Institutes of Health. Cesarean section – a brief history. At www.nlm.nih.gov/exhibition/cesarean/part2.html .

Leave a Reply