Many women with health problems also experience particular issues during pregnancy, including deterioration of their underlying problem, fetal risks either from the condition itself or the medication used to treat it, or specific pregnancy, delivery or postnatal problems.

These women, who would particularly benefit from pregnancy planning, often also have limited choices with their contraception, making this a challenge. This article outlines issues associated with many of the commoner conditions.

Increasingly, long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) is favoured by providers and couples as it does not require action every day or with every act of sexual intercourse, this is easier and leads to higher contraceptive efficacy. LARCs include implants, injectables and intrauterine contraception and all have failure rates of considerably less than one per cent each year.

Combined oral contraception (COC) containing estrogen is the most likely method to be contraindicated for women who already have an underlying medical condition. When considering COC, does this condition:

- Increase the risk of arterial or venous thrombosis;

- Predispose to arterial wall disease or severe hypertension;

- Adversely affect liver function;

- Show a significant degree of sex hormone dependency; or

- Require treatment with an enzyme inducer?1

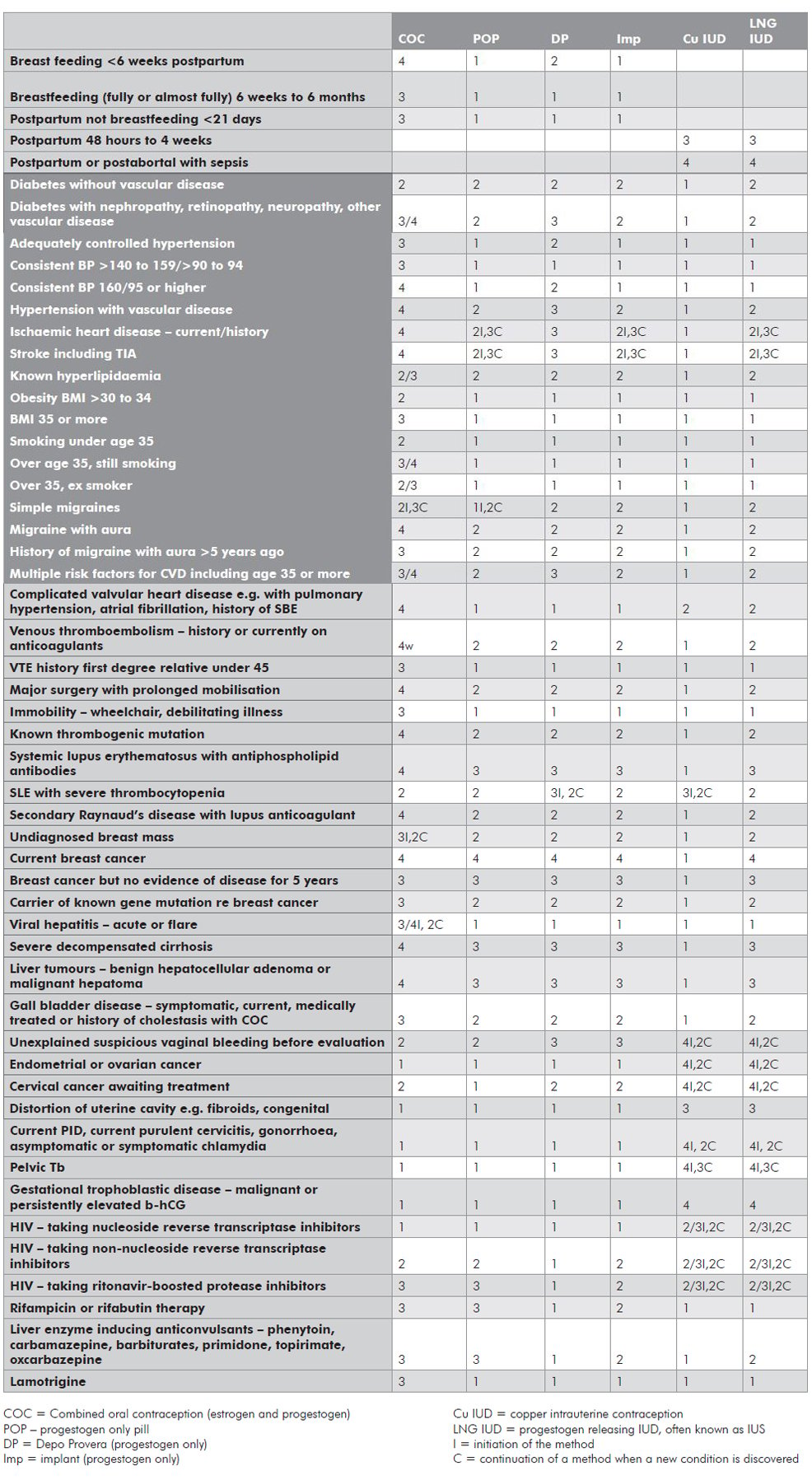

If so, a COC is contraindicated. In many cases, a progestogen-only method (implant, injectable or pill) will be suitable. The World Health Organisation (WHO) developed tables to indicate the risk of various contraceptive methods for men and women with different conditions. These have been modified by the UK Faculty of Family Planning and Reproductive Health Care for use in developed countries (see Table 1).

Table 2 (WHO), using categories, provides an excellent summary of risk assessment for various forms of contraception in relation to specific medical problems. Conditions, in the shaded part of the table, predispose to arterial disease. These arterial risk factors are related to diabetes; ischaemic heart disease/stroke; obesity; smoking; migraines; hyperlipidaemia; and increasing age. Testing for hyperlipidaemia is triggered by a history of a first-degree relative who has premature ischaemic heart disease or stroke (under the age of 45). When considering a COC, more than one of these arterial risk factors increases the WHO category, for example, BMI over 35 (WHO3) plus smoking under age 35 (WHO2) = WHO4. Age over 35 is considered as a risk factor if not already allowed for, for example, simple migraine (WHO2 for initiation, 3 for continuation) = WHO3 for initiation and 4 for continuation of COC for an older woman.

There are fewer venous risk factors for COC – obesity, history of a first-degree relative who had a deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolus before the age of 45, immobility and extensive varicose veins. Once again, each additional risk factor increases the rating by one, for example, obesity (WHO3) and immobility (WHO3) = WHO4 for COC.

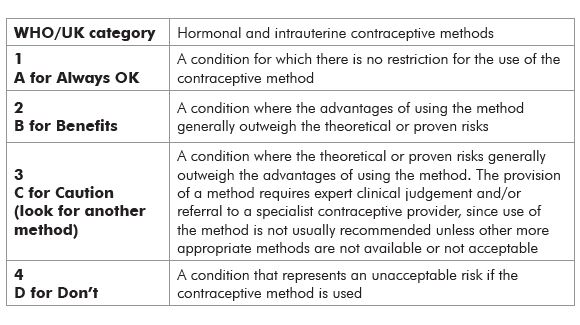

Table 1: What each category means.

Table 2. World Health Organisation 3 and 4 conditions for contraceptive methods.

Migraines

A simple migraine may be described as a unilateral or bilateral throbbing headache that is accompanied by nausea and vomiting, photophobia and blurry vision. It is severe and not usually relieved by aspirin or paracetamol.

An aura usually precedes a headache and almost always has a visual component affecting the same hemifield for each eye. It starts with a bright blind spot, which may increase to a C-shaped area with zigzag edges or the sufferer may experience flashing lights. Some women go on to have tingling in a hand or one side of the tongue, then difficulty finding their words (nominal dysphasia). Migraines with aura are associated with an increased risk of an ischaemic stroke when using a COC.

It should be noted that if a contraceptive method, such as a combined oral contraceptive pill, is being used as a therapy as well, the WHO categories do not apply so strictly. An example is that a COC may be considered for an obese woman with polycystic ovarian syndrome, as it is being used therapeutically as well as for contraception. An alternative for this woman may be metformin with another method of contraception, such as a progestogen-only or intrauterine method.

Comments on other conditions

- Previous pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) is not a contraindication to IUD/IUS use (if she has had a pregnancy since the PID episode, she has already proven that the PID did not cause infertility).

- It is common to treat asymptomatic chlamydia at the time of insertion of an IUD/IUS, as long as there is little risk of a repeat infection. It has been shown that the risk of PID when an IUD is inserted in untreated chlamydia is low, unlike gonorrhoea where it is significant. (A check for sexually transmitted infections before or at the time of insertion is generally recommended to enable treatment first.)

- The New Zealand Heart Foundation does not recommend prophylactic antibiotic cover for women with valvular heart disease or artificial heart valves for IUD insertion or removal unless there is local genital infection – amoxicillin or, if allergic to it, vancomycin can then be used. Antibiotic treatment would therefore not be needed for insertion as this would not proceed in the presence of active infection.3

- A history of ectopic pregnancy is not a contraindication to any method as all reduce the risk of pregnancy, however, methods that prevent ovulation are best.

- Mildly abnormal liver function tests would not prevent hormonal contraceptive use – only acute hepatitis or severe liver disease.

Some common scenarios

- A young diabetic woman. First, one needs to check whether she has already got signs of arterial disease such as retinopathy or renal disease. If she has, a COC would be contraindicated but she could use any progestogen-only or intrauterine method. If she has no current signs of arterial disease, but has any of the arterial risk factors listed – overweight, smoking, migraines (even a simple migraine), hypertension, hyperlipidaemia or she is 35 years old or more – she cannot use a COC.

- A woman with epilepsy. Estrogen has a tendency to increase the frequency of convulsions and progesterone to decrease them. This is not usually a problem for COC users, but progestogen-only contraception may help when epileptic control is difficult. If an epileptic woman is taking a liver enzyme-inducing anticonvulsant (see list in table) she will have to use a higher dose COC, such as Microgynon 50. Breakthrough bleeding suggests the dose is not high enough and two 30mcg estrogen COCs daily can be used. Progestogen-only pills and implants will not be effective enough while on enzyme-inducing medication, so she will have to use an injectable, intrauterine or barrier method. Lamotrigine blood levels may be decreased in COC users. Women using Depo Provera can have their injection at the usual 12 weekly interval.

- A nulliparous young woman wants to use a COC – her mother had a deep vein thrombosis (DVT) during pregnancy while in her 20s. As DVTs are commoner soon after commencing a COC and this young woman has not experienced the higher estrogen levels of pregnancy, it is important to check whether she has a thrombophilia before prescribing her a COC. If one knows that the mother had a thrombophilia, the specific abnormality can be checked. Otherwise, the commoner types are tested for by requesting activated protein C resistance and prothrombin mutation. She could start a progestogen-only method once she has had the blood test taken and remain on that if an abnormality is found.

When it comes to permanent contraception, there can be a dilemma about which partner should have the procedure. If the woman has a life-threatening condition, her partner may want to remain fertile for the future, but she may not be in a good physical state to withstand surgery. The recent introduction of the Essure system, with hysteroscopic placement in the fallopian tubes, may be particularly appropriate in this situation.

Ideally, a couple should use a contraceptive method that they themselves like, as this should lead to good continuation rates. However, when a woman has a health problem, the couple may have to look at another method that they may not be so happy to continue with. Good counselling is, of course, essential when choosing a contraceptive method or if problems arise during its use.

References

- Guillebaud J. Contraception: your questions answered. Churchill Livingstone Elsevier. 5th edition; 2009.

- Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare. The UK medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use, summary sheets. Available from http://www.ffprhc.org.uk/admin/uploads/UKMECSummarySheets2009.pdf [link expired; search “UK MEC Summary Sheets” at www.fsrh.org for current reference].

- The National Heart Foundation of New Zealand Advisory Group. Guidelines for the prevention of infective endocarditis associated with dental and other medical interventions. Available from http://www.heartfoundation.org.nz/files/Infective%20Endocarditis%20Guide.pdf.2008.

Leave a Reply