After the luxury of 30 years of city practice, I undertook six weeks training in fistula surgery in Ethiopia, in preparation for volunteering in Africa. My wife, Robyn, joined me during the first two weeks at the Addis Ababa Fistula Hospital.

Addis Ababa is a city of vast contrast encompassing shanty housing, streetfront stores and an exciting, bustling market among opulent Western style hotels and restaurants, shadowed by developmentally arrested high rises. Sheep and cattle meander through the crowded streets adding to the hubbub of rusting blue and white taxis and what seems to be most of the 78 million inhabitants of Ethiopia.

The Addis Ababa Fistula Hospital (AAFH) is a haven of splendour with its beautiful trees and shrubs. The Medical Director, Professor Gordon Williams, is originally a urologist from England. His hospital statistics indicate 97 per cent of fistulae are cured, but nearly 50 per cent will have residual urinary incontinence. Since anticholinergic medication has been allowed into the country, control of urge incontinence has improved. Interestingly, male babies seem to cause 84 per cent of fistulae in the first pregnancy and 64 per cent in subsequent pregnancies.

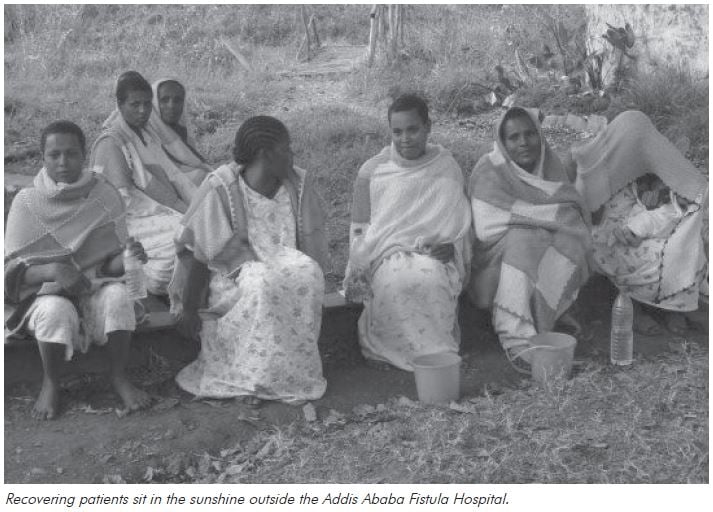

Patients stay for an average of three weeks in the 120-bed hospital. The main ward houses four rows of 12 post-operative beds with no curtains or privacy. Recovering patients, wearing hospital issue nightgowns and distinctive multicolour patchwork blankets, sit in small groups in the sunshine. There are about 97 dialects in Ethiopia making communication a challenge. Despite this, patients nurture each other with grooming and recovery.

With so many post-operative patients, I expected a significant, well-equipped operating facility. However, the one operating theatre contains four operating tables with dubious lighting and sterility. Everything is reused except syringes. Surprisingly, infection almost never occurs and there is a very low complication rate. Spinal anaesthesia is the rule and is overseen by two anaesthetists. I learned the technique as there was no dedicated anaesthetist in outreach centres. I was instructed in fistula repair and fortunately had the opportunity to do ureteric reimplantations.

Two nurses assist each surgeon and another handles the instruments. Nurse aides fetch sutures and instruments, remove bloody swabs from the buckets and manipulate the operating table in order to see the operating site. The limited available equipment is shared between operating sites. The theatre staff work tirelessly and without complaint. I was impressed by their multi-tasking.

Since AAFH commenced operating, many of the old myths have been dispelled – single layer closures and closure of the fistula and the vagina in the same direction are often the most effective.

Two teams share post-operative care and management was not necessarily by the operating surgeons. Each team consists of doctors, nurses and nurse aides. One nurse aide is dedicated to the fly swat and the hand cleanser. With nine Ethiopians on the round and with help from patients, we were able to communicate between the many dialects quite effectively.

It is sobering to recognise that these patients are the injured survivors of the ordeal of prolonged, obstructed labour and delivery of a macerated fetus. The vast majority of patients in this predicament die in the peripartum period due to haemorrhage and infection. The Ethiopian maternal mortality rate is 1:27!

A physiotherapist runs group sessions every morning, followed by specific individual instruction. In the afternoon, another group session deals with pelvic floor rehabilitation.

Urodynamics studies are done within days of being ordered using a modern donated machine. A nurse does all the tests, interprets the results and plans appropriate treatment.

The myriad of cases I experienced at AAFH were confronting and often overwhelming. A ten-year-old was accidentally shot, causing a recto-vaginal fistula. A 50-year-old presented with a vesico-vaginal fistula (VVF) she’d had for 20 years because she never knew she could have it fixed. A woman in her mid twenties presented with VVF, having spent seven years in the fetal position hoping to cure it. She had contractures of all her limbs and weighed only 27kg on arrival. She had bilateral foot drop due to ischemia of the peroneal nerves after prolonged squatting.

After almost 12 months of physiotherapy, she was able to straighten her arms and legs, but shortening of her Achilles tendons will probably have to be corrected surgically.

The majority of cases were VVF or recto-vaginal fistula (RVF) and in many cases, both. Most patients were only 18 to 20 years old, some with vaginas so scarred that they have retrograde menstruation and described endometriosis.

Many unusual problems presented. A patient presented with sloughing of the anus and rectum after using a caustic poultice prescribed by a traditional healer to treat haemorrhoids. Another patient required re-catheterisation for urinary obstruction, after bladder augmentation with a loop of bowel revealed urine which looked like thick pea soup. Infection and mucous production blocked the catheter. A 23-year-old presented who had an RVF and VVF after a stillbirth. Most of her anterior vaginal wall had sloughed off leaving a dimple where her vagina was previously. Her negligible bladder remnant resulted in incontinence, but this was not her main complaint. In Ethiopian society, she is of no use if she is unable to have intercourse or attain pregnancy. Unfortunately, the degree of scarring precluded plastic surgery or the use of prosthetics to stretch the skin.

After my two weeks training at AAFH, I spent the next four weeks with Dr Andrew Browning in Bahir Dar, north-west Ethiopia. Arriving in the dark, I found rolling anything but my ankles on the broken rock was impossible. So, carrying my bag, I negotiated the car park with some difficulty before the short trip to the hospital.

The hospital here is a government institution that services two million local inhabitants. It is spread over a vast area joined by dirt tracks. The paediatric ward comprises several small rooms with three to four beds where children are nursed by their mother. The HIV centre is a new, clean, painted building paid for by donations. Big signs advertise the clinic with no concerns about patient confidentiality or privacy.

The outpatients area consists of a large central area where patients wait on broken benches for one to three days to be seen. The perimeter is punctuated by wooden doors, each housing a different specialty. The gynaecology area, like all these clinics, is one room with a desk, a lamp and a vinyl-covered bed. There are no sheets or curtains. There are paediatric, surgical and medical clinics and a resuscitation room with a smaller desk and a bigger bed – nothing else to be seen. I hope they had everything else hidden away.

The maternity building is a concrete structure with gaps for windows. The walls are raw plaster and the tiled floors are covered in dust from the outside paths. Bleeding patients lie in the corridor on plastic covered stretchers at ground level with relatives attending to their needs.

Labour ward beds are shared by patients who move to the delivery room in the second stage of labour. Four delivery options are available – a half-bed with foot stirrups, a narrow bed, an old-fashioned birthing chair and an old arm chair. A single bar radiator is available to warm cold babies.

The Bahir Dar fistula centre is separately funded and in contrast to AAFH, there is no hand sterilising or fly swatter. Prophylactic antibiotics are used routinely and infection is rare. Here incisions are different and the dissection is not as wide. Patients are operated on early and urged to drink immediately, as intravenous fluid is expensive and limited. Catheters are removed earlier here with no ill effects. Dr Browning has developed an operation for stress incontinence which involves urethral plication and suburethral support from surrounding tissue. So far, this easily reproducible operation has a 75 per cent success rate and does not need expensive equipment, which is not available in Ethiopia anyway.

Despite my initiation at the AAFH, I was continually taken aback by confronting cases such as marriage at the age of eight, obstructed labour, a dead baby and a fistula by the age of 18, then, secondary amenorrhoea due to the trauma.

Patients in Bahir Dar receive numeracy and literacy lessons from the staff and learn enough to get by before they leave hospital. Tubal ligation is frequently requested at the time of fistula repair and it is done abdominally in Bahir Dar. After demonstrating vaginal tubal ligation, I was delighted that this became the accepted approach.

I had exposure to many different types of surgery and the opportunity to haggle with taxi drivers and explore the sights of Ethiopia. Although electricity and water are occasionally unavailable and the dial-up internet fails frequently, the overall experience is not to be missed.

The smiling faces of the patients and their appreciation for the help they are given cannot be adequately described. The interaction between the patients is wonderful to see and the effort made by the fistula centre to promote obstetric care in outlying areas will hopefully diminish the need for fistula surgery in the future.

The needs in Ethiopia are many and exposure to western advances is essential. Although few facilities are available for diagnosis and treatment, volunteering in Ethiopia gave me more than I could ever give back. I have learnt to do without many things I believed were essential and I will hopefully return on many occasions.

Leave a Reply