The inaugural Alison Bush Memorial Lecture was delivered at the 2011 RANZCOG Indigenous Women’s Health Meeting by Her Excellency Prof Marie Bashir. This was followed by the first Alison Bush Oration, delivered by Dr Robyn Shields.

It was a singular honour to be asked to participate in the inaugural Alison Bush memorial lecture and a privilege to speak of her life and unique contribution. Alison Bush enlightened and enriched the lives of all with whom she came in contact. As a senior nurse in midwifery, with exceptional skills in both the practical application of her art and in contributing to the education of colleagues, medical students, senior consultants and Indigenous midwives in remote areas, she was accorded a unique honour by this College who conferred upon her an Honorary Fellowship.

At the time of her death, at the age of 68 in October 2010, it was estimated that hers was the first face seen by over 1000 newborns over four decades. Alison, the eldest of ten children, was born at Royal North Shore Hospital in September 1942, one of twin girls whose mother had been evacuated from Darwin following the World War II bombing raids on that city by the Japanese. Both Alison’s parents were from the Roper River area of Arnhem Land. They met however in the later years of their childhood at the Groote Eyland mission after their removal from family under the infamous, now discredited, policies of that period.

After the war, the family returned to Darwin, where Alison’s mother, working as a teacher’s aide, placed a high priority on the education of her children. Indeed, the twins were sent for several of their high school years to Bowral under the supervision of friends and subsequently they commenced their nursing training in Sydney.

Alison’s professional career began at Marrickville Hospital, Sydney, in 1960, and following further studies in midwifery and infant welfare in New Zealand, she began her illustrious years at Royal Prince Alfred Hospital in 1969. It was in this environment, a teaching hospital of the University of Sydney, which valued its association with the nearby urban Indigenous community of Redfern, and which received numerous complex referrals from rural New South Wales, that Alison became a valued advocate for Indigenous people. In all situations, she eloquently demonstrated the importance of cultural sensitivity and respect, bringing calm to sometimes chaotic situations.

Following her appointment in 1993 as the Aboriginal liaison midwife, she also provided consultation and education across all hospital departments and to community agencies, ever in demand for her expertise both within the hospital and the broader community. Across these years, she undertook a substantial responsibility in teaching and skills transfer, and in serving on a range of advisory and planning committees for the State of New South Wales and the nation. Her numerous prestigious awards included: the aforementioned Honorary Fellowship of this College as well as:

- Honorary Fellowship of the New South Wales College of Nursing

- Inductee in the Aboriginal Hall of Fame

- A finalist in the 2010 New South Wales Woman of the Year award

- The Centenary of Federation medal

- An Officer (AO) in the Order of Australia awards

But beyond her exceptional skills and numerous awards, Alison had an innate modesty, reflected in the quietness of her voice and the dignity of her presence. Nevertheless, she also had an extraordinary range of interests. Strengthened by her lifelong faith, she sang in the church choir. And from her days at school, she continued to play and to excel in sport, representing New South Wales in cricket in the 1960s and 1970s, and representative hockey in the 1970s.

It is noteworthy that during her illness last year, she recalled earlier years with delight, riding through the suburbs on her Vespa motorcycle, cracking the big waves at Bondi as they rolled into shore, attracting compliments from the local young surfers as she emerged from the water. Treasured memories held by Dr Robyn Shields and myself are of our travels with Alison to visit the sacred sites in Arnhem land and participate in gatherings of remote and rural health professionals.

It is with a deep sense of gratitude that we reflect upon Alison’s life. And we know how deeply touched and proud she would be to know that we have gathered here together to honour her. I thank you all.

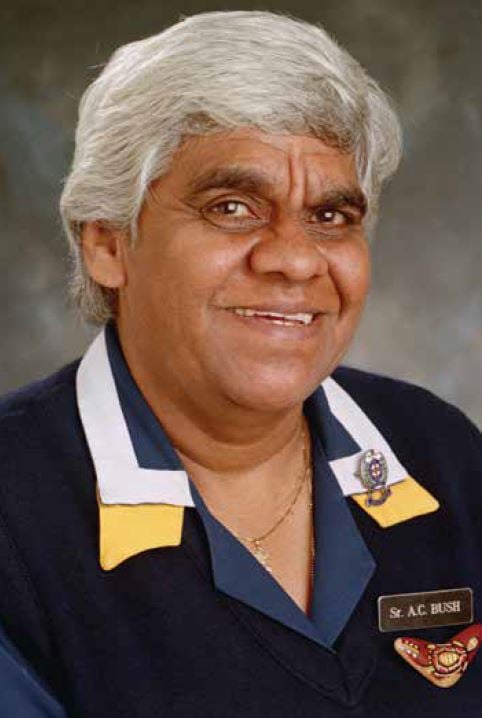

Sister Alison Bush

The Alison Bush Oration

First, I would like to acknowledge the traditional owners, past and present of whose land we gather on today.

I am honoured to be able to present the first Alison Bush Oration. Sister Bush, as she was fondly referred to by many who knew and respected her, was certainly a trailblazer, not only in nursing but also in the much-respected area in which she practiced as a midwife at Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, in Sydney. Her lifelong career was dedicated and committed to the health and wellbeing of mothers and babies from all walks of life. Her love of Indigenous people was certainly a hallmark of her practice and she was known and respected by both many Aboriginal people and her peers, both nursing and in the medical field. All stood in awe of her presence, wisdom and sense of humour.

My professional background is not in O and G, but I have had a long association working in mental health and mostly dedicated to Aboriginal mental health. In the earlier years of my career, Alison and I shared many patients, most of whom were expecting a child and either had a mental illness or suffering mental distress. Our personal and professional lives were intertwined and helped build the foundations of a lasting friendship and bond. My years working in the field of mental health, working with some of the most disadvantaged groups in the mental health system and in the prison system in New South Wales, were an absolute privilege. It was here that I developed a loving and long friendship with Prof Bashir who has been a mentor and inspiration to many of us, including Alison.

When I look back at my childhood, I have no doubts that I was destined to work in the area of mental health and with people who have suffered from a serious mental illness or disorder during some stage in their life’s journey. I grew up in South East Queensland and our family home overlooked a large psychiatric institution called Sandy Gallop. The name changed later to Challinor Centre and it is now home to the University of Queensland. I can clearly recall passing by the large institution with its high barbed-wired fences. No one really talked about Sandy Gallop or about the people who were housed there, willingly or unwillingly.

Our history tells us that most psychiatric institutions were established to separate and protect the mentally ill and also to house those who were considered criminally insane. In among this hidden population it was easy to find Aboriginal people incarcerated behind the walls of the asylum, but most of these belonged to the generations who undoubtedly were unwillingly separated from their families.

For decades, Aboriginal people have been subjected to and have endured the continuation of bad policy decisions that have often resulted in long-term negative intergenerational consequences. These negative consequences have now become the foundation of our existence. We as Aboriginal people are no longer the proud hunter and gatherers of this land, but have become a group of people disempowered and alienated from participating in mainstream society. Government policies that are made on the run or in response to crises will often end in disasters. With the evidence that the development and implementation of policies that enable crises and negative cycles to continue and go on unchallenged, it is almost as though no one has learnt from our past mistakes.

The individuals I have worked with who have personally experienced separation from their families often tell heart-wrenching stories of travelling along a traumatic pathway associated with the poorest mental health and unbearable emotional pain. Their personal stories start with a familiar beginning and end with the most predictable outcomes. I am sure most workers sitting here today will have heard similar stories that often go like this:

‘I was removed from my mother or family at a very young age. I can remember being placed into foster home after foster home, because my stay was only meant to be a short one. I did not have an opportunity to form relationships with my carers because I was moved around so often. I rarely saw my birth mother or family and I don’t really know who my family are. While I was in foster care, I was subjected to mental abuse, emotional deprivation and neglect or was subjected to forms of physical abuse. At a young age I started drinking and taking drugs to take away the pain, because I felt I had no one who could help me. I have no friends and have been admitted to psychiatric hospitals a couple of times and have been in and out of prison. At least in prison I have a routine, given three meals a day and a bed. Prison has given me a sense of belonging.’

These stories are far too common and are the depiction of the confronting realities that individuals have had to deal with in a lifetime. For individuals whose early separation from their only source of identity create patterns of certain coping behaviours, which set up cycles of helplessness and or hopelessness that often ends in disastrous outcomes.

This brings me to mention one group of people I would like to draw attention to. These are the individuals who are now sitting in Juvenile Justice Facilities or in the prison system. In general, there is very little sympathy for people in prisons and this is for all sorts of reasons and beyond this discussion today. However, this is a population that is booming and out of proportion, in particular for Indigenous Australians. More money is now spent on building prisons and less on education and schools.

The current rate at which Indigenous people are being incarcerated is in an upward trend and not abating. Incarceration in itself has major implications on the health and mental health of individuals as well as on Indigenous families and communities.

In June 2009, the census showed the Australian prison population to be just over 29000, 93 per cent were male prisoners; however, overall 25 per cent of this population is Indigenous. Between 2008 and 2009, the general prison population increased by six per cent, but for Indigenous people the prison population increased by ten per cent.1

It was found that those Indigenous Australians who were removed from their natural family were at significantly higher risk of arrest. Close links were found with early childhood trauma and the increased risk of juvenile involvement in crime. It is well documented, as far back as the 1970s and early 1980s in a number of studies, that children in sole-parent families are at heightened risk of involvement in crime, particularly where the sole caregiver was poor and or lacked close friendships and social supports.2 Groups from lower socio-economic status and living in poverty have been known to have strong correlations to both juvenile and adult involvement in crime. For a long time it was thought that this correlation simply reflected bias exercised in police discretion. It is now clearer there is a relationship between economic wellbeing and offending. Other factors, such as financial stress, increase the risks of child neglect and abuse, plus other parenting problems.

In 2009, an epidemiological survey of prisoners in general, consistently found higher levels of physical ill health, psychiatric illnesses, communicable diseases and engagement in risk behaviours such as illicit drug use. For Indigenous offenders it was noted that they were further disadvantaged as they suffered more prone to ill health and died at much younger ages. Their disadvantages were compounded by the fact Aboriginal people had reduced educational attainment leading to fewer opportunities in order to gain meaningful employment or employment at all because of their criminal background restricted them to types of employment.3

This is not new information. There were two major reports published in the 1990s: the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody and the Bringing Them Home Report: The Separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children from their Families. Both reports found that removal of individuals from their families leads to incarceration and is linked to poor health and mental health outcomes as well as dying preventable, premature deaths.4,5

April this year marked the 20th anniversary of the handing down of the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody, which investigated 99 deaths in custody. Since that report’s release, there have been 269 Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander people who have died in custody.

For generations of Aboriginal people, the ongoing cycles of trauma, a profound loss of identity and never experiencing a sense of belonging are stories that are daunting, but to have lived life in such circumstances would be even more terrifying. We need to ask ourselves: why in 2011 this is still a common story? Today, for those of us who are in positions of responsibility and working with families, infants, children and young people, I believe the greatest challenge is to maintain solid family foundations and community unity. This is essential to the restoration of the health our Indigenous people.

There are reasons why the present health and social crises exist. These are complex issues that are deeply rooted in the problems that have been mentioned thus far. The evidence is clear and the pathway forward for current and future generations is to stop the pervasive destruction from past and current practices of separating and alienating individuals from their communities. Maintaining strong family units and well communities is sometimes very

much dependent on the decisions that we make as clinicians. I urge every clinician not to be influenced by kneejerk reactions, but to seriously think through both the short- and long-term consequences of our actions. We need to examine the practice and urge to remove infants and children from their families. For the individuals who experience this have a long and lonely road back to their rightful place in a community and to earn the respect they rightfully deserve. We have to ask: can we do things differently and are our short-term solutions in the best interest of this child?

For all of us who work together – in health, social services or government departments – the solutions must be rooted in a better understanding of the impact of colliding cultures. The failure to recognise and accept the cultural differences and practices between groups brings about divisions and is a modern-day weapon to destroy Aboriginal society as it corrodes social cohesions at all levels.

As I fondly look back on my long-term friendship with Alison, her message was simple. It was about hope, change and working together, the aim was for better outcomes for our Indigenous children. It is my message too: I believe there is hope and that the long-awaited change will come. I believe the foundation of that change is our responsibility to make a difference. We must all learn from past mistakes. Ignorance about the long-term suffering of individuals can no longer be an excuse for inappropriate decision-making. Poor communication between people is problematic and, when open communication is lost, trust is broken.

Leadership is about moving forward and including individuals or groups of interest in discussions when negotiating important policy decisions for our future generations. Cooperation and positive working relationships acknowledge and accept other people as equals in partnerships. Our responsibility is to speak out when something is seriously wrong. If we are serious about changing the future, let’s enable both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people the opportunity to close some chapters in our shared histories to be able to move on. In doing so, we must learn to work together to find ways to bridge the gap, before we can even attempt to close the gap.

These are edited versions of the speeches given by Her Excellency Prof Marie Bashir, AC CVO Administrator of the Commonwealth, and Dr Robyn Shields at the 2011 RANZCOG Indigenous Women’s Health Meeting.

Text reproduced with permission. Photo reproduced with permission of Sr Alison Bush’s family and the copyright holder.

The Alison Bush Trust Fund: her legacy

Alison had a unique presence, which is missed by so many of us at Royal Prince Alfred Hospital (RPAH), Camperdown, in Sydney. She could tell stories, make poignant observations and find humour in situations. Alison was a great friend and colleague. She was a wonderful advocate for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island women at RPAH, from all over the State, and she also encouraged these women to take an active role in their own healthcare. Alison would facilitate, but not fuss. She believed that the basis of all good healthcare was deep respect. Alison was passionate about education and she wanted Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island doctors, midwives and nurses to be as good as any non-Indigenous counterpart. Sister Alison Bush was an excellent role model to all involved in healthcare. Alison wanted Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island health workers to maximise their knowledge base and play a leading role in health education in local communities. On a locum to remote communities in the Northern Territory, I saw how devoted Alison was to her large family. She liked making connections between people and places.

In accordance with Alison’s wishes, expressed in the final days of her life, RPAH has established a memorial fund (The Alison Bush Trust Fund) to promote the health and well being of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island women and babies, through education. The organising committee consists of Dr Andrew Child, Dr Sue Jacobs, Mr George Long, Maureen Ryan, Dr Robyn Shields, Valerie Smith and Prof Paul Torzillo. Her Excellency, Prof Marie Bashir is the patron. Initial ideas for the fund include clinical placements for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island health professionals and assisting in a variety of other ways with education (for example, books, fees, equipment, possible conference registration fees for health workers).

Tax-deductible donations to the fund can be made by cheque, payable to the Alison Bush Trust Fund, and sent to the Executive Unit, RPA Women and Babies, Missenden Rd, Camperdown 2050.

Dr Sue Jacobs

FRANZCOG, consultant obstetrician and gynaecologist

Royal Prince Alfred Hospital

Author profiles

Her Excellency Prof Marie Bashir, the first woman to be appointed Governor of New South Wales, took up her office on 1 March 2001. Before becoming Governor, Dr Bashir taught at the Universities of Sydney and NSW, increasingly working with children’s services, psychiatry and mental health services, and indigenous health programs. At the time of her appointment as Governor of NSW, she was Clinical Professor of Psychiatry at the University of Sydney; Area Director of Mental Health Services Central Sydney; and Senior Consultant to the Aboriginal Medical Service, Redfern, and to the Aboriginal Medical Service, Kempsey.

Her interests have included juvenile justice, research on adolescent depression, health issues in developing countries, education for health professionals and telemedicine and new technologies for health service delivery. She was appointed an Officer of the Order of Australia, in 1988, for her services to child and adolescent health; and was invested by Her Majesty, the Queen, with the insignia of a Commander of the Royal Victorian Order (CVO) in 2006.

Dr Robyn Shields AM, is currently working at Royal Prince Alfred Hospital as a medical doctor; she is also a member of the Sydney Children’s Hospitals Network (Randwick and Westmead) Board. Previously, Robyn worked in mental health and, in particular, in the development of mainstream Aboriginal mental health services in NSW, working in partnership with the Aboriginal Medical Ser-vice at Redfern. Other interests have included working with, and developing services for, Aboriginal inmates at Corrections Health Service, now known as Justice Health.

Robyn remains actively involved in mental health and continues in her role and appointment since 1996, as a NSW Mental Health Review Tribunal Member. Robyn has contributed to developing National and State-wide policies and service development in both Aboriginal Mental Health and Aboriginal Health. Past appointments have included being a member of the NSW Child Death Review Committee. She has also been a member of the Aboriginal Health and Medical Research Council of NSW Ethics Committee and the National Health and Medical Research Committee – Indigenous Health. Robyn has a special interest in working with disadvantaged groups and encouraging positive working partnerships to enhance capacity building in the community. In 2002, to commemorate the centenary of Australia, she was awarded an Australian Centenary Medal and, in 2004, was awarded the Member of the Order of Australia (AM), both medals were in recognition of her services to Aboriginal mental health.

References

- Review of Offender Health. Australian Indigenous Health Infonet. Grace, J., Krom, I, Bulter, T, Midford, R. 2011.

- Weatherburn and Lind, 2001.

- Review of Offender Health. Australian Indigenous Health Infonet. Grace, J., Krom, I, Bulter, T, Midford, R. 2011.

- Indigenous Deaths In Custody 1989–1996. Office of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner. October 1996.

- Bringing them home. National Inquiry into the Separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children from Their Families. Human Right and Equal Opportunity Commission. 1997

I went to school at Bowral High in 1958 with Alison and Jennifer Bush – both excellent people and athletes. Can you tell me if Jennifer is still living? Would love to speak to her after all these years.