Hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy at term

Newborns affected by moderate or severe hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy (HIE) constitute 0.5 to 1.0 per 1000 live births in technically developed countries.1 Up to 25 per cent of survivors have long-term neurological sequelae, including cerebral palsy and intellectual impairment.2 Following an hypoxic insult, neuronal cell death occurs in two phases3,4,5, with the immediate phase as a consequence of energy failure within the neurone due to hypoxia. Six hours later, the secondary phase occurs as a consequence of hyperaemia; cytotoxic oedema; mitochondrial failure; excitotoxin accumulation; synthesis of nitric oxide; and free radical damage.6 It is during this delayed phase that encephalopathy occurs associated with seizure activity, which may be ameliorated by hypothermia.

It is postulated that hypothermia may be neuroprotective by its modification of cells programmed for apoptosis.7 Neuronal protection may also occur as a consequence of decreased cerebral energy requirements, altering the release of glutamate and dopamine, and decreasing nitric oxide and free radical production.8

What is the evidence for hypothermia?

Jacobs and colleagues describe the outcome of term and near-term infants in randomised trials of hypothermia after a hypoxic-ischaemic event in a Cochrane review.9 This review includes both whole body cooling and selective head cooling trials. Meta-analysis of eligible trials shows a significant reduction in death or major neurodevelopmental disability in the group of infants treated with hypothermia, independent of the type of cooling method.9 A recent multi-centre trial performed in China has also found a reduction in death and severe disability.10 A recent meta-analysis of the neurological outcomes at 18 months has shown that hypothermia increased survival with normal neurological outcome, with a number needed to treat of eight.11 Across Australia and New Zealand, hypothermia for moderate to severe HIE in the term newborn has become standard practice, with data being collected by the Australian and New Zealand Neonatal Network (ANZNN).

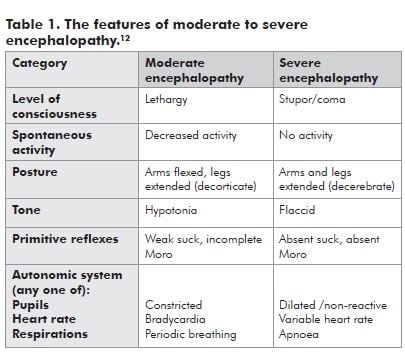

Criteria for treatment with hypothermia

The following are the current criteria for treatment with hypothermia as used by most Australian centres:

- neonates at 35 weeks gestation or older;

- less than six hours of age;

- evidence of moderate to severe encephalopathy;

- evidence of intrapartum hypoxia with at least two of the following:

- Apgar score less than or equal to five at ten minutes;

- mechanical ventilation at ten minutes;

- cord pH less than 7.00 or an arterial pH less than 7.00 or base deficit greater than 12 within 60 minutes of birth.

Minimal equipment is required to commence hypothermia in a non-tertiary facility. Monitoring of ECG, pulse oximetry and blood pressure, along with temperature management are the main requirements. The aim is to achieve an axillary or rectal temperature between 33 and 34 degrees Celsius. This may be achieved by either passive cooling (that is, not warming the neonate by overhead heater), or by active cooling, for example, by applying a cold pack under the head and across the chest. Adverse effects of hypothermia include bradycardia, hypotension, coagulopathy and an obvious requirement for monitoring. Clinicians looking after neonates with a moderate-severe hypoxic insult in non-tertiary facilities should discuss commencement of hypothermia with their local tertiary facility. All infants commencing hypothermia must be transferred to a neonatal intensive care unit for ongoing management.

Hypothermia has been shown in a number of large randomised controlled trials to reduce the incidence of death and severe disability following a moderate-severe hypoxic-ischaemic insult. The treatment is easy to commence, and is safe and well-tolerated. It should be considered in all term neonates fulfilling the current criteria. Continued monitoring of outcomes of neonates suffering a moderate-severe hypoxic-ischaemic insult treated with hypothermia is ongoing at both state and national levels.

References

- Levene MI, Sands C, Grindulis H, Moore JR. Comparison of two methods of predicting outcome in perinatal asphyxia. Lancet 1986; 8472:67-69.

- Vanucci RC. Current and potentially new management strategies for perinatal hypoxic-ischaemic encephalopathy. Pediatrics 1990; 85:961-968.

- Gluckman PD, Williams CE. When and why do brain cells die? Dev Med Child Neurol. 1992; 34:1010-1014.

- Lorek A, Takei Y, Cady EB, Wyatt JS, et al. Delayed (‘secondary’) cerebral energy failure after acute hypoxia-ischaemia in the newborn piglet: continuous 48-hour studies by phosphorous magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Pediatr Res. 1994; 36:699-706.

- Penrice J, Cady E, Lorek A, Wylezinska M, et al. Proton magnetic spectroscopy of the brain in the normal preterm and term infants, and early changes after perinatal hypoxic-ischaemia. Pediatr Res. 1996; 40:6-14.

- Inder TE, Volpe J. Mechanisms of perinatal brain injury. Semin Neonatol. 2000; 5:3-16.

- Edwards AD, Yue X, Squier MV, Thoresen M, et al. Specific inhibition of apoptosis after cerebral hypoxic-ischaemia by moderate post-insult hypothermia. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 1995; 217:1193-1199.

- Globus M, Alonso O, Dietrich W, Busto R, Ginsberg M. Glutamate release and free radical production following brain injury: effects of post-traumatic hypothermia. J Neurochem. 1995; 65:1704-1711.

- Jacobs SE, Hunt R, Tarnow-Morid WO, Inder TE, Davis PG. Cooling for newborns with hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007; (4):CD003311.

- Zhou WH, Cheng GQ, Shao XM, Liu XZ, et al. Selective head cooling with mild systemic hypothermia after neonatal hypoxic-ischaemic encephalopathy: A multicenter randomised controlled trial in China. J Pediatr. 2010; Epub ahead of print.

- Edwards AD, Brocklehurst P, Gunn AJ, Halliday H, et al. Neurological outcomes at 18 months of age after moderate hypothermia for perinatal hypoxic-ischaemic encephalopathy: synthesis and meta-analysis of trial data. BMJ 2010; 340:c363.

- Sarnat HB, Sarnat MS. Neonatal encephalopathy following fetal distress. A clinical and electroencephalographic study. Arch Neurol. 1976; 33:696-705.

Leave a Reply