The epilepsies comprise a group of disorders characterised by recurrent seizures and classified according to clinical or specific electroencephalographic (EEG) features.

Although epilepsy is the most commonly encountered neurological disease in pregnancy, it is still relatively rare, with a prevalence of 0.6 to 1.0 per cent. Medical therapy utilising antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) is the most common form of treatment, although surgery or no treatment may have a role in specific cases.

Preconception care

Ideally, all women with epilepsy should undergo counselling prior to pregnancy. The principles of drug review at this time are:

- Withdraw any unnecessary medication where possible.

- Use monotherapy where possible.

- Use the smallest effective dose of medication.

- Withdraw drugs with potential adverse fetal effects and replace with safer drugs if possible.

In the case of epilepsy, tampering with stable and effective medication does carry hazards for the patient. AED therapy is usually chosen with great care by the patient’s neurologist and often after the failure of other drugs. For these reasons, it is advisable to consult with the neurologist before making any substantive change.

Preconception counselling may identify women who have been seizure-free for a number of years on minimal medication, particularly those with a normal EEG and normal cerebral imaging. In these cases, careful weaning of therapy over six months prior to pregnancy may be entirely appropriate, accepting a small risk of recurrence of seizures.

All women with epilepsy taking AEDs should receive high dose folate supplementation (5 mg), although the evidence for this being beneficial is limited. During pregnancy, antenatal screening for neural tube and cardiac defects with spine and nuchal translucency ultrasound should be performed at 12 to 13 weeks of amenorrhoea. Maternal alpha-fetoprotein testing at 16 weeks is less helpful. A careful 18 to 20 week morphology scan should be performed in a recognised centre. It is important to ensure the sonographer is aware of the patient’s additional risks for each of these scans. Most clinicians agree that, for both the mother and her fetus, the benefits of controlling seizures outweigh the potential risks associated with the AEDs. Monotherapy is associated with significantly fewer adverse fetal effects than polytherapy. The genetics of epilepsy are complex and advice regarding heritability should be guarded.

Pregnancy

A minority of women with epilepsy experience an increase in seizure frequency during pregnancy, particularly those with poorly controlled epilepsy prior to pregnancy. A prolonged seizure-free period prior to pregnancy (nine to 12 months) is associated with a high likelihood of remaining seizure-free during pregnancy. A small minority of women will deteriorate during pregnancy and this may be explained

by changes in AED pharmacokinetics, as well as vagaries of patient compliance. In practice, tiredness, nausea, vomiting, sleep disturbance and emotional stress may be important factors affecting seizure frequency during pregnancy. These factors may be magnified around the time of delivery and immediate puerperium, especially with sleep deprivation that is almost inevitable at this time.

Whether seizure disorders themselves may cause an increase in congenital malformations or adverse pregnancy outcomes remains controversial. Seizures have been reported to cause significant fetal heart rate decelerations, presumably secondary to maternal hypoxaemia and acidosis. Single seizures are unlikely to be a significant problem whilst modern treatment of status epilepticus has reduced fetal mortality substantially. Trauma during seizures can result in placental abruption or uterine injury, as well as the usual maternal hazards of self-injury and aspiration pneumonitis. Recent analysis of the association between epilepsy and adverse pregnancy outcomes such as preeclampsia, lower birth weight, caesarean delivery, late pregnancy bleeding, premature labour and stillbirth failed to demonstrate any increased risk.1

Antiepileptic drugs

During pregnancy, a number of factors influence drug levels, including altered absorption, protein binding, metabolism, renal clearance and non-compliance. Overall, there is a tendency to require an increase in AED dose during pregnancy. AED levels should be monitored by observation of the clinical response and regular (three-monthly) plasma unbound drug levels, where these are available. As the adverse effects of AEDs are believed to relate to peak levels, a change to smaller doses at more frequent intervals or sustained release preparations should be considered. Treatment should be maintained around the time of delivery and dosage reassessed postnatally, as toxicity may occur if the gestational higher dose is continued in the puerperium.

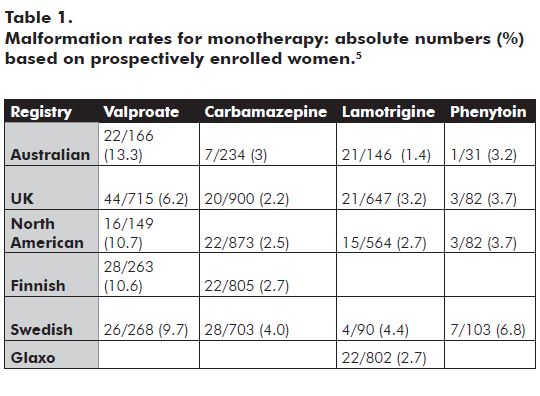

For most AEDs, transplacental drug transfer results in significant fetal exposure. This is true for both the older AEDs and newer agents. The use of AEDs during pregnancy has been associated with an increased incidence of congenital malformations, both major and minor, and neurocognitive impairment. Estimates of risk vary, but a recent study indicates 4.5 per cent (OR 2.6) frequency for AED monotherapy in utero exposure and 8.6 per cent (OR 5.1) for AED polytherapy.2 This compares with a background rate of 1.6 to 2.1 per cent. Determining the magnitude of these risks is extremely difficult as epidemiological data are highly variable and large, randomised prospective studies are neither available nor feasible. Observational data from a number of national prospective drug registers is gradually becoming available and is starting to contribute significantly to our knowledge in this area (see Table 1).

Strong epidemiological data exist implicating valproate (one to two per cent)3 and carbamazepine (0.2 to one per cent)4 as particular risk factors for neural tube defect, specifically spina bifida. The predominant malformations seen in women with epilepsy are cleft lip or combined cleft lip and palate (valproate 1.5 per cent, phenytoin 1.2 per cent, carbamazepine 0.4 per cent, lamotrigine 0.2 per cent) and cardiovascular malformations (phenytoin 1.2 per cent, valproate 0.7 per cent, carbamazepine 0.7 per cent).

Hypospadias and gastrointestinal defects are also overrepresented. The relative risk of facial clefting has been estimated at 2.7 for untreated epileptics and 4.7 for woman taking anticonvulsants. Although the relative risk of congenital malformation with valproate is higher than with alternative agents, overall, the risk of monotherapy is low. This should be taken into account when changes in therapy are contemplated, especially if other therapies have previously been unsuccessful.

Very limited information is available about the newer AEDs such as levetiracetam, topiramate, gabapentin, vigabatrin and oxycarbazepine. Any patients exposed to these agents should be enrolled in prospective registries to allow appropriate data collection.

Almost all of the older AEDs (benzodiazepines, carbamazepine, phenobarbitone or primidone, phenytoin, trimethadione, valproate) have been associated with the fetal AED syndrome consisting of minor malformations and dysmorphism, for example, hypertelorism; low-set abnormal ears; short neck with low posterior hairline; bilateral single transverse palmar creases; and distal digital hypoplasia. The incidence of this syndrome has varied with the population studied, but in general, the risk appears to be about ten per cent in exposed fetuses. Aspects of this syndrome also appear to occur more commonly in children of women with epilepsy, even when untreated. Many of these features improve with age.

The use of AEDs, particularly valproate, but also phenytoin (not carbamazepine), has been associated with neurocognitive abnormalities in the offspring of women with epilepsy. The neurocognitive risk associated with valproate monotherapy (and, similarly, the rates of major malformation) appear to be dose-related, with adverse outcomes only increasing when the total daily dose is above 1100 mg. Animal studies suggest these cognitive effects are mediated by accelerated neuronal apoptosis. Newer data have failed to show any increase in the risk of haemorrhagic disease of the newborn where standard neonatal vitamin K therapy (1 mg) is administered.

Delivery and postpartum

Stress, sleep deprivation, pain, hyperventilation and erratic absorption of AEDs contribute to an increased risk of seizures during the emotional turmoil of labour and the immediate postpartum period. The route of delivery should be selected on obstetric grounds, although precautions should be taken whatever the mode of delivery. All women with epilepsy should have a canula inserted on admission to the delivery suite. AEDs should be continued at pregnancy doses during and immediately after delivery, but reduced stepwise to prepregnancy doses over the first two or three postnatal days, as the increased requirements of pregnancy abate quickly. Where oral therapy is not possible, intravenous preparations of phenytoin, initially 10 to 15 mg/kg over approximately 20 minutes, then 100 mg IV every six to eight hours, may be given. Intravenous valproate at a dose of 400 to 800 mg (up to 10 mg/kg) by slow IVI, then 1 to 2 mg/kg/hr (max 2500 mg/day) is an alternative, particularly postpartum.

If seizures do occur, appropriate supportive treatment with protection of the airway, oxygen and monitoring of the fetal heart rate should be commenced. Most seizures are self limiting, however, if seizures are prolonged, treatment with intravenous clonazepam (1 to 2 mg over two to five minutes), lorazepam or diazepam (2 mg/min to max 10 mg) will usually terminate the seizure. Treatment with these drugs may cause maternal respiratory depression and fetal and neonatal sedation. Careful clinical assessment is required to exclude other causes of seizure in labour such as eclampsia.

The days following delivery are a time of particular risk for recurrent seizures. Adequate pain relief, assistance with mothercrafting, and measures to allow the new mother as much rest as possible will reduce the risk of postpartum seizures. Most AEDs are considered compatible with breastfeeding although the newborn should be observed for sedation. Levetiracetam, lamotrigine, topiramate and gabapentin are transferred into breastmilk at greater levels than other AEDs, but appear to be rapidly excreted by the newborn. Preconception counselling is important for any chronic medical disorder, including epilepsy. It is useful to encourage the woman to return for this purpose when she is considering another pregnancy, to review the state of her general health, her epilepsy and its treatment.

References

- Harden CL, et al. Practice parameter update: management issues for women with epilepsy – focus on pregnancy (an evidence-based review): obstetrical complications and change in seizure frequency: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee and Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and American Epilepsy Society. Neurology 2009 Jul 14; 73(2):126-32.

- Holmes LB, Harvey EA, Coull BA, et al. The teratogenicity of anticonvulsant drugs. N Engl J Med. 2001; 344: 1132-1138.

- Lindhout D, Schmidt D. In utero exposure to valproate and neural tube defects. Lancet 1986; 1(8494):1392-3.

- Kallen AJ. Maternal carbamazepine and infant spina bifida. Reprod Toxicol. 1994; 8; 203-5.

- Meador KJ, et al. Pregnancy registries in epilepsy: a consensus statement on health outcomes. Neurology 2008; 71(14):1109-17.

Leave a Reply