How should we manage nausea and vomiting of pregnancy?

Nausea and vomiting of pregnancy (NVP) ranges from the occasional wave of nausea while trying to cook, to severe hyperemesis gravidarum. It affects up to 70 per cent of all pregnancies and persists beyond 20 weeks in 13 per cent. True hyperemesis gravidarum, characterised by severe vomiting, dehydration, significant weight loss and electrolyte disturbance, is relatively rare (0.3–3 per cent).

Women suffering from NVP need a coordinated, evidence-based approach to their illness that recognises the immense toll exacted from being ‘seasick’ for weeks or months on end. By the time these women seek medical attention, they are often physically exhausted, depressed and psychologically distressed by the ambivalence they may feel towards the pregnancy that is causing their illness. Women with recurrent NVP are particularly susceptible if their previous experience of pregnancy was similar. The recurrence risk for hyperemesis gravidarum has been estimated around 70 per cent.

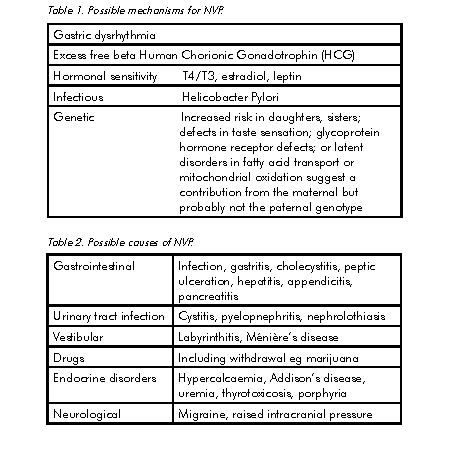

There are many theories for why women experience NVP (see Table 1). HCG receptors are present in area postrema of the brain stem, an area associated with nausea and vomiting reflexes, which is not protected by the blood-brain barrier and freely accessible to HCG. The tendency to recover by either 12 weeks (60 per cent) or 16 weeks (90 per cent) is consistent with the biology of HCG secretion in pregnancy. The association with molar pregnancy and multiple gestations supports this theory.

Apart from the discomfort and misery of NVP, potential maternal complications include hypokalemia, hyponatremia, metabolic alkalosis, gestational hyperthyroxinemia, Mallory-Weiss tear, reflux oesophagitis and the devastating neurological sequelae of Wernicke’s encephalopathy or central pontine myelinolysis.

In women with nausea during pregnancy, the probability of miscarriage is decreased and this is directly linked with the severity of symptoms. There is an increased incidence of preterm delivery and fetal growth restriction limited to women with a poor maternal weight gain during pregnancy suggesting that malnutrition could play a role in these associations.

Investigation

At the first presentation with significant NVP, investigations should include full blood count, urea, electrolytes, creatinine, calcium, liver function tests, thyroid stimulating hormone, urine culture and pelvic ultrasound. This should identify other possible causes of significant nausea and vomiting in pregnancy (see Table 2). The latter is helpful to diagnose molar pregnancy, multiple gestation and to accurately date the pregnancy. During treatment, electrolytes, urinary ketones and liver function tests should continue to be monitored regularly.

NVP and thyroid dysfunction

Biochemical thyrotoxicosis has been reported in up to 60 per cent of women with hyperemesis gravidarum. HCG levels are highest in the first trimester of pregnancy and through cross-reactivity with the Thyroid Stimulating Hormone (TSH) receptor may cause stimulation of the thyroid. The typical finding is a low TSH (<0.5 mIU/l) with or without an elevation of free T4. In most cases, the thyrotoxicosis is asymptomatic but it may cause palpitations, sweating or excessive weight loss. The degree of hyperthyroidism correlates with the severity of vomiting. The course is self limiting and rarely needs specific therapy.

In most cases, the thyroid function tests normalise by 16 weeks, although differentiation from other causes of thyrotoxicosis may not be possible until after pregnancy. Referral for specialist assessment may be considered if the patient has persistent symptoms of thyrotoxicosis or the free T4 is very high, for example, more than 1.5 times the upper limit of the normal range. Occasional patients may experience resolution of their nausea and vomiting following treatment with antithyroid drugs.

Management

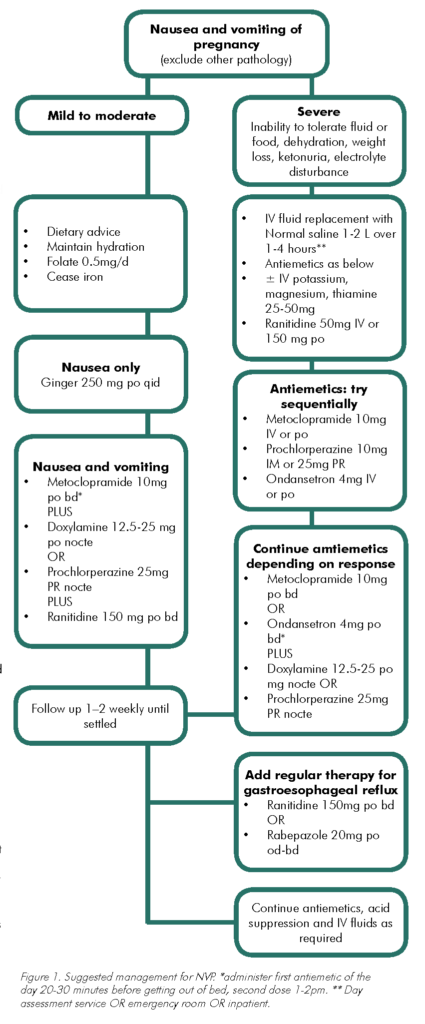

Therapy for NVP should always include sympathetic reassurance and close follow up. A simple algorithm for treatment is described in Figure 1. For mild NVP, dietary modification based on the woman’s own appetite and tastes may be all that is required. Avoiding food preparation and food smells with careful food selection, cold foods or even frozen foods can be helpful. Fluids of any kind should be encouraged, even soft drinks, as these can provide much-needed calories. Pregnancy multivitamins are often poorly tolerated and should be suspended while maintaining adequate intake of folate and Vitamins B1, B6 and B12. Hypnosis and acupuncture may help some women, although they have not been effective in randomised trials.

Where to care for the woman with NVP

The development of Pregnancy Day Stay Units and Early Pregnancy Assessment clinics has allowed a more practical model of care for women affected by NVP. Rather than multiple admissions to hospital or long waits in hospital emergency rooms, a management plan should be developed at first presentation or even preconceptually for women who have previously experienced significant NVP. This should include a staged approach to antiemetic therapy that can commence as soon as symptoms develop.

Antiemetic therapy

A range of antiemetics have been used for NVP, all of which are effective when used in appropriate form and dosage. Extensive studies and/or clinical experience have shown that these agents

have no apparent teratogenic effects and in fact may reduce fetal malformations through their beneficial effects on maternal nutrition. Similarly, there is no evidence that one antiemetic is superior to another and hence drug selection should be based on those drugs with the longest safety record and fewest side-effects.

Pyridoxine (Vitamin B6) and ginger may be helpful for mild nausea in pregnancy, but have little role once vomiting has commenced. Most antiemetics (with the exception of ondansetron) can cause drowsiness. Extrapyramidal side-effects, including agitation and oculogyric crisis, may result from administration of metoclopramide and prochlorperazine. This complication may be dose-related or idiosyncratic. The major adverse effect of ondansetron is constipation. Laxatives, for example, coloxyl 2-4/day should always be given if ondansetron is commenced. As this drug is not PBS listed for NVP, it is also very expensive, although a grateful patient will happily make this investment. The sublingual wafers can be helpful, but absorption still requires the drug to be swallowed as mucosal absorption does not occur.

The timing of antiemetic therapy is critical and should be based on the pattern of the woman’s symptoms, aiming for maximum drug levels when symptoms are worst.

Intravenous fluids and supplements

Women who are severely dehydrated and ketotic need to be carefully assessed and appropriate fluid and electrolyte replacement commenced. Normal saline or Hartmann’s solution are appropriate fluid replacement choices. Dextrose-containing fluids are potentially dangerous and may precipitate Wernicke’s encephalopathy. Hyponatremia requires the infusion of sodium-containing fluids ensuring that hyponatremia is not corrected too rapidly because this can lead to central pontine myelinolysis.

Fluid and electrolyte balance must be reassessed frequently and management modified accordingly. Intravenous vitamins and antiemetics may be co-administered if oral or rectal dosage is not suitable. Continuous subcutaneous infusions of, for example, ondansteron are used in some countries to avoid hospital admission.

Corticosteroids

The use of steroids should be limited to women with intractable NVP. There is still concern that administration of corticosteroids prior to ten weeks gestation may increase the risk of oral clefts. Although cohort studies using corticosteroids for treatment of NVP have been enthusiastic, RCTs have been less convincing. If steroids are used, usual commencement is with either hydrocortisone 100mg IV bd or Prednisone 50mg daily, reducing to the lowest dose that controls symptoms (usually 5–10mg/day) over 7–10 days. This dose may need to be maintained until the natural resolution of NVP.

Additional measures

Once NVP has been present for more than a few weeks, there is inevitably associated gastro-esophageal reflux and inflammation. These women will benefit from aggressive acid suppression with

either an H2 receptor blocker or proton pump inhibitor at high dose. Persistent NVP beyond 16 weeks gestation often reflects undertreatment of this associated problem.

Diazepam and mirtazapine have also been used as adjunctive therapy in some studies. Very occasionally, a woman will fail to respond to these measures. In those cases, admission to hospital

for nasojejunal feeding, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy feeding, total parenteral nutrition or even termination of pregnancy may be required. Early aggressive treatment can usually prevent these sequelae.

Conclusion

The management of NVP is part of the brief of every clinician caring for the pregnant woman. Early aggressive management, including preconceptual planning, is often more effective than trying to rescue a despondent, dehydrated woman requesting termination. Appropriate treatment expectations need to be defined. In general, the aim is to control symptoms to allow adequate oral intake of fluid and food. Complete resolution of nausea and vomiting cannot always be achieved. An important aspect of therapy includes returning a sense of control to the woman and her family, even if her condition is difficult to manage.

Brilliant Article!