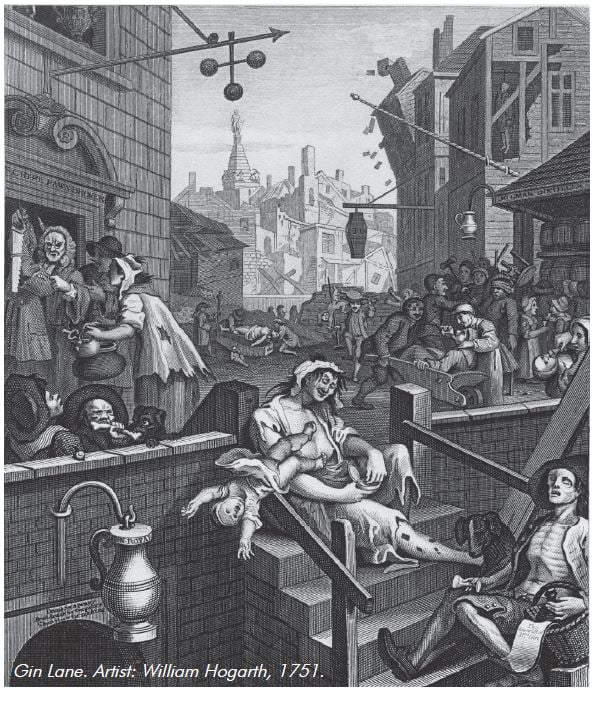

Substance abuse has been with us since antiquity. It is epitomised in the picture below of ‘Gin Lane’, issued in 1751 by English artist William Hogarth in support of the Gin Act, to depict the evils of drinking gin as opposed to the merits of beer.

The combination of ‘Beer Street’ and ‘Gin Lane’ showed those on Beer Street as happy and healthy and those in Gin Lane as living in poverty, depicting infanticide, starvation, madness, decay and suicide. The free market economy of the day leaves the occupants of Beer Street as prosperous, while making those of Gin Lane poorer. This is similar to today where the tobacco companies are growing rich whilst tobacco smokers are overrepresented amongst the poorest in our society. Gin Lane also depicts some of the more harrowing aspects of substance addiction which are still seen in some cases today – prostitution and drug use being of more importance than child-rearing. These are clearly extreme examples. The prints were published in the London Evening Post between 14 and 16 February 1751 with the intention of ‘shocking the lower classes into reforming’.1,2

On a per capita basis, there was more narcotic abuse in the late 19th century than in the late 20th century.3 Substance use and addiction is a worldwide phenomenon and affects the whole social spectrum. While there is heterogeneity in the drug scene from between locations, the clinical management and controversies are remarkably similar.

According to the 2004 National Drug Strategy Household Survey4, alcohol use decreased during pregnancy and/or breastfeeding from 85 per cent to 47 per cent. Illicit drug use decreased from 17 per cent to six per cent and smoking decreased from 22 per cent to 20 per cent. The highly addictive nature of cigarette smoking is reflected in the minimal reduction in smoking between the pregnant and non-pregnant state.

Determining whether a drug is teratogenic or has caused some form of problem for the mother and her baby is complicated by the interaction with environmental factors. Clearly, the amount of drug consumed per day has some influence. Polydrug use is common, hence teasing out all individual contributory drugs and environmental factors is extremely difficult.

There is a paucity of robust level 1/11 evidence in this field. Many recommendations have been based on case reports and case series from the 1970s which have been passed on through the reference cascade. Many of these case reports, case series, etc, would not be published in 2010 as they would not survive the rigour of the peer review process. However, it is not possible to perform high quality double-blind randomised trials with pregnant drug-using women and drug-exposed neonates due to ethical considerations. For instance, randomising pregnancies to receive stratified dose/frequencies of a particular licit or illicit drug and measuring outcomes is not ethically possible nor desirable! However, cohort studies both retrospective and prospective are affected by multiple confounders.

While some women with substance addiction are chaotic and only present in labour having had no antenatal care, many pregnant women with an opioid addiction are stabilised on methadone, hold down steady jobs, manage a family and engage in antenatal care.

National guidelines

In June 2006, the National Clinical Guidelines for the Management of Drug use During Pregnancy, Birth and the Early Development Years of the Newborn commissioned by the Ministerial Council on Drug Strategy under the Cost Shared Funding Model were published.5 These guidelines can be accessed from the New South Wales Health website (www.health.nsw.gov.au/pubs/).

This publication was a collaborative work between midwives, nurses, obstetricians, general practitioners, neonatologists, psychiatrists, psychologists, drug and alcohol physicians, social workers, researchers, a policy analyst and an international expert from the united States, Dr Karol Kaltenbach.

Medical problems

Medical problems include infectious diseases; poor nutrition; malabsorption; poor dentition; dermatological problems such as cellulitis and dermatitis artefacta; cardiovascular problems such as bacterial endocarditis and valvular heart disease; respiratory morbidity such as pneumonia; and neurological problems such as cerebrovascular accident (CVA) from emboli, Wernicke’s encephalopathy (alcohol) and peripheral neuropathy (inhalants).

Psychosocial problems

Women whose pregnancies are affected by a substance addiction are often complicated by and/or associated with poverty, homelessness, social isolation, a chaotic lifestyle, prostitution, criminal activity, family disruption, violence and trauma. 60 to 80 per cent of these women have psychiatric co-morbidity6 such as depression, anxiety disorder, mania, dysphoria and drug overdoses. A reported history of physical, psychological, emotional and sexual abuse is common. Subsequently, high levels of low self-worth, self-harm and eating disorders are reported amongst this group of women. They are more likely to have an unplanned pregnancy, be unemployed, be Indigenous, to have not completed their schooling and to be incarcerated.

Obstetric and perinatal complications

The reported increased obstetric complications include increased rates of miscarriage, perinatal and infant mortality, anaemia, abruption, preterm delivery and low birth weight. These women need more pharmacological analgesia during labour/delivery and in the postpartum period following caesarean section. Babies exposed to licit and illicit substances in utero are more likely to require admission to the special care nursery, to experience Neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) and to be medicated. These babies are more likely to be removed from their mothers by the local child protection authorities, to die from sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) and to be developmentally delayed.

Teratogenicity

There is a three per cent background rate of congenital abnormalities. To ascribe teratogenicity to a drug death, an observed above expected rate of a particular abnormality or series of abnormalities, growth restriction or functional disorders would need to be seen amongst the offspring of women using this drug exclusively. This relationship should be demonstrated to be dose-related and the fetus should be exposed during a critical period of development and is affected by an interaction of genetic and environmental factors.7

Detection of drug use and patterns of use in pregnancy

Detection of drug dependence by history and examination is the cornerstone of management of these complex pregnancies. This allows referral to the appropriate antenatal clinic, stabilisation of the patient onto legal alternatives, management of the medical and obstetric complications and provision of psychosocial support. Most obstetric units use a history of self-reporting, detailed interview and a screening questionnaire. Objective screening has been suggested, however, should this be universal or targeted? Which biological sample should be examined and which metabolite should be measured? There are ethical, legal and financial considerations of such an approach. There are certain clinical manifestations and psychosocial clues, for example, women who present in preterm labour having had no antenatal care, unkempt, needle tract marks, etc.

Many drug-addicted women who become pregnant are motivated to cease their habit and engage in healthcare. The marker for success in these cases is whether their partner also uses drugs. The women whose partners are also motivated to stop their drug use have a much higher likelihood of remaining drug free.

The HITS study6 showed that women reduced their drug use during pregnancy from the first trimester to 36 weeks gestation. However, by six months postpartum, their drug use was back to pre- pregnancy levels. Perhaps this is because the incentive (not exposing their fetus to drugs) has gone. We need to work out effective interventions to prevent this relapse.

Engagement and retention in care

Maternal and child wellbeing is enhanced by trust between patient and health professional. Continuity of caregiver, assurance of confidentiality, being treated with respect, allaying patient fears about being stigmatised and refraining from displaying patronising attitudes contribute to successful engagement of the patient in ongoing antenatal care. However, poor treatment, the sheer array of professionals seen in a multidisciplinary setting, fears that their baby will be apprehended, that they cannot cope and sometimes inconsistency of information, do not encourage patients to reattend. The importance of always thoroughly investigating increasing analgesia requirements was demonstrated to me once in a postpartum patient. Her increasing requests for analgesia for severe lower back pain were being interpreted as drug-seeking behaviour. She was subsequently diagnosed (after discharge from the maternity hospital) with a sacroiliac joint abscess!

Obstetric care

Most tertiary obstetric units in Australia and New Zealand run a multidisciplinary antenatal clinic for women with a chemical dependency in pregnancy staffed by midwives, obstetricians, drug and alcohol clinicians, a psychologist/psychiatrist, a social worker and a dietician. Both neonatal and developmental paediatricians are involved in planning neonatal and community care post-delivery depending on each individual patient’s circumstances. Whilst the majority of patients have regular visits to the hospital antenatal clinic, they are encouraged to maintain links with their local GP during their pregnancy. Some patients obtain their methadone from their GP. Some women prefer to use someone other than their GP as their prescriber if they are embarrassed about their drug dependence and do not want the GP they may have had from childhood and are familiar with their family to know. Indigenous women may prefer to use their local Aboriginal medical services. Whether home visiting in the antenatal and or postnatal period is of value is controversial.

Specific symptoms and conditions which present in this population are anaemia from deficiencies of iron, folate and/or vitamin B or as a result of chronic disease; constipation from the large doses of methadone required for maintenance in pregnancy; nausea and vomiting; skin conditions such as cellulitis; dental problems; and infections (sexually transmitted, respiratory, cardiac and idiosyncratic infections).

There can sometimes be overlap between drug-related effects and obstetric complications causing confusion in diagnosis. I was involved in the care of a patient who presented, having had no antenatal care, with mildly elevated blood pressure, proteinuria, low platelets, mildly elevated liver function tests (LFTs) and was diagnosed with HELLP syndrome and treated accordingly. Her intravenous opioid addiction had gone undetected for 18 hours until she began to withdraw and was found injecting herself in the ward bathroom. Postpartum she developed subacute bacterial endocarditis. In retrospect, it became clear that her blood pressure was most likely mildly elevated whilst being in labour. Her LFTs were elevated and platelets were low due to the developing infection. Subsequently, she underwent a mitral valve replacement.

Nausea and vomiting

Nausea and vomiting can be particularly intractable requiring hospitalisation, intravenous fluids, 5HT3 antagonists such as ondansetron and consideration of split dosage of methadone to reduce the serum peaks. Obviously, other causes of vomiting need to be excluded (for example, gastroenteritis, urinary tract infections, preeclampsia, etc). Prochlorperazine and metoclopromide are used as first-line, although prolonged use should be avoided due to the risk of extra pyramidal side effects, especially in younger women. Supplementation with pyridoxine and thiamine is recommended.

Addressing the psychosocial situation

This involves management of any psychiatric co-morbidity, assisting with accommodation and appropriate housing for a nursing mother, baby plus or minus partner, help with budgeting and benefits. If domestic violence has been elicited, moving the woman to a safe environment is paramount. Antenatal reporting to the local child protection agency in the setting of domestic violence, chaotic mental health situations and hazardous drug use may allow the social work team to address these problems thereby increasing the chances of the woman keeping her baby.

Hepatitis C

Hepatitis C is common amongst ever-intravenous drug users in the eastern states of Australia (90 per cent) compared with the rate in Western Australia (45 per cent).8 The detection of seropositivity mandates quantification of hepatitis C RNA and viral load and referral to gastroenterology for consideration of interferon therapy once the pregnancy and puerperium are over. A study is about to commence in New South Wales to evaluate the incidence and mechanisms of vertical transmission of hepatitis C.

Labour and delivery

It is essential that methadone is given on time. Non-compliance by clinicians is cruel and unprofessional and only causes withdrawal symptoms in the patient. I have seen this occur. unfortunately, the person who failed to administer the methadone had gone home and the person on the next shift then had to manage the patient’s opiate withdrawal. The high levels of smokers in this cohort (greater than 90 per cent) is commensurate with high prevalence of intrauterine growth restriction (IuGR) and placental insufficiency. In some cases, the placenta may not have the reserve for labour. Whilst reduced fetal heart rate variability is a common feature in women on opioids or other central nervous system (CNS) depressants, decelerations are always suspicious or pathological. Meconium-stained liquor and abruption are more common in this group of women. They also require more analgesia for labour and delivery. Nitrous oxide and regional anaesthesia are more appropriate choices of pain relief than opiates. Venous access is often extremely difficult to obtain.

Postpartum

Unless there are concerns about neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) the mother and baby should be together. Exceptions include planned apprehension to child protection services. A further tailoring of methadone is usually required. Co-therapies such as benzodiazepines may also need modification. Contraception and advice on pregnancy spacing should be provided. Comprehensive discharge planning which commences antenatally should be finalised. Ideally, there should be a seamless connection from the hospital into the community so that the patient knows where to access help with mother-crafting and other matters. Discharge from hospital should not be at the weekend. The patient should be aware of any planned follow-up appointments for her and her baby. There is an urgent need for more mother and baby units in Australia, so that women with drug addiction and co-related mental health problems can be monitored and supervised in the nursing of their babies, to try and reduce the current level of mother and infant separations.

Stabilisation to legal alternatives

Methadone is the recommended therapy of choice for opiate addiction.5 Withdrawal has a high relapse rate. Enough methadone needs to be given to prevent cravings, manage withdrawal symptoms and remove the euphoric effects of heroin. Stabilisation on methadone improves antenatal attendance, gestational age and birth weight at delivery. The trade-off is NAS. The daily dose varies in pregnancy depending on the amount of placental metabolism of the methadone and degree of protein-binding of the methadone. Withdrawal is not recommended due to the high relapse rate9 and the wide troughs and peaks to which the fetus is then exposed. Withdrawal should be discouraged but accommodated if the patient requests this, but only in the second trimester.

Buprenorphine, a partial opioid agonist and partial antagonist, is being used increasingly in pregnancy and several studies have shown no adverse effects in comparison to methadone.10

Naltrexone implants offer some hope for the future, as they would minimise NAS and have been successfully used in some cases (clinical experience and anecdotal evidence). However, far more work in the animal model and non-pregnant state need to be performed to establish safety and pharmacokinetics before its use can be recommended in the management of opioid dependence in pregnancy.

Polydrug use should be discouraged and women told of the high risk of IuGR and prematurity where methadone as well as street drugs are used.6

Effect of differenct drugs in pregnancy

Alcohol

Alcohol is socially acceptable, legal and the most commonly used substance. However, it is potently teratogenic in moderate amounts and may have subtle cognitive effects in the third trimester. It causes a spectrum of disorders from fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS)11 to fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASD) to fetal alcohol effects (FAE). FAS is characterised by distinct facial anomalies, pre and postnatal growth restriction and poor cognitive function and behavioural problems.11,12 The ‘safe’ level of alcohol consumption in pregnancy is not known although episodic bingeing is worse than chronic low level consumption. Abstinence is not recommended as this would cause panic and unnecessary termination of pregnancy if women had an alcoholic binge one night out when they were unaware that they were pregnant. Surely one glass of champagne to toast a wedding at 28 weeks is not going to have significant long-term sequelae.

Amphetamines

Amphetamines are often used with other drugs or replace opioids when the latter are not available. They have not been proven to be teratogenic, but are associated with pre term delivery low birth weight for gestational age and high levels of depression after prolonged use. It can mimic obstetric complications such as preeclampsia in the third trimester. The most potent of this family of drug is ‘ice’, which causes profound behavioural problems and in some cases fully blown psychoses and in some a deep depression in the ‘hangover’ phase. Ecstasy, the dance party drug, is the most commonly used of this class of drug and its use is usually stopped once the women knows she is pregnant. Despite its bad press and sporadic deaths, ecstasy causes fewer admissions to hospital emergency departments than alcohol use. There is conflicting data about the effects of benzodiazepines on the human embryo and fetus. Pooled data from case controlled studies increased incidence of oral clefts.13 But meta analysis data from cohort studies13 has shown no such association. The fetus exhibits benzodiazepine receptors by 15 weeks gestation. Abrupt cessation of any benzodiazepine should be avoided. The concomitant use of benzodiazepines with opioids in pregnancy increases the likelihood and the severity of NAS.

Cocaine

Cocaine is a potent vasoconstrictor. It affects dopamine receptors, produces a feeling of euphoria, is highly lipid soluble and alters opioid receptor densities. Cocaine increases the incidence of placental abruption and infarcts; IuGR; intrauterine hypoxia; preterm labour and delivery; fetal intraventricular haemorrhage; cerebral infarction; neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis; and maternal cardiac effects such as arrhythmias, myocardial infarction and cerebrovascular events. It is estimated to be used by two to three per cent women of childbearing age. ‘Cocaine arrests up’ headlines the Wentworth Courier, the local free advertising magazine of the affluent eastern suburbs of Sydney, this week.14 This substance is mainly, but not exclusively, used at ‘the high end of town’. However, it is one of the most teratogenic (together with alcohol). How many members of the medical profession use both of these drugs, yet show scant respect for the more vulnerable and disadvantaged in our society, who for various reasons, find themselves in the grip of substance addiction? Isn’t a double standard being perpetuated?

Marijuana

Marijuana is an effective treatment for nausea and vomiting, according to many of our patients. The National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) uSA 1998 estimated that 2.8 per cent of women used marijuana in the first trimester.15 There have been few human studies on its effects in pregnancy. The reports on its effects on birth weight for gestational age have been conflicting. It has been reported that long-term use causes schizophrenia and it is postulated that it may have behavioural, developmental and cognitive effects on the developing fetus. This is difficult to measure given the interaction with the home and parenting environment.

Heroin

Heroin is not teratogenic per se. Most of the poor outcomes are due to a combination of lack of antenatal care, poor diet, injection of other substances used to cut the street drug and the environmental milieu. It is often adulterated and causes unstable peaks and troughs in maternal and fetal blood. Heroin rapidly crosses the placenta.

Tobacco

Tobacco is the major preventable cause of poor pregnancy outcome. Twenty per cent of all pregnant women4 and more than 90 per cent in this population smoke during pregnancy (personal observation). Most of the obstetric and perinatal complications seen amongst intravenous drug users are probably due to concomitant smoking. Miscarriage; IuGR; preterm delivery; fetal death in utero (FDIu); abruption; neonatal death (NND); sudden infant death (SIDS); behavioural problems; and lung and respiratory abnormalities, are all increased compared to the general obstetric population.16 Smoking doubles the incidence of IuGR.17 There is a demonstrable dose-response relationship even after controlling for age, parity, maternal weight gain, pre-pregnancy BMI, GA, socioeconomic factors and ethnicity.18,19 Babies of smokers are 200 to 300g lighter on average than babies of non-smokers.20

Babies of smokers demonstrate altered critical autonomic reflexes21, unstable breathing, impaired arousal and catecholamine biosynthesis, increased susceptibility to stress, sudden death and disease in later life. These children are then more likely to take up smoking and become nicotine dependent.22,23,24

All of these findings may be mediated via nicotine receptors.25 So it is possible that the use of nicotine preparations in cessation of smoking may not negate some of these effects, even though it will improve the mother’s long-term health if she does stop smoking preterm delivery.

Despite this knowledge and the current television advertising campaign, one in five women continue to smoke during pregnancy, indicating the highly addictive nature of nicotine rather than character flaws in our patients. Recent legislation, changes in packaging and increasing the price of cigarettes is unlikely to change this significantly. Smoking is the only pleasure for some of our most disadvantaged patients. It is their way of de-stressing. Whilst we have to continue to advocate non-smoking, we could perhaps be more understanding of why this particular group of women do not find it easy to concur. This is especially true of those who have ceased their heroin and marijuana habit. In doing a practice station for MRANZCOG oral examination candidates

last year, I played the role of a patient who was a heavy smoker. After eight consultations, I (a non-smoker) became quite agitated about being repeatedly told to stop smoking! We may come across as being superior, smug and lacking any understanding of their circumstances. Sadly, smoking is now being replaced by obesity as the major health problem – few in this cohort of patients have a weight problem. As a population, we are stopping smoking and we are getting fatter – surely the two are related!!

Discussion points

Management of pregnancies complicated by substance abuse provides an opportunity for women and their babies to improve their health outcomes. Antenatal care does make a large difference to this cohort of women. My view is that all drugs should be legalised to bring the ‘industry’ above ground and remove the attraction to this area by the criminal element in our society. Doses and drug content would be known. The drugs would be cheaper, negating the requirement for risky activities to fund their habit. They would be more likely to engage in antenatal care and be open about the extent of their drug use and less likely to end up in jail. Safe injecting rooms would reduce their exposure to blood-borne viruses. We need seamless transition between hospital and community. Then mother and baby units may help more babies to stay with their mothers.

References

- Paulson R. Hogarth: Art and Politics, 1750-64 Vol 3. Lutterworth Press. 1993. ISBN 0718828755.

- Uglow J. Hogarth: A life and a world. New York: Farrar Straus Giroux. 1997. ISBN 0374528519).

- Courtwright D. Addicts who survived: an oral history of narcotic use in America 1923-1965. Knoxville: university of Tennessee Press, 1989:24.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2005). Statistics on drug use in Australia in 2004. AIHW Canberra, p63.

- National clinical guidelines for the management of drug use during pregnancy, birth and the early developmental years of the newborn. Commissioned by the Ministerial Council on Drug Strategy under the Cost Shared Funding Model. NSW Department of Health. June 2006.

- Bartu A, Sharp J, Ludlow J, Doherty D. Postnatal home visiting for illicit drug-using mothers and their infants: A randomised controlled trial. ANZJOG 2006; 46: 419-426.

- Kalter H. Teratology on the 20th century: environmental causes of congenital malformations in humans and how they were established. Neurotoxicology and Teratology 2003; 25(2): 131-282.

- Richardson R, Bolisetty S, Ingall C. The profile of substance-using mothers and their newborns at a regional rural hospital in New South Wales. ANZJOG 2001;41;415-419.

- Luty J, Nikolau V, Bearn J. Is opiate detoxification unsafe in pregnancy? Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 2003; 24:363-367.

- Kakko J, Heilig M, Sarman I. Buprenorphine and methadone treatment of opiate dependence during pregnancy: comparison of fetal growth and neonatal outcomes in two consecutive case series. Drug and

Alcohol Dependence 2008; 96(1-2);69-78. - Lemoine P, Harousseau H, Borteyru J and Menoet J. Children of alcoholic parents; anomalies observed in 127 cases. Quest Medicale 1968; 21; 476-482.

- Jones K, Smith D. Recognition of fetal alcohol syndrome in early infancy. Lancet 1973; 2(7836); 999-1001.

- Dolovich L, Addis A, Vaillancourt J, Power J, Einarson T. Benzodiazeoine use in pregnancy and major malformations or oral cleft: meta-analysis of cohort and case control studies. BMJ 1998; 317 (7162): 839-43, Sep 26.

- Wentworth Courier, Sydney, Australia. Wednesday 28th April 2010.

- NIDA 1998: National Household Survey on Drug Abuse. Washington DC: Government Printing Office.

- Malloy M, Kleinman J, Land G, Schramm W. The association of maternal smoking with age and cause of infant death. American Journal of Epidemiology 1988; 128(1)p46-55.

- Haug K, Irgens L, Skjaerven R, Markestad T, Baste V, Schreuder P. Maternal smoking and birthweight: Effect modification of period, maternal age and paternal smoking. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica 2000; 79(6)p485-489.

- Abel E. Smoking and pregnancy. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 1984; 16(4):327-38, 1984 Oct-Dec.

- Werler M, Pober B, Holmes L. Smoking and pregnancy. Teratology 1985 Dec; 32(3):473-81.

- Hebel J, Fox N, Sexton M. Dose-response of birth weight to various measures of maternal smoking during pregnancy. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 1988; 41(5):483-9.

- Nachmanoff B, Panigrahy A, Filiano J, Mandell F, et al. Brainstem 3H-nicotine receptor binding in the sudden infant death syndrome. Journal of Neuropathology & Experimental Neurology 1998 Nov; 57(11):1018-25.

- Shenassa E, McCaffery J, Swan G, et al. Intergenerational transmission of tobacco use and dependence: a transdisciplinary perspective. [Review] [164 refs] Nicotine & Tobacco Research 2003 Dec; 5 Suppl 1:S55-69

- Abreu-Villaca Y, Seidler F, Slotkin T. Does prenatal nicotine exposure sensitize the brain to nicotine-induced neurotoxicity in adolescence?Neuropsychopharmacology 2004; 29(8)p1440-1450.

- Abreu-Villaca Y, Seidler F, Tate C, Cousins M, Slotkin T. Prenatal nicotine exposure alters the response to nicotine administration in adolescence: Effects on cholinergic systems during exposure and withdrawal. Neuropsychopharmacology 2004; 29(5)p879-890.

- Cohen G, Roux J, Grailhe R, et al. Perinatal exposure to nicotine causes deficits associated with a loss of nicotinic receptor function. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the united States of America. 102(10):3817-21, 2005 Mar 8.

Leave a Reply