Provoked vestibulodynia (formerly known as vulvar vestibulitis syndrome) resulting in entry dyspareunia is the commonest clinical presentation of vulvodynia in young women and unprovoked generalised vulvodynia and clitorodynia are the commonest presentations in post-menopausal women.

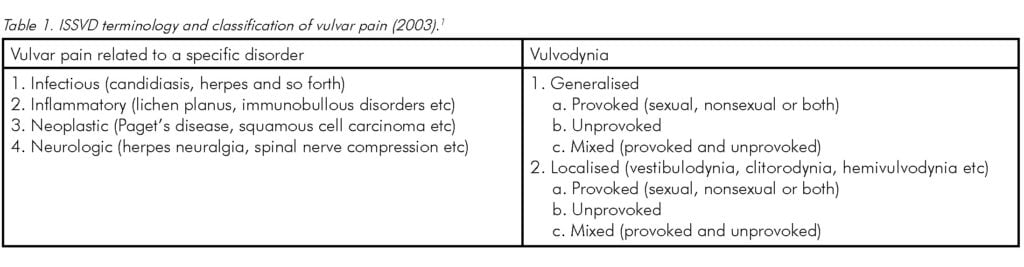

Vulvodynia is a chronic vulvar disorder that is defined by the International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease (ISSVD) as: ‘vulvar discomfort, most often described as burning pain, occurring in the absence of relevant visible findings or a specific, clinically identifiable neurologic disorder.’1 Vulvodynia is classified by whether it is generalised or localised, and whether it is provoked, unprovoked or mixed (see Table 1).

The incidence of provoked vestibulodynia has been reported to be as high as 15 per cent of the female population, although this figure was obtained when patients attending a general gynaecology clinic were assessed purely for pinpoint vulvar tenderness and were not necessarily presenting with dyspareunia.2 The true incidence of significant dyspareunia related to vulvodynia is unknown, but our clinical impression is that it would not be greater than one to two per cent of sexually active females.

For assessment of therapeutic response, Marinoff classified dyspareunia into three grades: grade 1 dyspareunia, preventing intercourse occasionally; grade 2 dyspareunia, preventing intercourse on most occasions; and grade 3: apareunia.3 In a recent study of 150 patients presenting with entry dyspareunia due to provoked vestibulodynia, five per cent were grade 1, 55 per cent were grade 2 and 40 per cent were grade 3.4

Aetiology

The exact pathogenesis of vulvodynia remains unclear and a variety of contributing factors have been suggested, including embryologic abnormalities, genetic or immune factors, hormonal factors, inflammation, infection and neuropathic changes.5

An elegant study comparing the concentration of type C nerve fibres in vestibulectomy specimens from patients with vestibulodynia to perineal skin removed from asymptomatic women during a vaginal repair, showed a significant increase in nerve fibre numbers in those patients with vestibulodynia.6 In the vulvar vestibule, type C fibres are multifunctional, but if they are damaged they revert to their primary function, sensation of pain, whenever any nerve stimulation occurs, however slight. It has been postulated that vulvodynia, and in particular vestibulodynia, may manifest following exposure to trigger factors in these susceptible women. These events may also result in chronic nerve fibre irritation. Proposed trigger factors include recurrent thrush, sexual intercourse without adequate lubrication, sexual trauma and possibly overstretching of the vestibule during vaginal delivery, as patients with vestibulodynia often present following vaginal delivery. In these patients, the tenderness is not related to the episiotomy. In addition, affected women are more likely to demonstrate increased pelvic floor muscle tone on electromyography. This increase in pelvic floor tone is secondary to the hyperalgesia, but it also contributes to nerve hypersensitivity via a dorsal horn reflex pathway.7

Presentation

Generalised unprovoked vulvodynia and clitorodynia can present at any age, but generally occur in middle-aged and elderly women. The pain is typically described as burning, stinging or throbbing, and is often associated with entry dyspareunia. The severity of pain may range from mild to debilitating and may last for hours to days at a time. Symptoms may have been present for a number of years prior to the patient seeking medical advice. Provoked vestibulodynia presents with entry dyspareunia and pain on insertion of tampons. There may have been prior pain-free intercourse and the triggering factor may be an episode of recurrent candidiasis, following sexual assault, following vaginal delivery or just following a single episode of sexual penetration without adequate lubrication.

Evaluation

Vulvodynia can be diagnosed following a careful clinical history and physical examination. A thorough history should include the characteristics of the pain, other symptoms (for example, itch, discharge and so forth), treatment history, trigger factors, sexual history, medical and surgical history, and impact on quality of life. The vulva, vagina and cervix should be carefully inspected to exclude other causes. A cotton swab (cotton-wool bud) test will make the diagnosis of vestibulodynia with tenderness confined purely to the vulvar vestibule. The main tender areas are at the base of the hymen, usually around the openings of the Bartholin’s ducts, and may also extend to the para-urethral glands and subclitorally. Focal erythema is often seen confined to the areas of tenderness. A biopsy is not required to make a diagnosis of vulvodynia and should only be considered if there is a clinical suspicion of other pathology known to cause vulvar pain, for example, lichen planus.

Chronic vulvar candidiasis is often seen in patients with vestibulodynia. It may not be associated with itch or vaginal discharge and vaginal swabs are unreliable. The typical symptoms of chronic candidiasis are a burning sensation in the vulva, with occasional skin splitting. It is often cyclical, becoming worse in the week prior to menses, as well as occurring postcoitally. Diagnosis of chronic candidiasis can be suspected on the clinical history and by vulvoscopy, and confirmed by culture of vulvar skin scrapings.8

Management

The optimal management of vulvodynia requires a multidisciplinary approach. Many patients presenting with vulvodynia (particularly provoked vestibulodynia) have tried multiple treatments, have had multiple diagnoses, often being labelled as having a purely psychosexual disorder and consequently become understandably frustrated. An important part of the management is giving the patient a diagnosis, an explanation of her condition and a plan of management. The patient should also be reassured that any psychological distress she is experiencing is purely secondary to her pain and is not a primary component of vulvodynia itself. The initial approach involves general vulvar care and encouragement in the use of an oil-based lubricant during any sexual activity. Therapeutic interventions include: oral and/or topical medication, physiotherapy, counselling and finally surgery.

Drug therapy

Tricyclic antidepressants, such as amitriptyline, have been used with good response rates of 60–70 per cent.9,10 This is usually given orally, starting at 10mg nocte, and increasing the dose every fortnight until a therapeutic response is achieved or a maximum of 150mg daily is reached. Drowsiness is the commonest side effect and is the main limiting factor. Nortriptyline can be substituted if dryness of the mouth is a problem. Once a therapeutic dose is achieved, therapy is continued for six months and then slowly reduced. If symptoms reoccur, another six months of therapy is given and only rarely does a patient require a third course. Anticonvulsants, such as carbamazepine, have been used as second-line agents with limited success10 and gabapentin has been moderately effective,11 although the cost can be prohibitive.

Recently, a topical cream containing amitriptyline two per cent with baclofen (a neuromuscular blocking agent) was reported to have a 71 per cent success rate, although this was only a small study.12 In a much larger study at the Royal Women’s Hospital, Melbourne, using a topical cream with just amitriptyline two per cent alone, we had a success rate of 56 per cent.4 At present, we are evaluating a topical amitriptyline five per cent ointment with encouraging initial results. Using topical amitriptyline is an excellent way of introducing the patient to the concept of using an antidepressant drug for another purpose and hence removing any stigma associated with it. Interestingly, the topical agent has worked in a significant number of patients who failed to respond to the oral drug. Thus we are now using topical amitriptyline therapy as our first-line treatment. Topical xylocaine ointments should be avoided if possible because of the risk of trauma and laceration if the vulva is completely numb.

Botox injections have been hypothesised to reduce the hyper-tonicity of the pelvic floor muscles and peripheral neuropathy. However, problems with unpredictable anal incontinence have limited their use.13

Physiotherapy

Physiotherapy is an integral component in the management of vulvodynia. The aim is to re-train the pelvic floor muscles so that the resting muscle tone is reduced. This can be achieved by pelvic floor muscle exercises, manual therapy (for example, touch de-sensitisation, local massage, trigger point therapy), use of vaginal dilators and combination treatment using electromyographic biofeedback.14

Psychological

One RCT has shown that cognitive behavioural therapy is associated with a 30 per cent decrease in reported vulvar pain with intercourse.15 When compared to biofeedback and surgery, all three groups demonstrated equally significant improvement in psychosexual functioning. As a result of any chronic pain, interpersonal and individual psychological difficulties may develop. Sexual, individual and marital counselling should also be considered in patients with ongoing difficulties in these areas.

Surgery

Surgical treatment for vulvodynia has greatly improved over the past 25 years since Woodruff and Pamley initially described perineoplasty for vestibular pain.16 It is usually reserved for patients with localised vestibulodynia where conservative management has failed. A surgical vestibulectomy removes the hypersensitive portion of the vestibule and is performed under general anesthetic. The procedure typically consists of excising a horseshoe-shaped area of vestibular skin from the two to ten o’clock position with the proximal incision just in the vagina above the hymen so that the minor vestibular glands at the base of the hymen are completely removed. The width of skin excised is determined by the extent of the tenderness (usually 1–2cm) and then the posterior vaginal wall is mobilised by sharp dissection and advanced to cover the defect. Additionally, the para-urethral and subclitoral minor vestibular glands can be excised by separate incisions. In a retrospective study, over 80 per cent of patients reported that they would recommend the procedure as an effective treatment.17

Conclusion

Vulvodynia is a chronic condition that causes vulvar discomfort in the absence of any clinically identifiable neurological disorder. A thorough clinical assessment, recognition of the emotional

and sexual implications, and knowledge of the treatment options available can lead to effective management for the patient. Treatment should be performed in a multidisciplinary setting. A wide range of therapeutic interventions are available with variable efficacy. Systematic, randomised controlled trials are required to evaluate the efficacy of the current therapeutic options.

References

- Moyal-Barracco M, Lynch PJ. 2003 ISSVD terminology and classification of vulvodynia: a historical perspective. J Reprod Med 2004;49:772.

- Goetsch MF. Vulvar vestibulitis: prevalence and historic features in

a general gynecologic practice population. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1991;164:1609–14. - Marinoff SC, Turner ML. Vulvar Vestibulitis Syndrome: An overview. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1991; 165: 1228–33.

- Pagano R, Wong S. J Low Gen Tract Dis. 2011; In print.

- Damsted-Peterson C, Boyer S, Pukall C. Current perspectives in vulvodynia. Women’s Health 2009;5.4:423.

- Bohm-Starke N, Hilliges M, Falconer C, Rylander E. Increased Intraepithelial Innervation in Women with Vulvar Vestibulitis Syndrome. Gynecol Obstet Invest 1998;46:256–60.

- Glazer HI, Jantos M, Hartmann EH, Swencionis C. Electromyographic comparisons of the pelvic floor in women with dysesthetic vulvodynia and asymptomatic women. J Reprod Med 1998;43:959–62.

- Pagano R. The Value of Colposcopy in the Diagnosis of Candidiasis in Patients with Vulvodynia. J Reprod Med. 2007;52 (1):31–34.

- Nyirjesy P, Halpern M. Medical management of vulvar vestibulitis: results of a sequential treatment plan. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol 1996;3:193–97.

- Pagano R. Vulvar vestibulitis syndrome: an often unrecognized cause of dyspareunia. ANZJOG 1999;39:79–83.

- Ben-David B, Friedman M. Gabapentin therapy for vulvodynia. Anasth Analg 1999;89:1459–60.

- Nyirjesy P, Lev-Sagie A, Mathew L, Culhane J. Topical Amitriptyline-Baclofen Cream for the treatment of Provoked Vestibulodynia. J Low Gen Tract Dis 2009;13:4:230–36.

- Vancaillie Thierry. 2011 Personal communication.

- Glazer HI, Rodke G, Swencionis C, Hertz R, Young AW. Tratment of vulvar vestibulitis syndrome with electromyographic biofeedback of pelvic floor musculature. J Reprod Med 1995;40:283–90.

- Bergeron S, Binik YM, Khalife S, Pagidas K, Glazer HI, et al. A randomized comparison of group cognitive-behavioral therapy, surface electromyographic biofeedback, and vestibulectomy in the treatment of dyspareunia resulting from vulvar vestibulitis. Pain 2001;91:297–306.

- Woodruff JD, Parmley TH. Infection of the minor vestibular gland. Obstet. Gynecol 1983; 62:609–12.

- Eva LJ, Narain S, Orakwue CO, Luesley DM. Is modified vestibulectomy for localized provoked Vestibulodynia an effective long-term treatment? A follow-up study. J Reprod Med 2008;53:435–40.

Leave a Reply