Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men have an important role to play in the improvement of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women’s health.

The role of the man was held in high esteem. He performed ceremonial rites and guided the young boys through their initiation into manhood. We guided our young men to understand their world, to know their country, to make their tools, to dance and paint, to learn our stories, to know the spiritual world. Traditionally, Noongar men were providers for their families, they were at one with the land that provided them with life and, most importantly, great inner strength and spirituality.

– Noongar (Western Australia) Men’s Manual

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males are fathers, partners, uncles, brothers, nephews, grandchildren and sons. All of these identities play significant roles in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women’s lives and are intimately related to women’s social and emotional wellbeing, both socially and culturally, at individual, family and community level. The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander gender constructs are traditionally quite different from modern western constructs. These gender constructs had always been complementary, with survival in some of the harshest country in the world dependent on the effectiveness of these complementary roles.

Although, historically, in the dormitory system at many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander missions, the father was excluded from the parenting role, there is opportunity to re-colonise this area and ensure the inclusion of men. This doesn’t necessarily cut across men’s and women’s business culture lore, but it does need to be done sensitively and in partnership with both local men’s and women’s groups.

There are numerous cultural traditions around the nurturing of children where the role of the father is important. Brian McCoy, in his book on the western desert Aboriginal men, describes this in the context of ‘Kanyirninpa’, which can be described as ‘holding’ or nurturing, especially in the context of older men nurturing and caring for younger males.1 This is a central part of traditional Aboriginal culture in this region and dynamically connects nurturance, relatedness, authority, and autonomy, together with family, land and Dreaming in the context of Aboriginal men. The ability of our programs to be able to understand and acknowledge these cultural principals, if not work within them, is central to their success in resonating with men in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities.

In many areas, the uncle/nephew relationship was responsible for the teaching, training and discipline, and many still practice this way, though some need to be re-connected culturally to this process. With this understanding, it is imperative that some of the root causes of problems such as violence, dysfunctional relationships and poor parenting are addressed with males, as well as responding to the consequences of dysfunction for women and children.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men have been very proactive in attempting to address their own issues, but at community level lack capacity, resources and real support to do this, even though Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men’s groups have developed in almost every Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community across Australia.

Political context

In the context of the Northern Territory Emergency Response (NTER), initiated in 2007 and still in place, support for programs to improve men’s health and wellbeing and to address community violence with males was not politically expedient, as there was a media-driven stereotyped view of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males (drunken, welfare dependant, wife bashing, child abusers) that was a political disincentive.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males were not invited to the then Federal Minister Brough’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Domestic Violence Summit and the ‘Framework for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Male Health’2 developed by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males was shelved by the Federal Health Department as not being a priority.

The new National Male Health Policy has now picked up this important policy document, and newer Australian Government funding for programs for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men as fathers has started rolling out.3

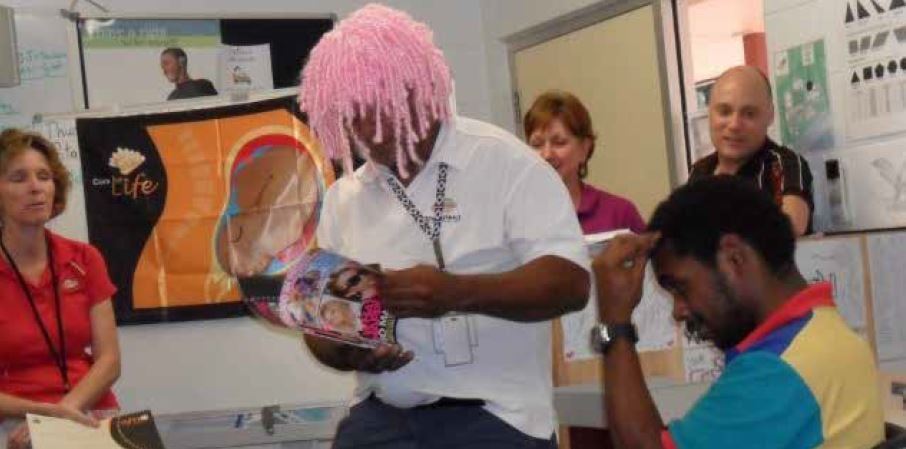

Fathers’ Program health coordinator, Bernard David, makes a point with some male Indigenous school students.

‘We the Aboriginal males from Central Australia and our visitor brothers from around Australia gathered at Inteyerrkwe in July 2008 to develop strategies to ensure our future roles as husbands, grandfathers, fathers, uncles, nephews, brothers, grandsons and sons in caring for our children in a safe family environment that will lead to a happier, longer life that reflects opportunities experienced by the wider community.

‘We acknowledge and say sorry for the hurt, pain and suffering caused by Aboriginal males to our wives, to our children, to our mothers, to our grandmothers, to our granddaughters, to our aunties, to our nieces and to our sisters.

‘We also acknowledge that we need the love and support of our Aboriginal women to help us move forward.’

Ross River Statement, July 2008

There are a number of key areas where there is an evidence base for interventions targeting males, as well as areas that are fairly intuitive in this social context. Gilligan’s paper4, on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women’s knowledge and attitude to smoking during pregnancy, showed a good understanding of the harmful effects of tobacco for these antenatal women, but what drove the reinforcing of tobacco smoking for them were key issues such as: having an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander partner; having a partner who smoked; and the number of smokers in the household, as well as high stress levels (often related to partner).

Also, Hunter’s work5, describing ‘stress hormone’ rises for pregnant Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women at pension day, showed significant responses based on the increased risk of violence on these days, with potential implications for the fetus and the mother.

The importance of quality family relationships, such as effective and loving parenting, is well established for children to obtain a better start in life with evidence around adverse childhood events and exposure to trauma, such as family violence, abuse and neglect, and substance misuse being the key to later life outcomes in chronic disease and mental health and wellbeing.6

Fathers’ programs

Based on broad evidence, Apunipima Cape York Health Council’s fathers’ programs attempt to address these areas of need, including: engaging young fathers, ensuring they are seen as part of the family structure and have an important role to play in protecting, caring and nurturing their families. Other areas include the following:

- Targeting the male partners of women who smoke during pregnancy to support her as well as quit themselves.

- Addressing fetal alcohol spectrum disorders by targeting the partners of females who do drink alcohol during pregnancy to conscript their support to help their partners not to drink during pregnancy, and often this means the male will need to stop drinking as well to provide this support.

- Education about the role of the partner in pregnancy – ‘why is she acting so weird?’ – and how to support these women.

- Educating Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males about positive loving relationships, how to treat women, women’s physiology, the father’s role with the newborn, the male role in contemporary society are all central to our programs.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men’s groups in many communities attempt to address these issues from a grassroots, organic approach and our programs fit with this as there is vast untapped potential in supporting these men to do their business, with improved outcomes for women and families.

As Neville Bonner, the first Aboriginal Senator, said:

‘As parents, uncles, cousins or brothers, we [Indigenous males] must take responsibility for the future of our young people…emphasis is placed on sporting personalities, but the best role model a son can have is a patient, caring father. The attitude towards life of the son will mirror that of the father, which is the way things used to be done before white settlement… I am convinced there is absolutely no reason why a system that worked so well in the past cannot work today.’

Former Senator Neville Bonner, NSW Indigenous Men’s Healing and Cultural Affirmation Conference, 1997

Author profiles

Dr Mark Wenitong, Adjunct A/Prof, James Cook University, School of Tropical Public Health, is from the Kabi Kabi tribal group of South Queensland. He is the senior medical officer at Apunipima Cape York Health Council, working on health reform across the Cape York Aboriginal communities. He was the senior medical officer at Wuchopperen Health Services in Cairns for the previous nine years. He has also worked as the medical advisor for the Office for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health in Canberra.

He is a past president and founder of the Australian Indigenous Doctors Association, was on the National Health and Medical Research Committee – National Health Committee, chairs the Andrology Australia-Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Male Reference group and sits on several other committees. He is a council member of the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies and a member of the Queensland Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander council.

Mark has been heavily involved in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health workforce policy and helped develop several national workforce documents. He sits on the COAG Australian Health Workforce Advisory Council. He is involved in several research projects and has worked in prison health and refugee health in East Timor, as well as studying and working in Indigenous health internationally. He was a member of the NTER review expert advisory group in 2008.

He is involved in clinical and policy work with the aim of improving Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health outcomes in Australia.

Bernard David is of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander descendant from Iama (Yam Island) in the Kalaw Lagaw Ya group and Kaanju Tribal group in Cape York Peninsula. He is the men’s health coordinator at Apunipima Cape York Health Council in the Family Health Team and is a current board member of Wuchopperen Health Service, a local Aboriginal Medical Service in the Cairns and surrounding area.

He has been active in male health for the past 12 years in Far North Queensland, and is passionate about improving health and well-being outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men and their families.

References

- Holding Men, Kanyirninpa and the health of Aboriginal men, Brian F Mc Coy, Aboriginal Studies Press, 2008.

- A National Framework For Improving the Health and Wellbeing

of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Males, Working Party of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Male Health & Well Being Reference Committee, Office for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health, Canberra, 2003. - Australian Government Strong Fathers Strong Families Program, Department of Health and Ageing, http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/oatish-health-QandA_factsheet .

- Knowledge and attitudes regarding smoking during pregnancy among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women, Conor Gilligan, Robert W Sanson-Fisher, Catherine D’Este, Sandra Eades and Mark Wenitong, MJA 2009; 190 (10): 557–561.

- Hearts and Minds: Evolving Understandings of Chronic Cardiovascular Disease in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Populations, Hunter, Ernest, Aboriginal Studies Press, 2010, Issue 1.

- Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study, Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, Edwards V, Koss MP, Marks JS., Am J Prev Med. 1998 May;14(4):245–58.

Leave a Reply