How to recognise perinatal mood and anxiety disorders and the effect they have on families.

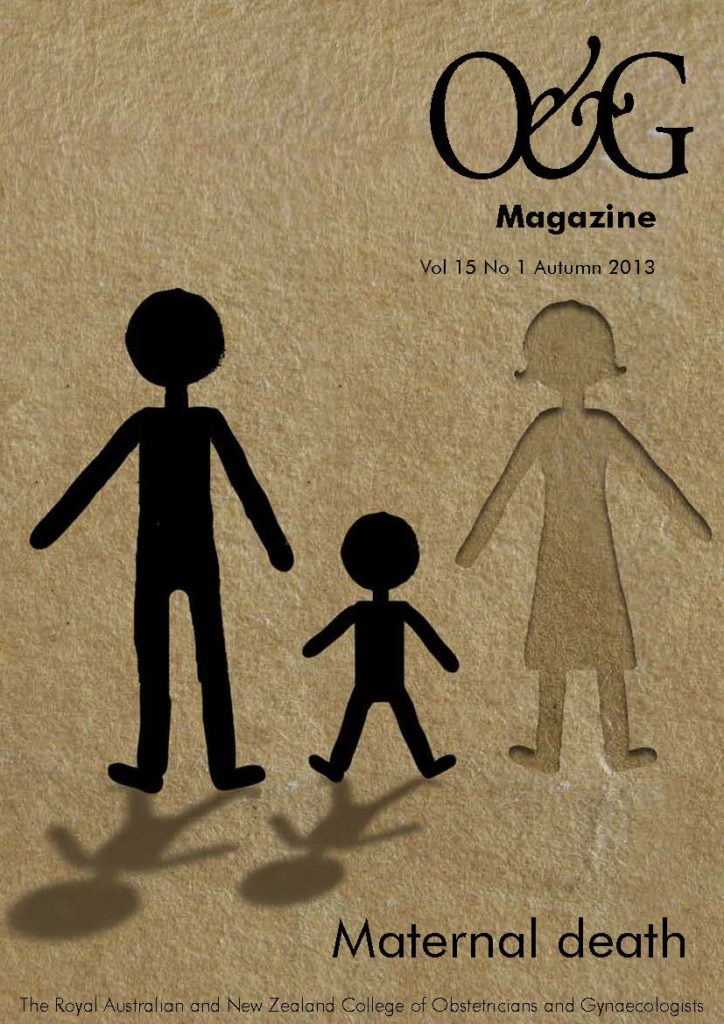

When we consider the maternal mortality rate, it is important to recognise that mental health issues, such as perinatal mood and anxiety disorders, are one of the most preventable causes of maternal (and infant) mortality.

Risks are not just limited to suicide or infanticide (which are both thankfully rare). Perinatal mental health disorders not only impose a huge burden on mothers, their health and parenting capacity, but may also affect infant development and the social and emotional well-being of the entire family.

Psychiatric conditions in the perinatal period

Despite the cultural expectation that women should ‘bloom’ in pregnancy, the prevalence of depression and anxiety is about 12 per cent.1 Antenatal depression can lead to poor self-care, even to the extent of self-injuring behaviours. There is also a growing body of evidence that if a mother is stressed or anxious while pregnant, the child is substantially more likely to be anxious, to have cognitive problems and language delay, and to face an increased risk of attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder, regardless of postnatal anxiety or depression.2 This is thought to relate to increased fetal exposure to cortisol in utero. Conditions such as hyperemesis gravidarum are more common in women with anxiety and depression.3 Antenatal depression is one of the strongest predictors of postnatal depression and it does not often spontaneously remit after childbirth.

Postnatal depression has a general prevalence of 15 per cent.4 Depressive symptoms such as fatigue and poor sleep are hard to disentangle from the normal disruptions of pregnancy and early parenthood. Experiencing pervasive sadness, hopelessness, feelings of inadequacy and guilt, and suicidal thoughts are indicative of mental illness.

Postnatal depression is often referred to as a smiling depression, as it is common for women to have a level of suffering worse that appearances might suggest. Because symptoms may be minimised by the patient, it is important to maintain a high index of suspicion. Diagnostic clues include a decrease in self-care, a ‘wooden’ facial expression and slowed movements, the mother appearing to be excessively anxious about her baby, or unresponsiveness to her increasingly distressed baby.

Postnatal anxiety is as common as depression. The symptoms of anxiety are very distressing and can significantly impact on parenting confidence and the mother-infant relationship. Symptoms include feelings of apprehension and dread, panic; and physical symptoms such as vomiting, bowel upset, tachycardia, hyperventilation, inability to relax, sleeplessness and exhaustion. Obsessional thoughts are intrusive and upsetting, often involving thoughts of the baby being harmed or, more distressingly, unwanted thoughts of the woman harming the baby herself. These conditions need urgent and careful assessment, to distinguish obsessional thoughts (which are seen as abnormal and distressing to the mother) from similar thoughts in depression and psychosis that may be associated with risk to the baby.

Risk factors for perinatal mood and anxiety disorders are varied and include being a very young mother, poverty, stressful life events, grief and loss, domestic violence and low levels of social support, past psychiatric or substance abuse, history of childhood abuse or a perfectionistic personality style. Obstetric factors such as a past history of termination, miscarriage, unwanted pregnancy or a traumatic delivery can also add ‘fuel to the fire’.

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) may have a perinatal prevalence of between two and eight per cent.5 PTSD was first recognised in soldiers involved in horrifying events where they were threatened with serious injury or death. Despite all the advances in safety of obstetrics, difficulties in childbirth can still be very terrifying, traumatic and lead to PTSD. In some cases, the PTSD may be pre-existing. Symptoms include re-experiencing through flashbacks, intrusive memories or nightmares; feeling detached and numbed emotionally; and having intense anxiety responses. PTSD is highly co-morbid with depression, anxiety and substance use. In clinical practice, it can be strongly associated with bonding difficulties. Perinatal PTSD requires specialised psychiatric or psychological treatment.

Puerperal psychosis occurs in one to two per 1000 births, most often a few weeks after childbirth.6 Puerperal psychosis can begin insidiously. The initial symptoms may include quiet confusion, a delirious state, restlessness, excessive anxiety or inability to sleep. Mood symptoms are common, with erratic or inappropriate emotions, manic symptoms of excessive energy and activity, disinhibition, pressured thoughts and speech, loss of contact with reality and hallucinations. Puerperal psychosis is a psychiatric emergency requiring urgent assessment and usually hospitalisation, as the risks of self-harm or harm to the baby are high.

Fathers and family

Postnatal depression may have serious financial implications on the family if the father has to take extra time off work. It can severely affect the marital relationship, in many cases becoming a factor in separations and divorce.

Depression is recognised to affect about five to ten per cent of new fathers.7 It is often hard for men to disclose their symptoms and seek help. Depression may be reflected in an increased risk of substance abuse and domestic violence. Paternal depression may have a detrimental effect on children’s emotional and behavioural development, even after controlling for maternal depression.8

Infant development

Overwhelming research data have shown that infant development occurs in the context of the caregiver relationship. If the caregiver has a mental illness or is severely distressed, it is more difficult for them to see their child’s emotional and physical needs. This may have consequences on the infant’s social, emotional, cognitive and language development.

Depression may impact on mothers’ perception of, and behaviour towards, their infants and children. Depressed mothers can be disengaged, withdrawn and unresponsive to their infants, or they may be overly intrusive. Babies of depressed mothers may have learned to avert their gaze from their mother (while giving other people, such as the clinician, big smiles), or indeed seem depressed themselves. Depressed mothers have told me, ‘my baby doesn’t want me, he won’t look at me’, indicative of their distorted perception of the infant and perpetuating the cycle of avoiding contact and the mother’s low mood.

Unfortunately, and likely as a result of these repeated unsuccessful interactions, children of depressed mothers are more likely to have difficulties in social-emotional, behavioural and cognitive functioning, and are at greater risk for later psychopathology, particularly if the postnatal depression becomes chronic.9

It is important to recognise that postnatal depression is not the only factor impacting on infant outcomes – risks accumulate. They may include: developmental disorders; prematurity or medical illnesses; social adversity, including domestic violence; substance abuse; maternal stressors, such as grief; and relationship difficulties. However, when a mother is thriving and not depressed, she is more able to buffer these risks.

Suicide and infanticide

Having a baby does not protect against suicide. Although the rate is low, suicide is one of the most common and preventable causes of maternal mortality in Australia, the UK and New Zealand.10,11,12 Owing to data-collection issues, suicide is likely under reported.

The majority of suicides by mothers with young children have occurred by violent means. Many of these women have had a previous documented history of mental illness issues. These are generally not just a cry for help, but a determined effort to die.13 Even if unsuccessful, the consequences of an attempted suicide are devastating for the mother and infant.

Intimate partner violence is an associated risk with suicidal ideation and completed suicides worldwide14 and homicide is also a significant cause of maternal mortality.10

Infanticide is also rare, but also likely to be under-reported, meaning research is limited. It appears that maternal neonaticide (murder of a baby in the first 24 hours after birth) is often associated with unwanted pregnancy, pregnancy denial and a young, poorly educated woman, most likely still living at home. Maternal infanticide (defined as murder of an infant less than 12 months old) is more likely associated with mental illness, in particular, psychosis.15

Steps to treatment

The first and most challenging step in treating perinatal mood disorders is recognition. The stigma of mental illness, or concerns about being forced into taking medication, may lead women (or their families) to be reluctant to discuss their difficulties. Depression and anxiety do not spontaneously resolve, indeed they often worsen or become chronic. There are significant risks to women, their families and their infants’ emotional, cognitive and physical development if not treated. These risks need to be considered against the patient’s worries of potentially harming their baby through taking antidepressant medication, or being reluctant to engage in psychological therapy.

It is important to give mental health issues time and space. Asking a patient how they are faring and showing concern about mental health will set expectations that this is an important aspect of obstetric care, and gives permission for discussion and disclosure. The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Rating Scale (EPDS) is a useful self-report screening tool that may help break the ice on this sometimes difficult topic.4 The website www.beyondblue.org.au has a wide variety of patient education-resources on perinatal depression and anxiety.

Delayed bonding and mothers’ feelings of ‘this could be anyone’s baby’ need to be pursued. Infant safety red-flags include violent thoughts, hostility, irritability and parental delusions about the infant, or severe confusion and disorganisation of the unwell mother. The severely depressed or psychotic mother, especially if those delusions involve the child, will need to be hospitalised.

Although the specifics of treatment are beyond the scope of this article, it is important to emphasise that excellent treatment options are available. Pregnancy and breastfeeding are not contraindications to many pharmacological treatments, and psychotherapy and support services are becoming more widely available in each state.

Obstetricians, as trusted experts in physical health and intimate issues, have a tremendous opportunity to open the dialogue regarding mood and stress and reduce the risks to mothers and their families of mental illness.

References

- O’Hara, M, & Swain, A Rates and risk of postpartum depression—A meta-analysis. Int Rev Psych. 1996; 8, 37–54.

- Talge N Neal C Glover V. Early stress, translational research and prevention science network: Fetal and neonatal experience on child and adolescent mental health. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2007; 48

(3-4), 245-61. - Uguz F, Gezginc K, Kayhan F, Cicek E, Kantarci AH. Is hyperemesis gravidarum associated with mood, anxiety and personality disorders: a case-control study. Gen Hosp Psych. 2012;34(4):398–402.

- Buist A, Austin MP, Hayes B, Speelman C, Bilszta JL, Gemmill AW, Brooks J, Ellwood D, Milgrom J. Postnatal mental health of women giving birth in Australia 2002-2004: findings from the beyondblue National Postnatal Depression Program. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2008; Jan;42(1), 66-73.

- Beck C, Gable R, Sakala C, Declercq E. Posttraumatic stress disorder in new mothers: results from a two-stage U.S. national survey. Birth. 2011; 38(3), 216-27.

- Kendell R, Chalmers K, Platz C. Epidemiology of puerperal psychoses. Br J Psychiatry. 1987; 150: 662–73.

- Fletcher, R. The Dad Factor. Finch Publishing, 2011, Warriewood NSW.

- Ramchandani P, Psychogio L. Paternal psychiatric disorders and children’s psychosocial development. Lancet. 2009; Aug 22;374(9690):646-53.

- Grace S, Evindar A, Stewart D. The effect of postpartum depression on child cognitive development and behavior: a review and critical analysis of the literature. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2003; 6(4),263-74.

- Sullivan E, Hall B, King, JF. Maternal deaths in Australia 2003–2005. Maternal deaths series no. 3. Cat. no. PER 42. 2007 Sydney: AIHW National Perinatal Statistics Unit.

- Oates, M. Perinatal psychiatric disorders: a leading cause of maternal morbidity and mortality. Brit Med Bul. 2003; 67: 219–229.

- PMMRC. 2012. Sixth Annual Report of the Perinatal and Maternal Mortality Review Committee. Reporting mortality 2010. Wellington: Health Quality & Safety Commission 2012.

- Austin M, Kildea S, Sullivan E. Maternal mortality and psychiatric morbidity in the perinatal period: challenges and opportunities for prevention in the Australian setting. Med J Aust. 2007; 186 (7): 364- 367.

- Gentile, S. Suicidal mothers. J Inj Violence Res. 2011; 3(2): 90-97.

- Spinelli M. Maternal Infanticide Associated With Mental Illness: Prevention and the Promise of Saved Lives. Am J Psychiatry 2004;161, 1548-1557.

Leave a Reply