New Zealand supports homebirth, but assessments of the associated benefits and drawbacks differ according to the individual’s experience.

Homebirth appeals to those women who feel that the benefits for their family and themselves outweigh the risks of adverse events. A woman’s perception of risk will be individual and her views on what constitutes significant risk will vary with circumstance, culture and clarity of understanding the issues. The likelihood of potentially serious events during a homebirth involving a screened low-risk woman is no greater than for those planning to deliver in hospital. However, it is the proximity of support in a hospital setting for such events that can make the difference.

A planned homebirth for a low-risk, well-informed woman, should be differentiated from an unplanned homebirth where antenatal care and circumstances may be suboptimal. Similarly, water birth is also a completely different topic not addressed here. In this article we will look at the screening, the safety and the incidence of homebirth in rural and urban areas of Southern New Zealand and also explore the different viewpoints of those involved.

In contrast to RANZCOG’s current statement on homebirth, the recent Royal College Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) report recommends homebirth in the UK, in particular circumstances, for those women who are screened as low risk. The RCOG and Royal College of Midwives joint statement3 supports homebirth for ‘women with uncomplicated pregnancies who are at low risk of complications’. It also states that homebirth may confer considerable benefits for women and their families. Overall, the benefits of homebirth include: reduced experience of pain; family bonding; participation by children and family; cultural aspects; and avoidance of travel in labour. The ability to perform culturally traditional care, such as massage, in labour is important to some. The recommendations state an experienced midwife should be present, who has regularly updated skills from appropriate workshops in emergency obstetric procedures and neonatal resuscitation.

In the UK, the incidence of homebirth is around three per cent, whereas in Scandinavia and the Netherlands it exceeds 30 per cent. In New Zealand, the homebirth rate is seven per cent, and appears to be increasing, while in Australia it is static at 0.2 per cent. We can usefully explore the reasons for these differing approaches. It may be that New Zealand, with its smaller size and experienced midwifery population, is closer to the UK and Dutch model of care than that of Australia. However, geographical distances, weather and time delays in transfer do impact on the delivery of care.

There is unlikely to be a randomised study regarding the safety of homebirth, but large cohort studies can give reasonable evidence, such as a large retrospective cohort study from Holland involving 0.5 million births in primary care over a six-year period. The neonatal outcomes (NICU admission or mortality) for this group were identical to those with planned hospital births. Babies of those delivering at home were equally likely to be admitted to NICU as hospital planned births. Adverse neonatal outcomes in first 24 hours and first week of life were the same for each group: 7/1000. In the Netherlands, the relatively high incidence of homebirth necessitates efficient infrastructure and transfer services: 40 per cent of primipara and 14 per cent multipara require transfer during labour. The outcomes were found to be less favourable for primiparous and non-Dutch women and for those women over 35 or under 25 years old. While primipara experienced more transfers, multipara who had previously delivered two or more children and were on average 41 weeks gestation had the least incidence of transfer. Despite this evidence, Sturdee concludes that while this study’s findings were significant, its context was in a totally different practice environment and geographical area to Australia.

Safety of homebirth in England is currently being assessed and the ‘Birthplace study’ results are soon to be published. Safety considerations are not only physical, but also include emotional and psychological wellbeing.

Safety and transfer issues

Up until 60 years ago, 60 per cent of births were at home, as there were few alternatives available to most women. In 1950s New Zealand, a public program of building maternity and surgical facilities, alongside a new National Health System, gave all women equal access to maternity care, even in rural areas. Antibiotics, progress in anaesthesia and neonatal knowledge as well as nutrition also added to the improved pregnancy outcomes from 1950s onwards. However, there remain women who choose to have only essential medical interventions. Where there is minimal risk to mother and child, midwifery primary care or homebirth can be appropriate. In 2011, women settling in the resort towns of Otago have no secondary hospital facility, however, nine primary care facilities exist in the Southern Region, and altogether deliver more than 400 babies each year, with an additional estimated 150 homebirths. Such maternity facilities are supported by emergency transfer to appropriate base hospitals. The current increasing birth rate in these areas necessitates appropriate future-proofing, with outreach secondary care clinics and facilities from the base hospitals. Some low-risk women still prefer to travel to the base hospital during labour or, if high risk, will relocate near the main centre prior to the delivery date.

By definition ‘rural’ in New Zealand is more than one hour’s travel (approximately 80km by road) from the base hospital. In the Southern Region, three to four hours’ road travel is common. This may become six hours, with changes in ambulance and voluntary drivers necessary en route. In adverse weather a transfer can take even longer in any season and there are no all-weather helicopters. Furthermore, in New Zealand the local ambulance is not used for maternity cases alone. Competing needs of trauma, acute medical and surgical cases must also be met by the same service.

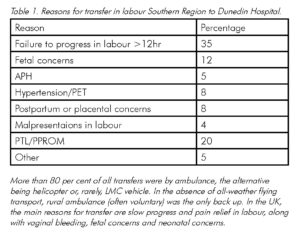

Within New Zealand, the Otago and Southland need for transfer data parallels that in the UK, but in rural areas there are the additional risks of transfer time and complications. An Otago study of ‘investigated transfers to the region’s tertiary unit over a five-year period in the Southern Region’ looked at this. The reasons for transfer from primary care and outcomes were assessed in the context a total of 20 000 births; of these, 415 transfers from rural primary units to tertiary centre were identified. The most frequent reason was failure to progress in labour (30 per cent) of which half subsequently required delivery by caesarean section.

How can homebirth be made safer?

RCOG recommends that midwives have a colleague at delivery and undergo regular training in the emergency events that may be faced. Telephone contact at the home and normal standards of

care in labour, preferably with partograms, are stressed. Likewise, routine fetal heart assessment and active management of the third stage are expected to ensure normal labour and fetal wellbeing. The infrastructure for transfer to allow this to occur in a timely and safe manner, in all weathers, is essential.

A primary unit midwife’s viewpoint

‘Our midwifery practice continuously strives to promote birth as a normal life event. We are conservative in our approach to place of birth, whether it is at home or in the primary unit. We factor in to the woman’s care plan, our resources, the season and weather, midwifery support and adhere to Ministry of Health Guidelines.7 Most women are self-directive and well informed about their care. They feel able to exercise choice regarding the place of birth.’

A woman’s viewpoint

Tuakana Tollich’s decision-making process was typical of those who choose home care by a midwife. A 36-year-old Maori woman who recently delivered her fifth child in rural Central Otago, Tuakana knew about the birthing options available to her through her midwife. She lives close to a primary unit, but two hours from a secondary centre. For her fifth pregnancy she chose a homebirth. Tuakana has had a range of birth experiences. For her, the choice of homebirth was mostly about the family being able to be part of the process and in familiar surroundings. Avoiding travel with young children was also important, so there was less family disruption.

Tuakana’s first two births were normal, the first in hospital and the second at home. The next pregnancy required an operative delivery from a baby diagnosed with a congenital hydrops. After this Tuakana had a successful homebirth, this time in a rural setting, and was uneventful.

The most recent birth was planned as a homebirth. However, progress in this post-term labour was slow, so transfer to the local primary centre was arranged where a spontaneous vaginal delivery was achieved without intervention, allowing her and family to be home again together the same night.

The benefits of family support and involvement were the important issues for her, rather than cultural issues. Tuakana says she felt safe throughout the process, because of the support and open discussion of risk management by her midwife and support team.

A lead maternity carer’s viewpoint

Mary Richie is a Dunedin-based lead maternity carer (LMC) who supports homebirths, but with clear criteria. She suggests the screening checklist for women suitable for homebirth should include the following:

- A normal obstetric history.

- A previous normal birth.

- A normal pregnancy.

- An understanding of what homebirth entails, including restricted pain-relief options.

- A willingness to transfer should a complication arise for mother or newborn and understanding of potential unpredictable risks.

- A mobile or land line telephone connection, support of another midwife and transport.

- An understanding of the need for the woman and partner to undertake the responsibility for the homebirth and inherent risk however minimised.

- A willingness to accept assessment of fetal wellbeing and progress in labour. Physiological management of third stage of labour, unless there were risk factors or heavy bleeding. (As unexpected post-partum haemorrhage (PPH) can occur, Mary carries syntocinon and syntometrine, IV equipment and fluids.

- A restriction of care to those living within a 30-minute travel radius from the hospital.

Mary attends a handful of births at home each year with good outcomes. Over the last ten years her transfers have been few and chiefly for pain relief. She reports the women note several benefits: greater comfort in their own surroundings; less pain; family participation in the birth of a new family member; their own bed and avoidance of travel.

A specialist’s viewpoint

The obstetrician’s view will inevitably be coloured by experience of an incident or near misses whether women were low risk or not. They will be less aware of the normal homebirth outcomes.The Dunedin Unit receives transfers from a wide hinterland, where the significant majority of midwives are practising within safe guidelines suggested above. Nevertheless, transfers from home have included the range of intrapartum obstetric emergencies that can occur, including cord prolapse with membrane rupture in early labour, transverse lie with arm presentation and preterm breech. Haemorrhage has associated with atony, retained placenta, trauma, antepartum placental problems and uterine rupture. While the outcomes are good for most of these acute complications, it is important that appropriate audit and discussion follow such transfers. This ensures maximal learning from these events for both individuals and care systems.

Women’s perception of risk is inevitably different to that of their medical carers, who from time to time see avoidable maternal morbidity and adverse fetal outcomes. Education of women, adequate numbers of skilled midwives who are regularly updated in obstetric emergency drills, a smooth interface for communication and transfer to secondary care, and transport services are the essential prerequisites before homebirth can approach the safety of hospital birth or quality of outcome achieved in some European countries. Rurality poses additional risks that are hard to convey to the low-risk woman. Overall, this specialist will always advise safety over convenience. I may not understand why some women choose homebirth. Similarly they might not understand why I would not. The reason is very clear to me: with my obstetric history, I simply would not be alive to tell the tale.

References

References are available from the author upon request.

Leave a Reply