This article presents the case of a pregnant patient who experienced significant discomfort from her previously inconspicuous axillary accessory breast tissue and reviews the aetiology and management of such presentations.

Accessory breast tissue – the presence of a nipple, areola or glandular tissue in addition to the normal pair of breasts – is an uncommon, but potentially painful and embarrassing, condition.

A 31-year-old Asian woman, gravida one para zero, booked into the antenatal clinic at 31 weeks gestation, having recently relocated to the area. She had an uncomplicated antenatal course, but was concerned about accessory breast tissue developing under her arms.

The patient had noticed this tissue as pale, bilateral axillary lumps when she was a teenager. She researched these herself, concluding that they were accessory nipples. She experienced mild, intermittent tenderness in association with some periods, but they did not otherwise concern her. However, at eight weeks gestation the patient noticed swelling under and around the nipples. As her pregnancy progressed, the accessory areolae darkened and breast tissue increased significantly in size and tenderness (see Figure 1).

The woman had a routine post-dates induction of labour at 41 weeks plus five days and proceeded to a vacuum delivery (for prolonged second stage of labour) of a healthy 3170g baby girl.

The woman had attended breastfeeding classes antenatally and was reviewed by the lactation consultant following delivery. She was advised not to stimulate the accessory breasts, as that may encourage milk production in them.

The woman was discharged home on day two postpartum, breastfeeding well. On day four, she complained of pain and swelling in her axillae, with milk leaking from her accessory nipples. She was advised to use ice packs and simple analgesia. The pain subsided after one week, however she continued to have one teaspoon of milk leak from each accessory breast, each feed. At the time of writing, her daughter was seven weeks old and continuing to breastfeed well. Unfortunately, the leakage from the patient’s accessory breasts persisted.

The swelling, discomfort and lactation associated with her axillary polymastia have had a significant impact on the woman’s quality of life. She is determined to have the accessory tissue removed prior to future pregnancies.

Figure 1. The patient at 41 weeks gestation, with significant polymastia.

Classification

Accessory breast tissue presents in many forms, from inconspicuous accessory nipples to fully formed and functioning supernumerary breasts. Classification has historically been according to the classes developed by Kajava (1915)1 (see Table 2). However, authors more recently have adopted a simplified system, dividing accessory breast tissue into the following:

- Polymastia: glandular breast tissue in an organised ductal system, communicating with overlying skin.

- Polythelia: accessory nipples and/or areolae. The presence of an areola only or patch of hair only may be further categorised as polythelia areolaris and polythelia pilosa, respectively.

- Aberrant breast tissue: disorganised secretory tissue, unrelated to the overlying skin.2

Polythelia is the most common congenital breast abnormality, with an incidence of between two and ten per cent in the general population.3 It is found more commonly in Native American4 and Asian populations2 and less frequently among Caucasians.3 It is equally found in males and females.2

Polymastia is less common, with an incidence of 0.22 to six per cent in the general population.5 Again, it is more common in Asian populations (particularly the Japanese)6 and occurs in less than two per cent of Caucasians.7 It is twice as common in females as in males.8 Polymastia occurs bilaterally in one-third of affected persons and, if unilateral, is located on the right in 64 per cent of cases.9

Aetiology

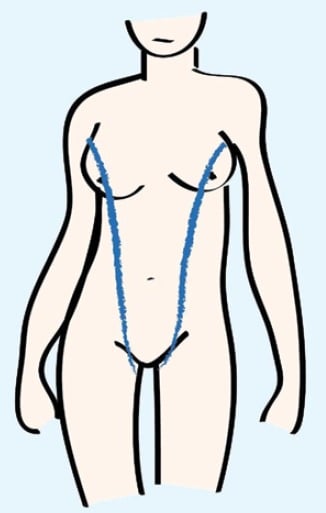

During the fifth week of gestation a thickening of ectoderm, known as the mammary ridge, appears on the ventral surface of the embryo. It correlates to a line from the axilla to the groin, called the milk line (see Figure 2). The mammary ridge regresses over the following months, with the exception of paired tissue on the anterior chest, which forms normal, pectoral breasts. Failure of this regression may result in accessory breast tissue.10

Figure 2. The milk line.

Accessory breast tissue may occur at any point along the milk line. Polymastia is most commonly found in the axilla (with an incidence of 60–70 per cent), as it did in the case above. However, it also occurs in the sternal region and on the vulva.8 Polythelia most frequently occurs in the sternal region.11 Very rarely, accessory breast tissue may occur outside of the milk line, a phenomenon known as mammae erraticae. Cases have been reported on the buttocks, neck, face, arms, hips and back.10

There appears to be some genetic contribution to accessory breast tissue, likely through heterogeneous inheritance, with ten per cent of patients having an affected family member.5

Diagnosis

Accessory breast tissue is often inconspicuous until puberty or even pregnancy, when hormones – oestrogens, progesterones, prolactin and human placental lactogen, in particular – affect accessory breast tissue in the same way as in normal breast tissue. This may lead to development of the tissue, pain (especially during menstruation), restricted arm movement, cosmetic concerns, irritation from clothes and lactation.5,9 Pregnancy-related symptoms often become more severe with subsequent pregnancies.6

Polymastia and (to an even greater extent) aberrant breast tissue is often misdiagnosed as a lipoma, lymphadenopathy, sebaceous cyst or hidradenitis.2,5 Polythelia is commonly mistaken for a benign nevus.2

Tissue diagnosis is obviously the gold standard for accessory breast tissue. Pathologists may look for typical stroma, lobules and ducts, however these may be poorly organised in aberrant breast tissue.12,13 The presence of oestrogen and/or progesterone receptors is diagnostic of breast tissue.14

Complications

Accessory breast tissue is susceptible to the same disease processes as normal breast tissue, including malignancies, benign cysts, fibroadenomas (which often occur in conjunction with fibroadenomas in the normal breasts) and mastitis.10

The incidence of malignancies in accessory breasts has been reported as higher than that in pectoral breasts and accounts for 0.2–0.6 per cent of all breast cancers.7,13 Authors have suggested this increased incidence may be due to ‘stagnation’ in the ducts. Ductal cancer is the most common type of accessory breast cancer, with infiltrating ductal cancer representing 79 per cent of accessory breast malignancies. Medullary cancer, lobular cancer and Paget’s Disease also occur. The axilla is the most common site for accessory breast malignancies, accounting for 55–91 per cent of presentations.13

Women with accessory breasts should have them screened for malignancies, along with their normal breasts.14 While mammography does not usually pick up axillary accessory breast tissue, oblique and ‘exaggerated craniocaudal’ views may achieve satisfactory images. On mammogram, accessory breasts have the same appearance as normal breast tissue, but are separate from the pectoral breasts. Similarly, accessory breast tissue appears the same as normal breast tissue on ultrasound.15

Although data are limited, accessory breast cancer appears to have a poorer prognosis than cancer in pectoral breasts. Authors have theorised that this is because the cancer metastasises to lymph nodes more frequently and rapidly than that in regular breast tissue.16 However, others have suggested that the poorer outcomes are due to delayed diagnosis, attributable to diagnostic difficulties (especially relating to aberrant breast tissue), plus a lack of awareness in the medical community. This is supported by the finding that prognosis in accessory breast cancer does correlate to disease stage (which is often advanced when diagnosed).15

Polythethelia has been associated with renal problems (such as supernumerary kidneys and renal carcinoma) in a number of studies, with one reporting an incidence of renal defects of between one and two per cent in the general population, but 14.5 per cent in patients with accessory breast tissue.5,10 However, other studies show no correlation.17,18 It has also been speculated that this association is only valid for certain populations.17

There is a controversial association between accessory breast tissue and cardiovascular disorders (such as pulmonary hypertension, cardiomyopathy, hypertension and conduction disorders). Other correlations suggested in the literature – but not proven – include vertebral disease, pyloric stenosis, testicular cancer and even familial alcoholism.17

Management

For brevity, this section of the article will focus on the management of benign axillary accessory breast tissue, rather than the management of malignancies in accessory breast tissue, which are treated in a similar manner to pectoral breast cancers.15

There is no medical indication to remove benign axillary accessory breast tissue, although there are a number of aesthetic and pragmatic considerations.6 Studies have shown that the majority of patients presenting to surgeons for treatment have cosmetic concerns, while others experience difficulties with arm movement, engorgement during menstruation or are concerned regarding the potential for malignancy.18 One plastic surgeon has advocated routine pre-pubescent removal of accessory breast tissue, to avoid glandular development and its associated complications.19

Table 1. Classification of accessory breast tissue

| Class – Kajava (1915)1 | Contemporary nomenclature2 | Tissue present | ||

| Glandular tissue | Areola | Nipple | ||

| I | Polymastia | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| II | Yes | No | Yes | |

| III | Yes | Yes | No | |

| IV | Aberrant breast tissue | Yes (disorganised) | No | No |

| V | Polythelia | No | Yes | Yes |

| VI | No | No | Yes | |

| VII | No | Yes | No | |

| VIII (patch of hair only) | No | No | No | |

As recently as 15 years ago, management of axillary accessory breast tissue was largely by gross surgical excision. One study (of operations between 1993 and 2000) found a complication rate of 39 per cent, with unsightly scarring and residual tissue being the most common complaints. On the basis of the large number of patients presenting for cosmetic reasons, the authors of the study did not recommend surgical management.9

However, other studies – and particularly those published more recently – have reported higher patient satisfaction and lower adverse events. The more recent developments in surgical management include the use of liposuction (whether alone or after surgical tissue removal), utilising elliptical incisions along tension lines to reduce scar visibility and employing minimally invasive incisions.20,21 One study also advocated tissue reduction of the normal breasts at time of accessory breast removal (utilising the same incision), where patients desired this.18

In 2011, the American Society of Plastic Surgeons published an algorithm for treatment of axillary accessory breast tissue (see Table 2). It advocates a combination of surgical excision and liposuction, according to the features of the tissue.22

The patient in the case described above clearly fits into Type IV of this management algorithm and, according to recent literature, would benefit from surgical excision of the breast tissue, adjacent fat and skin, with cosmesis enhanced by the use of liposuction.

Conclusion

Accessory breast tissue, a fairly uncommon embryological defect, may present as inconspicuous polythelia or fully-formed polymastia. The latter in particular may cause significant discomfort and embarrassment for those affected. The breast tissue is also vulnerable to the same diseases – both benign and malignant – as normal breast tissue. It is therefore important for clinicians to be mindful of accessory breast tissue when investigating masses along the milk line (and particularly in the axilla). It is also important to consider the recent improvements in surgical management of accessory breast tissue when counselling patients. It is a combination of these factors that has led the patient described to seek referral for surgical excision, prior to her next pregnancy.

Table 2. Treatment of axillary accessory breast tissue. Adapted from Bartsich SA, Ofodile FA (2011).22

| Type | Features | Treatment | ||

| Size | Excess skin | Distinction from normal breast | ||

| I | Barely visible | None or little | Separate +/- central core | Direct excision without removal |

| II | Small mass | None or little | Contiguous | Suction lipectomy |

| III | Visible mass | Present | Contiguous | Suction lipectomy with skin excision |

| IV | Large mass | Present | Separate +/- central core | Surgical excision of tissue and skin +/- suction lipectomy |

References

- K ajava Y. The proportions of supernumerary nipples in the Finnishpopulation. Duodecim. 1915; 1:143-70. Reported in Lakkawar NJ,Maran G, Srinivasan S, Rangaswamy T. Accessory breast tissue in theaxilla in a puerperal woman – case study. AMM. 2010;49(4):45-7.

- Ghosn SH, Khatri KA, Bhawan J. Bilateral aberrant axillary breasttissue mimicking lipomas: a report of a case and review of theliterature. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34(Supp 1):9-13.

- Walker M. Breastfeeding management for the clinician: using theevidence. 2nd ed. Sudbury (MA): Jones and Bartlett; 2011.

- Gilmore HT, Milroy M, Mello BJ. Supernumerary nipples and accessorybreast tissue. S D J Med. 1996;49(5):149-51.

- Loukas M, Clarke P, Tubbs RS. Accessory breasts: a historical andcurrent perspective. Am Surg. 2007;73(5):525-8.

- Lakkawar NJ, Maran G, Srinivasan S, Rangaswamy T. Accessorybreast tissue in the axilla in a puerperal woman – case study. AMM.2010;49(4):45-7.

- Evans DM, Guyton DP. Carcinoma of the axillary breast. J Surg Oncol.1995;59(3):190-5.

- Burdick AE, Thomas KA, Welsh E, Powell J, Elgart GW. Axillarypolymastia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49(6):1154-6.

- Down S, Barr L, Baildam D, Bundred N. Management of accessorybreast tissue in the axilla. Br J Surg. 2003;90:1213-4.

- Grossl NA. Supernumary breast tissue: historical perspectives andclinical features. South Med J. 2000;93(1):29-32.

- Dixon JM, Mansel RE. ABC of breast diseases: congenital problemsand aberrations of normal breast development and involution. BMJ.1994; 309:797.

- Desai A, Ramesar K, Allan S, Marr A, Howlett D. Breast hamartomaarising in axillary ectopic breast tissue. Breast J. 2010;16(4):433-4.

- Caceres M, shih J, Eckert M, Gardner R. Metaplastic carcinoma in anectopic breast. South Med J. 2002;95(4):462-6.

- Coras B, Landthaler M, Hofstaedter F, Meisel C, Hohenleutner U.Fibroadenoma of the axilla. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31(9):1152-4.

- Nihon-Yanagi Y, Ueda T, Kameda N, Okazumi S. A case of ectopicbreast cancer with a literature review. Surg Oncol. 2011;20(1):35-42.

- Roorda AK, Hansen JP, Rider JA, Huang S, Rider DL. Ectopic breastcancer: special treatment considerations in the postmenopausalpatient. Breast J. 2002;8(5):286-9.

- Grotto I, Browner-Elhanan K, Mimouni D, Varsano I, Cohen HA,Mimouni M. Occurrence of Supernumerary Nipples in Childrenwith Kidney and Urinary Tract Malformations. Pediatr Dermatol.2001;

- (4):291-4.18 Aydogan F, Baghaki S, Celic V, Kocael A, Gokcal F, et al. SurgicalTreatment of Axillary Accessory Breasts. Am Surg. 2010;76(3):270-2.

- Sadove AM, van Aalst JA. Congenital and acquired pediatric breastanomalies: a review of 20 years’ experience. Plast Reconstr Surg.2005;115(4):1039-50.

- Lesavoy MA, Gomez-Garcia A, Nejdl R, Yospur G, Syiau TJ, Chang P.Axillary breast tissue: clinical presentation and surgical treatment. AnnPlast Surg. 1996;36(6):661-2.

- Fan J. Removal of accessory breasts: a novel tumescent liposuctionapproach. Aethetic Plast Surg. 2009;33(6):809-13.

- Bartsich SA, Ofodile FA. Accessory breast tissue in the axilla:classification and treatment. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;128(1):35-6.

Leave a Reply