The Darwin Midwifery Group Practice has implemented an innovative model of maternity care for Indigenous women from seven Top End remote communities.

The population of the Northern Territory (NT) is small (around 230 000), with a large number of very small communities scattered throughout. Every pregnant woman living in a remote area of the NT is encouraged to travel to an urban centre where birthing facilities can support a safe birth for the mother and baby. Many women, however, experience difficulties in leaving their families and communities. For Indigenous women, in particular, these difficulties can include, but are not limited to: separation from family and community, with its associated loneliness and boredom; negotiating travel and hospital systems; language and cultural differences; encountering many health providers who are mostly strangers; and having to repeat the story of their medical history and situation many times. In addition, they often have complex social and emotional needs that they are not able to articulate. Sometimes, the impossibility of overcoming these difficulties leads the woman to return to her community instead of remaining in the urban centre and an aero-medical evacuation in an emergency situation may then be required.

The Darwin Midwifery Group Practice (MGP) is a continuity model of care that has been developed in an attempt to overcome these well-recognised barriers to optimal care for pregnant women from remote communities. Before setting up the Darwin MGP, an extensive consultation process was undertaken, including assessments and discussion with providers of other continuity-of-care models. The research was also informed by studies such as Charles Darwin University’s ‘1+1 = A healthy start to life: Targeting the year before and the year after birth in Aboriginal children in remote areas’ and the Northern Territory Department of Health’s Maternity Services Review 2007. This Review made 63 recommendations, including improving continuity of care for Indigenous women from remote areas. Funding for the MGP model came from the Northern Territory Government’s Closing the Gap initiative, with supplementary funding from the Federal Government’s National Partnership Agreement for Indigenous Early Childhood Development.

The MGP began in 2009 and is located in purpose-built rooms in a suburban setting close to the hospital. At the time of writing, MGP has the following staff members:

- a coordinator;

- an administration officer;

- an Aboriginal health worker (who is currently studying midwifery);

- six full-time midwives, as well as a holiday relief midwife;

- an Indigenous ‘Strong Woman, Strong Baby, Strong Culture’ worker; and

- a senior Indigenous woman chosen by her community to accompany women while in Darwin, including into the birth room.

An anticipated outcome of the introduction of the MGP was the provision of a career pathway for Indigenous staff in the area of maternal and infant care. Presently, the Aboriginal health worker in the MGP is in her second year of midwifery education (BMid) at the Australian Catholic University (ACU) in Brisbane in the away from base program. She attends residential courses in Brisbane four times a year. There are three other Indigenous women in the Northern Territory who are also undertaking midwifery studies at the ACU and all communicate frequently to support each other.

The Senior Indigenous woman, Concepta Narjic, who accompanies women from her community while they are in Darwin.

The MGP operates a caseload model and each full-time midwife is assigned up to 32 women per year. The MGP cares for all pregnant women from the seven communities covered by the service, regardless of their obstetric risk factors. Each woman is assigned a midwife after the first visit to a remote community health centre and when an estimated date of birth is known. Women are given the name and mobile telephone number of their assigned midwife and these details are entered into their notes. The staff in the remote health centre have photos of the MGP team and are able to discuss the model of care and identify the assigned midwife for the woman.

Antenatal care in the remote community is provided by remote health staff and communication with the MGP is by telephone and via an electronic medical record system. An MGP midwife and/ or Aboriginal health worker meets and accompanies the woman to any visit in Darwin for medical, ultrasound or any allied health appointments. The MGP also offers assistance to access Centrelink and other services. Transfer from remote community to Darwin is arranged at 38 weeks gestation (earlier if medically necessary). Normal-risk pregnancies are assigned to midwifery-led care, but in cases of complex need, antenatal and birth care is provided in collaboration with obstetric staff of the Royal Darwin Hospital.

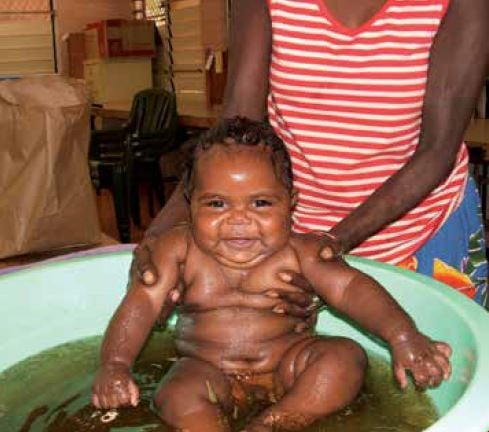

A healthy and happy mother and baby: the end goal for everyone working at the MGP. This baby is enjoying his bath in traditional bush medicine.

At all stages, and for all women, partnership with Indigenous staff is designed to respect and engender the feeling of cultural security and safety. MGP staff members encourage and facilitate education and each woman’s familiarisation with the hospital birthing facilities. An MGP staff member attends the birth, whether in the birth centre delivery suite or the operating theatre. The primary midwife has backup from two colleagues should she not be available to provide birth care owing to, for example, days off, annual leave or sick leave.

The MGP care does not end at birth – postnatal care and education are provided along with support for the woman and baby until they return to their community.

Whole-family approach

In general, Indigenous culture has recognised birthing as ‘women’s business’; however, more recently some requests for male partners to be more involved have emerged. The MGP encourages and supports partner involvement and has experience of some fathers participating in the birth, including the cutting of the baby’s cord. Unfortunately though, owing to distance and expense, most family members remain in the remote community. The introduction of mobile phone technology has at least allowed pictures of the new baby to be sent to those family members – often immediately following the birth.

Fathers’ involvement is encouraged by the MGP team. Mobile phones and digital cameras allow remote family members to stay in contact while women are staying in Darwin.

The difference is in the detail

The MGP model fosters close relationships between the expectant mother and the midwife/Indigenous health worker and this has been augmented by the use of mobile telephones for calls and text messaging. MGP staff members are able to follow up on any missed appointments and, as a result, women are much less likely to fall through the cracks. Moreover, information sharing with other healthcare providers leads to their increased understanding of the lives of women and their families. This advocacy role is one that the MGP team values.

Since the MGP model has been in operation, there has been an increase in the early discharge of babies from the special care nursery, supported by daily visits and breastfeeding guidance from MGP. In addition, improved communication and coordination of care with remote health staff has been appreciated. Staff in remote area health centres report that women speak favourably about their birth experience, remember their midwife’s name and can identify her in photos.

The MGP model of care is being extensively evaluated by researchers from the Charles Darwin University using a participatory action research model. The results of the evaluation will be available later in the year.

Leave a Reply