Rheumatic heart disease has been all but forgotten in mainstream Australia. However, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, particularly those living in regional and remote Australia, have among the highest rates of the disease in the world. This burden is disproportionately borne by women.

Rheumatic heart disease (RHD) is a consequence of an earlier group A streptococcal infection and associated acute rheumatic fever (ARF). In Australia, RHD is particularly seen in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.1 However, with immigration from areas with a higher risk of RHD (Africa, South America and Asia2), it can also be seen in young, non-Indigenous Australians. Generally, the onset of RHD occurs in childhood and adolescence; it affects more women than men. It can often be first detected in women of childbearing age and can potentially complicate pregnancy and labour. While the presence of RHD rarely means women cannot become pregnant, there are a number of factors that are important in ensuring a good outcome for both mother and child (see box below).

Important factors in the early detection and management of RHD in women who are planning to become pregnant or who are pregnant

- Detect early and exclude RHD

a. In populations at high risk of RHD, all women who have a heart murmur require an early echocardiogram.

b. If there is a history of ARF, the result of a recent echocardiogram should be reviewed. - Assess and treat before pregnancy

a. Refer anyone with RHD for specialist physician/cardiologist review.

b. Discuss fertility planning and contraception with women with RHD.

c. Ensure fertility planning informs discussions regarding management in all women in whom surgery is planned. - Ensure a coordinated and multidisciplinary care team is in place early – pregnant women with RHD require a team approach linking primary healthcare, obstetric services, anaesthetics and specialist physicians/cardiologists.

What is it?

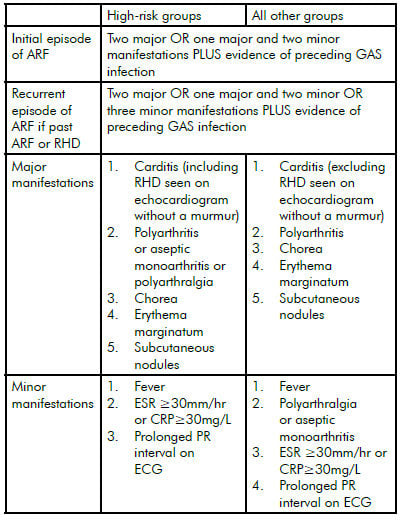

ARF is a non-infective response of a person’s immune system to an earlier throat infection with a common bacterium, group A streptococcus (GAS).3 It has also been suggested that skin infection with GAS may cause ARF though the evidence for this is less clear.4 The signs and symptoms of ARF include painful, stiff and swollen joints, fever, skin rash and heart and brain inflammation. In Australia, ARF is diagnosed on the basis of a number of criteria, including: clinical signs and symptoms and the findings of ECG, echocardiography, throat swab and blood tests (see Table 1).

Table 1 Australian criteria for the diagnosis of ARF (see Diagnosis and management of acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease in Australia: An evidence-based review5 for more details)

Rheumatic heart disease results from the cumulative effects of ARF-induced heart inflammation (carditis). It is a chronic heart condition associated with thickening and scarring of heart valves. This damage can affect the function of valves (particularly the mitral and aortic valves) leading to leaking (regurgitation) or blockage (stenosis). More severe RHD can result in tiredness, shortness of breath, heart failure, infection of the heart valves (endocarditis)6 and stroke.2 During pregnancy, additional blood volume and workload on the heart can worsen many of these problems. In more severe RHD, surgery may be required to replace damaged valves with bioprosthetic (tissue valves derived from animals or humans) or mechanical valves, with the latter requiring lifelong anticoagulation (warfarin) to prevent clotting. In selected patients it may be possible to repair rather than replace valves at surgery or even open a stenosed mitral valve using less invasive percutaneous balloon mitral valvuloplasty.

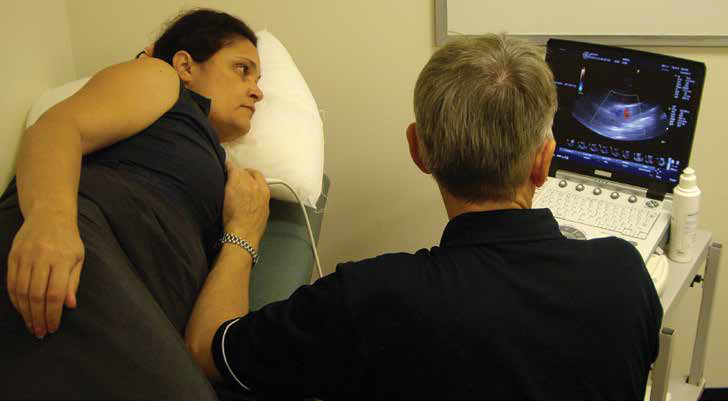

Echocardiography is an essential tool in the diagnosis, assessment of severity and management of RHD. Like obstetric ultrasound, it is non-invasive and, with the development of smaller and portable echocardiography machines, it is now possible to provide local echocardiography services even to people living in very remote communities. This requires investment in suitable equipment and resourcing to ensure that there are mobile outreach echocardiography technicians or that staff providing visiting specialist outreach services have the requisite skill to perform echocardiography.

Epidemiology

The international incidence of ARF is almost 500 000 per year and 60 per cent of these cases will develop RHD each year. The prevalence of RHD is believed to be at least 15.6 million cases, with 282 000 new cases and 233 000 deaths each year.2

While there has been a decrease in the incidence and prevalence of ARF and RHD in industrialised countries during the past 50–100 years, these diseases remain major public-health concerns in developing countries. However, there are some population groups in developed countries that remain at risk. This is the case within Australia, where the acquisition of ARF and RHD is almost exclusively restricted to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations, particularly those living in rural and remote central and northern Australia. In these populations, the burden of ARF and RHD is among the highest in the world. The annual incidence of ARF in Aboriginal people in the Northern Territory has been reported as 250–350 per 100 000 per year in the 4–15 age group, and the prevalence of RHD between 1.3 and 1.7 per cent (all ages).1 Similar levels of disease have been reported in northern Queensland and the Kimberley in the far north of Western Australia. By contrast, ARF in now rare in other Australian populations groups and the relatively small number of RHD cases seen in these groups occur mostly among the elderly and people born in Asia, Africa and South America who have subsequently migrated to Australia.

Management and antibiotic prophylaxis

In Australia, a guideline for the diagnosis and management of ARF/RHD has been published by the National Heart Foundation of Australia and the Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand.5 This guideline has been adapted for local use by jurisdictions to reflect local healthcare systems.7–9 While the long-term priority for addressing ARF and RHD remains identifying effective targets for primary prevention, the current priority remains the secondary prevention of GAS infection with prophylactic antibiotics in those with a history of ARF or known RHD. The most effective form of secondary antibiotic prophylaxis is intramuscular benzathine penicillin, usually on a monthly (but ideally on a three-weekly) basis. This aims to prevent further attacks of ARF that could lead to the development of RHD in those with normal heart valves or worsen valve damage in those with the earliest changes of RHD.

Figure 1. Echocardiography is both portable and accessible.

RHD and women

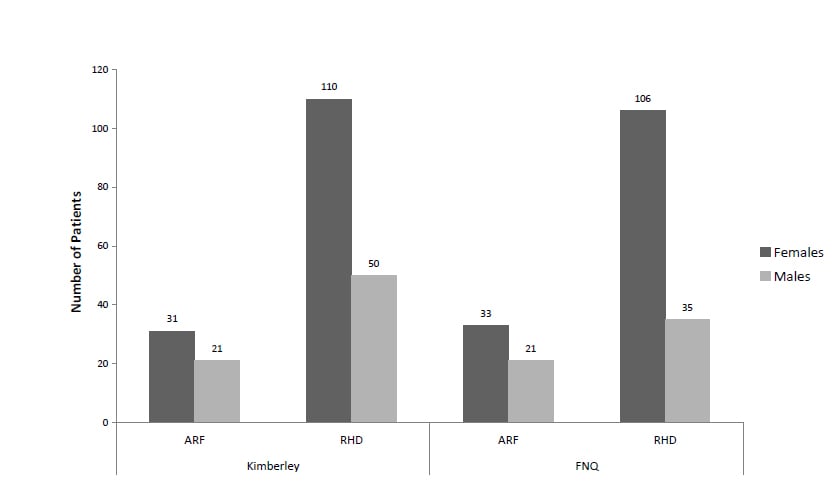

Women are at higher risk of developing RHD compared with men, despite similar rates of ARF. A prospective surveillance program of ARF and RHD in Fiji between 2005 and 2007 revealed that the relative risk of admission for RHD for females compared with males was 2.5 (95 per cent CI, 1.6–3.8).10 A recent audit of the management of ARF and RHD, in the Kimberley region of Western Australia and Far North Queensland revealed a similar disparity in disease (see Figure 2). Of the 301 people with RHD 216 (71.8 per cent, 95 per cent CI 66.3–76.8) were women. Overall, the odds of having RHD in women was 2.2 (95 per cent CI 1.6–3.1) compared with men.

The reasons for this far greater risk of RHD in women remain poorly understood. While it may be explained by a greater exposure to GAS in women caring for children, this would fail to explain the lack of a similar gender disparity in ARF incidence in younger people. It may also be, at least in part, attributable to women having a greater opportunity for diagnosis of RHD by accessing healthcare more frequently than men or a gender-related predisposition to autoimmune disease.11

Figure 2. Over-representation of women with RHD in the Kimberley (Western Australia) and Far North Queensland.

RHD in pregnancy

Pregnancy places an increased demand on the heart even in otherwise well women. Changes associated with pregnancy include an increase in blood volume and heart rate, a reduction in the resistance of the arterial circulation and an associated increase in cardiac output. These normal changes tend to worsen pre-existing heart valve problems, including those associated with RHD. For this reason it is not uncommon that rheumatic heart disease can sometimes be first diagnosed in pregnancy through finding a heart murmur or the onset of heart failure. Unexplained shortness of breath in pregnancy and during and after delivery in patients at risk of RHD should always raise the suspicion of RHD and heart failure.

The National Heart Foundation of Australia and Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand’s Diagnosis and management of acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease in Australia: an evidence-based review5 highlights five maternal risk factors associated with RHD during pregnancy. These are:

- Reduced left ventricular function.

- Significant aortic or mitral stenosis.

- Moderate or severe pulmonary hypertension.

- A history of heart failure.

- Symptomatic valvular disease before pregnancy.

Health providers caring for pregnant women with RHD should refer to these guidelines for detailed advice (see box below). In general, regurgitant valve lesions are much better tolerated in pregnancy compared with stenotic lesions. Mitral and aortic stenosis should therefore raise particular concern. The importance of identifying RHD in women before they become pregnant is reinforced by the high risk of fetal loss associated with valve surgery during pregnancy. The key to RHD management in pregnancy remains early and regular monitoring by a multidisciplinary team. Management of labour and delivery in women with RHD and mechanical valves is complicated and is outlined in the review by Sartain.12

Specific recommendations for management of RHD and prosthetic heart valves in pregnancy

- Mitral regurgitation: generally tolerated well during pregnancy. Heart failure may require diuretics and vasodilators

(hydralazine, nitrates, dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers). Vaginal delivery is usually possible when heart failure is controlled. - Mitral stenosis: if moderate or severe often causes heart failure. If symptoms are not severe, medical therapy with diuretics, digoxin and/or beta-blockers to slow heart rate is indicated. If symptoms remain there is significant risk to both mother and fetus and relief of mitral stenosis is usually required. Percutaneous balloon valvuloplasy is preferred given the high risk of fetal loss with surgery. Vaginal delivery is the usual approach although caesarian section should be considered in cases of severe disease with severe pulmonary hypertension.

- Aortic stenosis: if mild or moderate can usually be safely followed during pregnancy. Severe disease involves significant risk of adverse outcomes and percutaneous balloon aortic valvuloplasty may be required.

- Prosthetic heart valves: choice of valve prosthesis in the childbearing age group is complicated by the fact that while tissue valves have the advantage of not requiring anticoagulation most will require later replacement. Most patients with prosthetic valves and few symptoms tolerate pregnancy well.

- Mechanical prosthetic valves and anticoagulation: mechanical valves are a high-risk group as all anticoagulation options pose maternal and/or fetal risks. Patients taking warfarin need early counselling and specialist advice before becoming pregnant. Women on warfarin who can become pregnant require reliable contraception.

See Diagnosis and management of acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease in Australia: An evidence-based review5 for more details.

Conclusion

The normal cardiovascular changes associated with pregnancy exacerbate problems associated with pre-existing RHD and pregnant women with RHD must be managed according to the severity of their valve lesion and symptoms. Women with mechanical prosthetic valves who require anticoagulation are particularly at risk. The key to rheumatic heart disease management in pregnancy is detection and management before women become pregnant and early and regular multidisciplinary care in pregnancy, including primary healthcare providers, obstetricians, anaesthetists and specialist physicians/cardiologists. If managed early and proactively most women with RHD can become pregnant with a positive outcome for mother and child.

References

- AIHW: Field B. Rheumatic heart disease: All but forgotten except among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Canberra: Bulletin no. 16. AIHW Cat. No. AUS 48. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; 2004. Report No.: Bulletin no. 16. AIHW Cat. No. AUS 48.

- Carapetis JR, Steer AC, Mulholland EK, Weber M. The global burden of group A streptococcal diseases. Lancet Infect Dis 2005; 5: 685–94.

- Wannamaker LW. The chain that links the heart to the throat. Circulation 1973; 48: 9–18.

- McDonald M, Currie BJ, Carapetis JR. Acute rheumatic fever: A chink in the chain that links the heart to the throat? Lancet Infect Dis 2004; 4: 240–5.

- National Heart Foundation of Australia (RF/RHD guideline development working group) and the Cardiac Society of

- Australia and New Zealand. Diagnosis and management of acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease in Australia – an evidence-based review; 2006.

- Rémond M, Baskerville C, Hanrahan B, Burke A, Holwell A, Maguire G. Infective endocarditis and rheumatic heart disease. CSANZ 2nd Indigenous Cardiovascular Health Conference – Final Program and Abstracts 2011: 29.

- Queensland Health and the Royal Flying Doctor Service (Queensland Section). Chronic disease guidelines, 2nd edition. Cairns 2007. Kimberley Aboriginal Medical Services Council (KAMSC) and WA Country Health Service (WACHS)

- Kimberley. Kimberley chronic disease therapeutic protocols. 2007 [cited; Available from: http://www.kamsc.org.au/content/resources/resourceguidelines.html . Centre for Remote Health. Carpa standard treatment manual. 5th ed. Alice Springs: Central Australian Rural Practitioners Association 2010.

- Steer AC, Kado J, Jenney AW, Batzloff M, Waqatakirewa L, Mulholland EK et al. Acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease in Fiji: Prospective surveillance, 2005–2007. Med J Aust 2009; 190: 133–5.

- Oliver JE, Silman AJ. Why are women predisposed to autoimmune rheumatic diseases? Arthritis Res Ther 2009; 11: 252.

- Sartain J. Obstetric patients with rheumatic heart disease. O&G Magazine 2008; 10: 18–20.

Leave a Reply